For whatever reason, most people don’t think of William Burroughs’s novel Naked Lunch as science-fiction, but really it is. In particular, it’s what I call Transreal SF, that is, a form of autobiography in which one’s experiences are made more vivid by transmuting them into SFictional tropes, see for instance my talk, “Power Chords, Thought Experiments, Transrealism, and Monomyths.”

[Hummingbird and Orchid by Martin Johnson Heade.]

Burroughs himself often wrote admiringly about SF in his letters, and said that’s what he was indeed writing. But people ignore this. Perhaps it’s that so few SF works aspire to such a high literary level, or that Naked Lunch doesn’t have a straight-through plot-line. But if you look at the tropes in the book, it really is SF¬—aliens, imaginary drugs, telepathy, talking objects … the gang’s all here.

I’m thinking about the book both because Burroughs is a character in my novel-in-progress Turing & Burroughs, and because I watched David Cronenberg’s Naked Lunch via NetFlix instant-watch last night.

What great cinematography—the framing, the colors, the segues, the simple but telling effects. The acting is great too, it’s understated, which is important—it’s easy to go over into gauche, hammy stuff when portraying legendary figures like the Beats. Judy Davis is a wonder as Joan Vollmer (called Joan Rohnert in the film), and as Jane Bowles, also called Joan in the film.

And what a wonderful script. Cronenberg himself has the credit for the screenplay. You can find it online, transcribed from the movie by some fanatic, at Drew’s Script-o-Rama. The novel Naked Lunch doesn’t have a single clear plot-line that would make a movie—indeed the lack of such a plot is a key artistic element of the book, and a key aspect of the mythos around the book.

For the purposes of the film, Cronenberg created what Wikipedia terms a “metatexual adaptation.” That is, he blended elements of the novel with the by-now-legendary story of Burroughs’s life—the shooting of his wife, the expatriate years in Tangier, typing the pages of Naked Lunch high in his Tangier room, Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg helping him assemble the manuscript. All of this material is outlined in Burroughs’s letters, and in the reminiscences of his Beat friends—the transreal oeuvre is blended together to produce the transreal film.

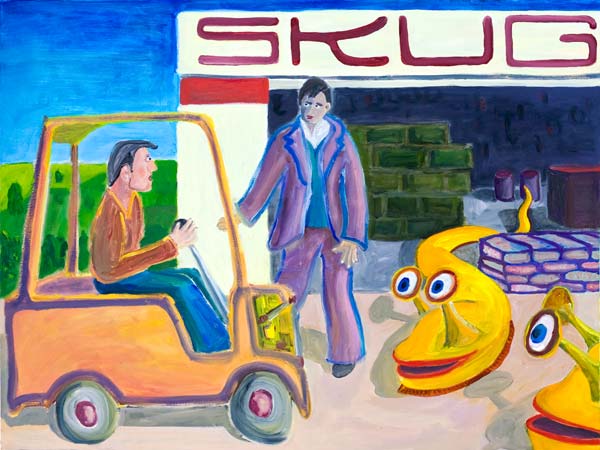

It’s a brilliant move on Cronenberg’s part to have the typewriters be alien beings. For a writer in those pre-computer days, a typewriter was an object of great mana. A partner, a friend, a tool—more reliable than any computer ever is. I remember in 1982 going on a trip with nothing in my suitcase but underwear, my pink IBM Selectric typewriter and some Clash and Ramones records. And to have these machines become talking insects or alien heads is a great concept.

Cronenberg made two marketing moves to enhance the film’s general appeal.

First of all, rather than having the main character be addicted to opiates, the Bill Lee of the movie is addicted to not-quite-real substances like cockroach-extermination-powder and the powder of the “black meat,” taken from very large fresh-water Brazilian centipedes. Burroughs himself used this move in the novel—rather than going on and on about heroin as he’d done in Junkie, which is a turn-off for many readers. In Naked Lunch , the characters are obsessed with these more science-fictional drugs.

The second market-friendly move by Cronenberg—which aroused the ire of some—is that he plays down his Bill Lee character’s homosexuality. To some extent this fits with the Burroughs of the early 1950s. Bill was, after all, married for a time—before he shot his wife. And, judging from his letters, he was always put off by overly flamboyant flaunting of one’s homosexuality. One gathers from Burroughs’s work that there there was a definite transition period for him in the early 1950s, and Cronenberg sets his character in the period of the transition.

By time Burroughs was actually living in Tangier, he was well past the transition, constantly writing about boys in his letters, so in that sense the film is historically inaccurate. But we’re not talking about true history in the movie Naked Lunch . We’re talking about attaching the images and dialog of an author’s fantastic novel to a mythologized version of the author’s life. And in some ways the transitional state is a good choice to use for the film. In any case the character is, as Burroughs remarked to Cronenberg re. the film, “queer enough.”

I did find the ending of the movie a downer, to have Bill repeating the same dreadful mistake that he’d made near the start. Cronenberg is taking off on a possibly ill-advised remark by Burroughs to the effect that if he hadn’t shot Joan he might not have become a writer. That’s not a place that most of us want to go.

For my taste, it always a little cheap and obvious to give a novel or a movie a serious feel by using a hard, downbeat climax. What’s the line? “Tragedy is easy, comedy is hard.”

One of my favorite bits in the film is when the Burroughs character is talking to the Paul Bowles character, and the older man is telling Bill all these shocking intimate things about himself, and Bill says, “I’m surprised you’re telling me all this,” and Bowles says, “Well, I’m not saying it out loud. The conversation you’re hearing is telepathic. You see, if you look closely, the words you’re hearing don’t match the motions of my lips.”

Another great bit is when Bill is passed out on the beach with, he thinks, his broken typewriter in a gunny-sack. And Jack and Allen show up to cheer him up. And Bill mumbles, “A little trouble with my typewriter.” And the boys look in the sack, and all that’s in there is trash—empty pill bottles and cans and bottles. “My typewriter.”