In its original, intended meaning, wetware is the underlying generative code for an organism, as found in the genetic material, in the biochemistry of the cells, and in the architecture of the body’s tissues.

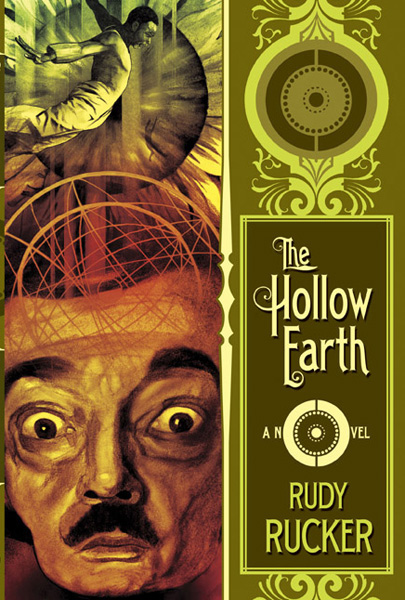

I was one of the initial popularizers of the word “wetware,” perhaps the third to use it in an SF novel, preceded by Michael Swanwick’s Vacuum Flowers and, I believe, Bruce Sterling’s Schizmatrix. I think I first saw the word in Sterling’s book.

I’m disappointed to see that over the years the meaning of the word is being watered down to mean (a) a human brain or, even worse, (b) a company’s employees.

(a) If “wetware” just meant “brain,” then we wouldn’t even need the word. The whole point of the word “wetware” is that it’s meant to make you look at the world in a new way, and to try and see biological systems from a computational standpoint. An organism is so much more than a brain.

(b) In the sense of employees, wetware might be used in a sentence like: “Yeah, we got the PCs, we got the Office software, now we just gotta hire us some wetware.” When I see people trying to reduce everything to corporate human resources issues, I think of someone giving a monkey in a zoo a crayon, and all he can draw is the bars of his own cage. But, crabbing aside, I can see the appeal to this usage for computer workers. “Why’s this keyboard all sticky?” “Wetware problem. Bill eats lunch at his desk.”

In the Mondo 2000 User’s Guide to the New Edge (Harper-Perennial, New York 1992), I defined “Wetware” as follows. (By the way, I attributed this entry to Max Yukawa, who is in fact a character in my novel Wetware. As a kind of homage, Yukawa’s physical appearance was in fact modeled on William Gibson’s, that is, Yukawa has a long, thin, and somehow flexible-seeming head. When I was starting the book, I’d sent a few pages to Gibson and he’d kindly rewritten them for me, punching them up a bit.):

“Suppose you think of an organism as being like a computer graphic that is generated from some program. Or think of an oak tree as being the output of a program that was contained inside the acorn. The genetic program is in the DNA molecule. Instead of calling it software like a computer program, w call it wetware because it’s in a biological cell where everything is wet. Your software is the abstract information pattern behind your genetic code, but your actual wetware is the physical DNA in a cell. A sperm cell is wetware with a tail, but it’s no good without an ovum’s wetware. A fertilized seed is self-contained wetware, and a plant cutting is wetware, too, as plants can reproduce as clones.”

— Rudy Rucker, R. U. Sirius, and Queen Mu, eds., The Mondo 2000 User’s Guide.

Since then, I’ve come to understand that a body’s wetware is more than just its DNA. The autocatalytic system of biochemicals in each cell is a kind of wetware itself. So the seed wetware is really the entire seed cell.

At a higher level, the arrangement of a body’s cells—and the all-important tangling of the cortical neurons—is a kind of wetware as well. The body and its high-level wetware are, of course, implicit in the low-level wetware of the original seed cell which contains the initial DNA and biochemicals. But it can be useful to regard the body as a high-level wetware system on its own, just as one might prefer looking at a program as expressed in some high-level language like Java, rather that trying to decipher it in low-level assembly language or machine code. That is, we can use “wetware” to refer to the underlying initial cell’s patterns, or to the emergent patterns of the body.

