On Friday, Sept 26, 2008, I was part of a group reading of sex-related SF stories at the Center for Sex & Culture, 1519 Mission Street near 11th, San Francisco…it was good stuff. I read from The Sex Sphere.

Richard Kadrey read a story about spacers with hollowed out bodies and aliens living inside them, Steven Schwartz read three linked short-shorts relating to future soldiers and sex, Charlie Anders read a kind of after-school special story about a low-caste person whose “harnt” gets wet when a pilot falls for him/her on a generation starship, and Thomas Roche read a nasty freakshow tale about a woman having sex with spiders. A stronger lineup than one often hears at group readings.

On Saturday, Sept 27, 2008, at CELLspace / 2050 Bryant Street, San Francisco, I gave a keynote talk on “Sex and Science Fiction.” Both events were for Arse Elektronika , oganized by the monochrom art group of Vienna. We had a pretty good audience, and they streamed it live onto the Intenet. I had a cold, and I ached all over, so I didn’t stick around for the rest of the talks. CELLSpace has great graffittiesque murals.

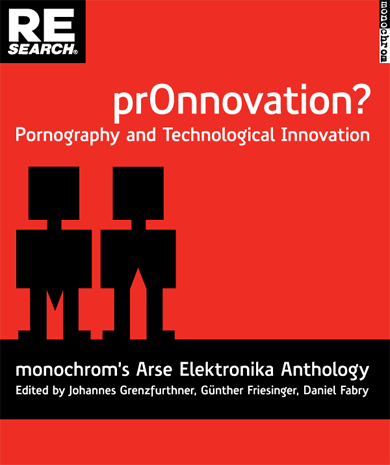

Organizer Johnannes gave me a cool advance copy of a book of the talks of last year’s monchrom conference organized—the book title is pr0nnovation? Pornography and Technological Innovation, and it is appearing under the hallowed RE/Search imprint.

You can directly access an audio of my half-hour talk as delivered, which monocrom put online as an MP3 file. I think the fileincludes about half an hour of Q&A as well. Just click on the icon below to access Rudy Rucker Podcasts.

The rest of this post is the written draft for my talk that I typed up in advance. Here we go.

“Sex and Science Fiction”

Science fiction is a mountain of metaphors, a funhouse of crooked mirrors that give us new views of our actual world.

From our genes’ point of view, we’re meat-based landcrawlers to ride around in. Imagine little double helices lounging in the hammocks of your cells. What makes us especially useful is that, now and then, we spawn off new landcrawlers with copies of the passenger genes, carrying them ever forward through time.

Putting the same point differently, if living organisms weren’t obsessed with sex, none of would be here. We’re each a link in a chain of generations, we’re dangling dollies on a slimy macramé of a trillion umbilical cords.

Of course we enjoy sex for more immediate reasons than reproduction: erotic pleasure, the orgasm, and partnership bonding. The last one is important. That’s why we talk about making love. We’re wired so that loves readily grows from the sex act.

Certainly, if reproduction were the only reason for sex, you wouldn’t be having so many orgasms. How many? Math time! Suppose you live to your eighties, and that you have seventy years of sexual activity, which makes for about 3,500 weeks. If you’re energetic enough to average three pops a week for seventy years, you’re talking about something on the order of ten thousand orgasms. All that brain-flashing to bring forth at most a couple of kids! “Oooo Mommy, you mean you and Daddy did that twice?”

So how about science fiction and sex? Where have we been, where are we headed, and how much further can we go?

One sex story I always think of is Samuel Delany’s, “Aye and Gomorrah,” about a cadre of spacers who’ve been surgically altered so that their crotches are as featureless as those of a plastic Barbie doll’s. Why? Given the amount of mutating radiation that these astronauts absorb in their space-stations, it would be too dangerous to allow them to reproduce. In the story, there are people who are sexually obsessed with the Barbie-smooth spacers. These fetishists are called frelks—a great word.

In this context, I also think of a particular story about people being sexually attracted to aliens, “And I Awoke and Found Me Here On The Cold Hill’s Side,” written by Alice Sheldon, under her nom de plume James Tiptree, Jr. Upon seeing aliens, the story’s characters have a surprising and overwhelming sense of lust. Kind of like how some of us may react to our first sight of a gay pride parade! Ah, those six-foot-tall honking-loud brides…

One reason we’re attracted to sex with other people is simply because they’re different. Gender isn’t necessarily an issue. That’s the core idea in both the Delany and the Sheldon stories: otherness is a turn-on. And any other person is, for all practical purposes, an alien, if you really think about it.

Note that it’s not just the difference that turns us on, it’s the idea that there’s an intelligent mind inside the different body. Another mind that mirrors you, a mind you can in fact pair up with for an endless regress of mutual reflections.

There’s a major difference between sex with a person and sex via media. In sex with a person, you’re talking about emotion, the positions of your limbs, touch across large skin areas—about tastes, scents and pheromones. A candle by the bed is nice, but you can just as easily make love in the dark.

