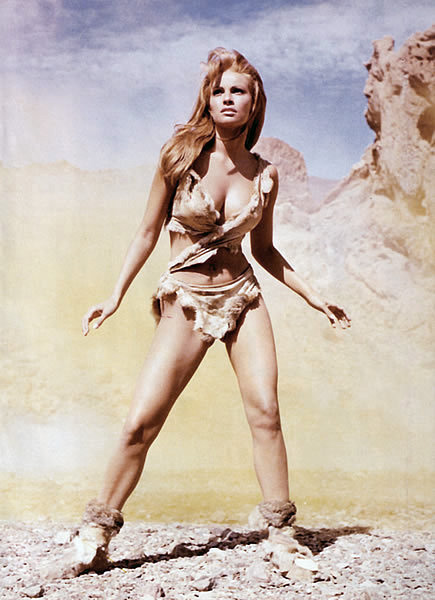

I finished a new painting today, “The Riviera.” I was going for a kind of French Impressionist look with this one, thinking of a garden party. Another inspiration was that I’d recently seen the Mel Brooks theater production of Young Frankenstein. But I went for a robot or mechanical man rather than a Frankenstein’s monster. I like how he’s glowing from the inside. In a way, this painting is an image of my wife Sylvia and me, on a car-trip we took to the Riviera with her brother Henry, in 1966, the year before Sylvia and I were married.

The Riviera, 40” by 30”, August, 2010. Oil on canvas. Click here to see larger image.

As usual, you can get prints or originals of my paintings at my paintings site, also this page has a link to my Lulu art book of paintings, Better Worlds.

I’m still fooling around with my new Alan Turing story, it’s always fun to be writing. I like the craft of the process, the kneading, the interactions with the muse.

I’ve been twittering a certain amount of late, too, and some of the tweets have to do with ramifications of my Turing research. If you want to see my tweets, click the button below.

Brendan Byrne, a young writer who edits an off-kilter webzine called “The Orphan,” sent me a link to a stirring blog post by SF titan Norman Spinrad. As sometimes happens to aging writers, Norman is having trouble getting his books published these days. Norman analyzes this in terms of a “death spiral”.

Norman is about five years older than me, he was kind to me when I was new at writing. When I was coming up, his Bug Jack Barron came as a revelation. You can put curse words in a science fiction book!

Reading his blog-post complaint, I too worry about remaining publishable. More and more often I think of the folk-tale that, among the Inuit, when a member of the tribe becomes too old and decrepit to care for, they’re put on an ice-floe with a hunk of blubber to chew as they drift northward towards the unwinking sun.

You can substitute “e-books” for “hunk of blubber,” I guess…