(By the way, on May 31, 2007, I made some corrections to the Wikipedia wetware entry. I hadn’t bothered to log in, and was “anonymously” there as an IP code starting with 68.)

All this sounds kind of dry and academic. But the cyberpunk novel Wetware was anything but that. I wrote it at white heat in six weeks in 1986, at the tail end of four years without a formal job—I was a freelance writer working out of a rented office in an abandoned building in the crumbling seedy core of Jerry Falwell’s Lynchburg, Virginia. This was the first of my novels to be written on a word processor—I’d gotten an Epson CPM machine with PeachText software. I didn’t know it then, but I was just about to move to Silicon Valley.

The setup for the book is that humans have built a race of robots called boppers. The boppers live on the moon, where they reproduce by building new robots in factories, often merging two boppers’ codes onto a single new body. Given that they have self-reproduction, “sex,” and mutation, they’ve evolved. But now they want to move from plastic bodies into meat bodies. They’ve figured out how to program human DNA so that a newborn baby might include some particular robot’s personality.

Humans designed the robots, and now they’re turning the tables and designing humans. The first human born with bopper code in his wetware is called Manchile. His sperm carries two tails, one with the human DNA and one with the robot-mind upgrade. He’s starting a Messianic movement on earth, mainly by sleeping with as many women as possible. Like Phil Dick’s precog mutant, the Golden Man, Manchile is irresistibly handsome. I modeled his speech patterns on those of the drummer in our short-lived Lynchburg punk rock band, The Dead Pigs.

“All the boppers really want is access. They admire the hell out of the human meatcomputer. They just want a chance to stir their info into the mix. Look at me—am I human or am I bopper? I’m made of meat, but my software is from … the Moon. Let’s all miscegenate, baby, I got two-tail sperm!”

—Rudy Rucker, Wetware.