In media-based sex, we’re reduced to visual images, perhaps enhanced by recorded sounds. But there’s no emotion, touch, tastes, or smells. And text-based sex is even more abstract.

I’m a little sorry to see the decline of text-based pornography. It used to be in every corner store, and now you hardly see it—although it can be found online. In the 1970s, I had a bar-fly friend who was paid by the hour to write porno novels in an office in downtown Rochester, New York. I thought he was cool. A real writer!

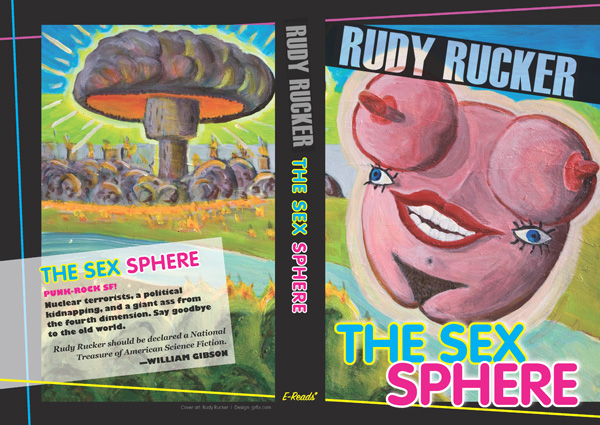

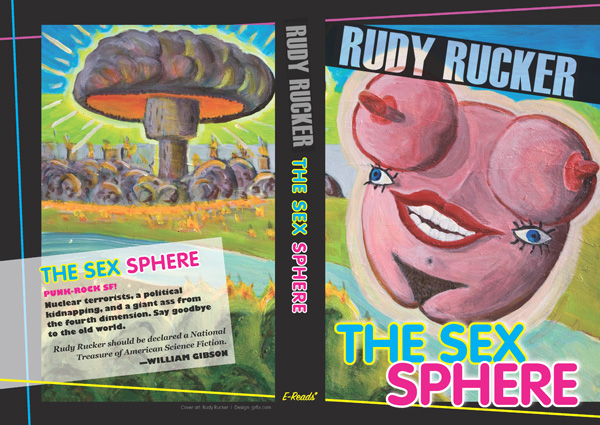

Still on the theme of sex with aliens, my novel The Sex Sphere features a giant ass from the fourth dimension. She’s called Babs. She has eyes, breasts, a mouth, a vagina—but no limbs. She can fly, she’s into nuclear terrorism, and her ultimate goal is to utterly destroy our universe. Have any of you ever dated her? The book’s being reissued by E-Reads this fall.

One of the earliest bizarre SF sex stories that I read was in Philip Jose Farmer’s 1950s anthology, Strange Relations. I’m thinking of his story, “Mother” in which a stranded space-explorer finds shelter within a cavity in a meaty plant. The plant—or perhaps its an animal—feeds him food and bourbon, nursing him along. And it turns out that the astronaut is expected to attack a certain area of the plant’s womb, which will catalyze her into a pregnancy, enabling her to bear young. And after his attack the mother-plant will eat him. In a way, it’s an incest story, but looked at differently, it’s also a story about retreating into a cocoon.

Think of a person alone with their computer—whether they’re viewing internet porn, having sex-talks in chat-rooms, or playing erotic roles in a multiple-user videogames. Or think of people lying in Matrix-style jelly-pods with their brains plugged into a group virtual reality.

I find these scenarios sad. In “Mother,” the character at least has the ability to fecundate the surrounding blob—but what can you as an individual do to the internet? What can you do to some vast virtual reality that you’re duped into spending all your time with?

Well, in the case of the internet, at least you can post comments, upload videos, start a photostream, run a blog. And maybe, if you’re lucky, you can galvanize another human into meeting you face to face.

It’s always important to remember that computers are dead and boring compared to our fellow humans. Even if there’s a human on the other side of the computer output that you’re interacting with, the machine is still between you, even more isolating than—you should pardon the expression—glory-holed toilet-stall wall.

For a little while, people were talking about having sex via the internet by means of computer-operated sex toys. It’s doable, but who wants to bother? It’s the skin that matters, the breath, the eyes, the voice.

As a partial improvement, in my novel, Freeware, I had sex toys that were made of flexible and intelligent plastic that could move on its own. I called the material “piezoplastic,” and it had become rather intelligent due to a wetware mold infestation. Bigger chunks of the fungus-dosed piezoplastic were autonomous and vicious beings called moldies—and those who loved them were known as cheeseballs. Moldies would take control of a cheeseball by inserting a small slug of their plastic into the human’s skull, and the sluggie would run the person like a robot remote. You might call this an objective-correlative for sexual obsession.