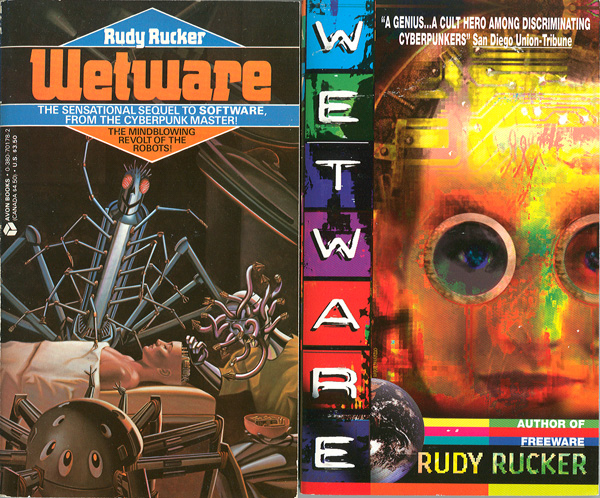

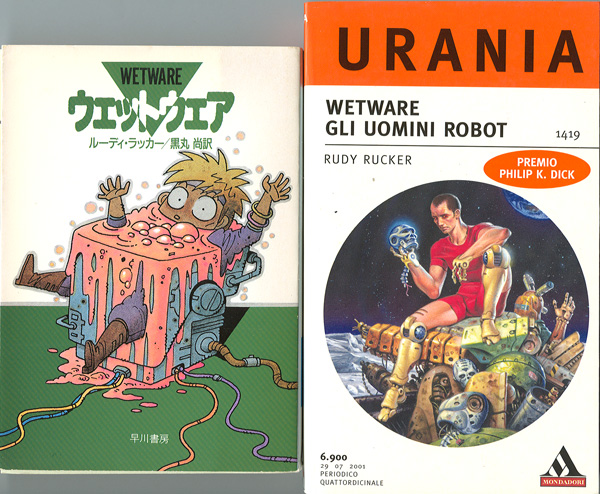

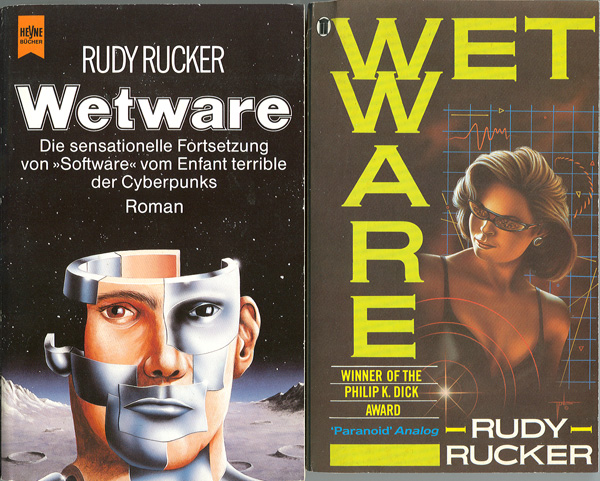

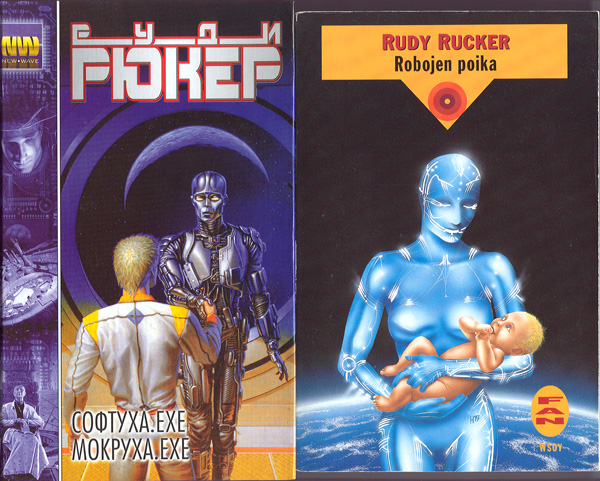

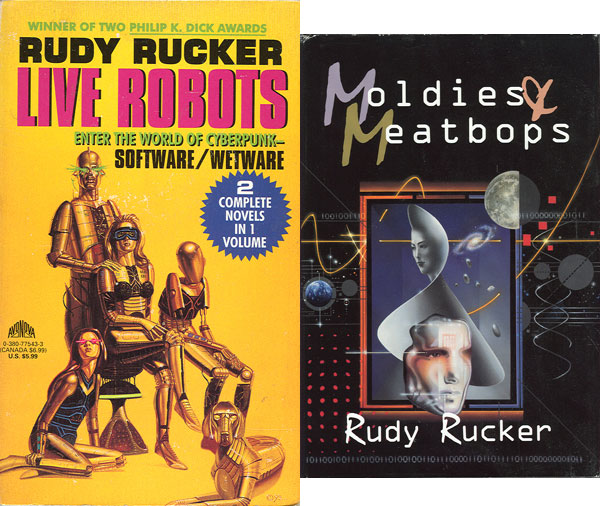

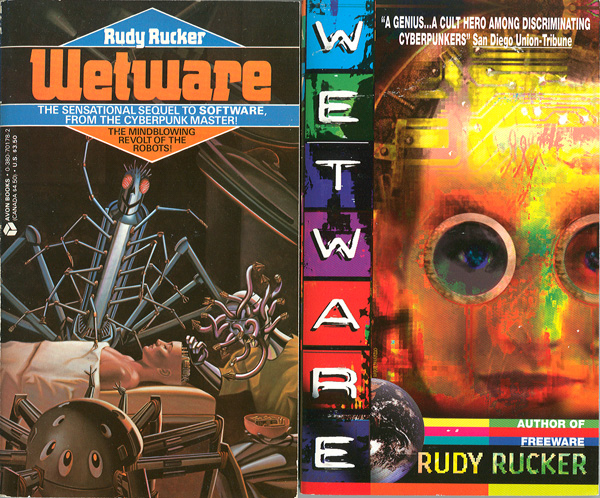

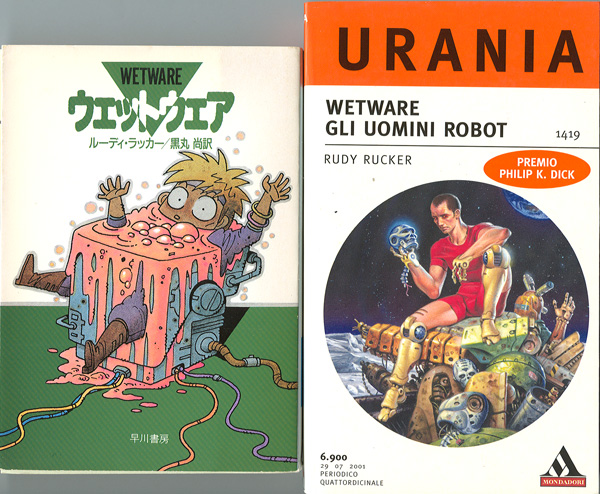

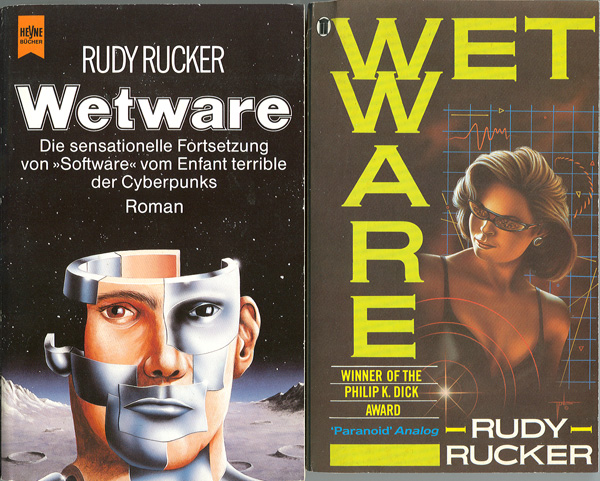

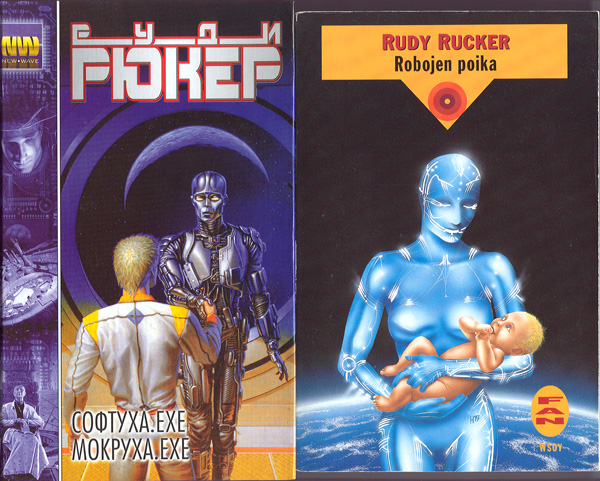

The ten Wetware cover shots above are, left to right and top to bottom, from US Avon (1988 edition), US Avon (1997 edition), Japan, Italy, Germany, the UK, Russia, Finland, Live Robots: the US Avon 1994 double edition including Software, and Moldies and Meatbops: the US Avon Science Fiction Book Club edition including Freeware as well.

Although I suggested the “Moldies and Meatbops,” title, I’ve come to regret it. For some reason I was echoing the sound of the utterly irrelevant title of “Bedknobs and Broomsticks.” I recall another (non-starter) title suggestion I’d made as well, lifted from an S. Clay Wilson one-panel cartoon: “Crazed Junkies Fight It Out With Killer Robots.” Probably just plain Wares would have been best. Note that there never was an omnibus with all four of the novels.

Added October 30, 2016.

The four-novel omnibus Ware Tetralogy appeared in 2010 from Prime Books with an intro by William Gibson. You can get it as paperback, commercial ebook, or as a free CC ebook.