As an SF writer, I wonder if there could be a non-plastic and purely biological medium for enjoyable remote sex. Certainly a sex-toy would be more congenial if it were made of a human tissue culture instead of plastic. Ideally the seed cells for the tissues would come from your lover’s body, so that the smells and pheromones are just right. Actually, Bruce Sterling and I wrote a story called “Junk DNA” in which these little jobbies were called Pumptis.

Of course, for full satisfaction, the personal-intelligence touch is needed. You want a way to project your mind into that remote Pumpti that your darling is going to use—and vice-versa. Well, we can do that via quantum entanglement, no prob. Everything’s easy in science fiction.

While your partner is getting it on with your Pumpti, you’ll be diddling the Pumpti that he or she gave you. And, even better, you’ll projecting your consciousness into the remote Pumpti and into your partner’s mind as well.

Great. But, wait—this doesn’t sound all that different from phone sex…or an exchange of—do you remember?—love-letters.

Basically, remote sex is boring. There’s no substitute for face-to-face. Let me say a little about possible SFictional amplifications for in-person encounters. For instance in my Ware novels, there’s this drug called merge. Lovers get into a bathtub called a love puddle, they splash on the merge, and their bodies melt and flow together—making a happy glob of flesh with four eyes on top. After an hour or so, the merge wears off, and the couples’ body shapes return.

I like to think of telepathy as a sexual enhancer. I already mentioned that it’s exciting to have your own mind mirrored in someone else’s, even as you’re mirroring then and so on forever. Suppose that the mirroring is though a direct brain contact. It’s easy to suppose that the feedback could flip into a chaotic mode, generating fractal strange attractors. It would take a bit of delicate maneuvering to avoid spiraling into the fixed-point attractor of a brain seizure.

Here’s a longer passage about this, mashed up from my novels Saucer Wisdom and Hylozoic.

So now Larky and Lucy can see through each other’s eyes, but then Larky glances over at Lucy and she looks at him and they get into a feedback loop of mutually regressing awareness that becomes increasingly unpleasant. It’s kind of like the way if you stare at someone and they stare back at you, then you can read what they think of you in their face, and they can read your reaction to that, and you can read their reaction to your reaction, and so on. It gets more and more intense and pretty soon you can’t stand it and you look away.

But with a direct brainwave hookup, the feedback is way stronger. In fact it’s like what happens when your point a video camera at a TV monitoring what the camera sees. Lucy’s view of Larky’s face forms in Larky’s mind, gets overlaid with Larky’s view of Lucy and bounced back to Lucy, and then it bounces back to Larky, bounce bounce bounce back and forth twisting into ragged squeals.

Some couples become addicted to the dangerous intensity of skirting around the white hole of feedback, of bopping around right on the fractal edges of over-amplification, on the verge of tobogganing towards the point-attractor of a cerebral seizure. Fortunately you could always shut off your telepathy. With practice, Larky and Lucy had learned to skate around the singular zones, enjoying the bright, ragged layers of feedback.

Coming back to the concept of sex as reproduction—what if you were engendering something more than a child? In a couple of my novels, I’ve had couples who somehow save our universe as a side-effect of their love-making. Father Sky and Mother Earth. It’s an old legend that expresses something fundamental: sex as creation.

Here’s a version of this from Spacetime Donuts.

He was floating, a pattern of possibilities in an endless sea of particulars.

“Be the sea and see me be,” the words formed…somewhere.

He let his shape loosen and drift to touch every part of the sea around him, a peaceful ocean like a bay at slack-tide on a moonless summer night…peaceful, while in the depths desperate lives played out in all the ways there are. Taken all together, the lives added up to a messageless phosphorescence, a white glow of every frequency.

“And are you here?”

“As long as you are.”

“Can we go further?”

NOW

And there’s a scene like this in Postsingular.

They undressed and began making love. They had all the time in the world. Everything was going to be all right. At least that’s what Jayjay kept telling himself. And somehow he believed it. He and Thuy were one flesh, all their thoughts upon their skins. Their bodies made a sweet suck and push. The answer was before them like a triangular window.

Jayjay had been too tense and rushed to teep the harp before. But now—now he could feel the harp’s mind. She was a higher order of being, incalculably old and strange. She knew the Lost Chord. She was ready to teach it to him. Jayjay and Thuy melted into their climax, they kissed and cuddled. Jayjay got up naked and fingered the harp’s strings. They didn’t hurt his fingers one bit.

The soft notes layered upon each other like sheets of water on a beach with breaking waves. Guided by the harp, Jayjay plinked in a few additions, thus and so. And, yes, there it was, the Lost Chord. Space twitched like a sprouting seed.

And with that, the harp was gone.

No matter. The sound of the Lost Chord continued unabated, building on itself like a chain reaction, vibrating the space around them. Jayjay smiled at Thuy. He had a sense of endlessly opening vistas.

“You did it,” said Thuy. “You’re wonderful.” She wasn’t talking out loud. Her warm voice was inside his head. True telepathy. Jayjay had unrolled the eighth dimension. He and Thuy had saved the world.

Sex is everything.