I got to know Jaron Lanier a little bit in the 1990s, when Virtual Reality was becoming a craze. Jaron was one of the very first people to talk about VR—see his April, 2001, Scientific American article, “Virtually There.” By the mid 1990s, his company VPL Research was making one of the first “Data Glove” devices, and the Advanced Technology group at Autodesk was using these gloves for their so-called Cyberspace project.

I was working at Autodesk at this time, writing some demos for the Cyberspace platform, so I’d see Jaron from time to time, and I found him very interesting. Once he remarked that his motivation for working on VR was because he dreamed of having a really good air-guitar, one which could in fact morph into arbitrary instruments. And then, being Jaron, he went ahead and made an album this way, The Sound of One Hand. And here, on the same theme is a link with some playable tracks from his latest album, “Proof of Consciousness“.

In person, Jaron makes an odd impression. Like other programmers and mathematicians I’ve known, he incorporates a mix of being very well-informed about certain things, while being unaware of some topics that the average human might know. And—extra wild card—he’s a musician as well.

In the last section of his latest book Jaron hints that he seems odd because he’s an alien cephalopod—“More than one student has pointed out that with my hair as it is, I am looking more and more like a cephalopod as time goes by.” The truth is coming out! But maybe I’m overinterpreting! I do love cuttlefish a lot…I pretty much try and work one into every novel that I write…

The book I’m talking about is You Are Not a Gadget. He’s trying to put his finger on some things that might keep the Web from being as wonderful as we’d like it to be. Cephalopod or not, Jaron does a good job of promoting his work, see his recent interview on “The Wisdom of the Hive” in Scientific American, and many more pages and links on his book site.

One point Jaron makes is that group-written sites like Wikipedia aren’t necessarily as good as we think they are. I gather that he was in part drawn into making this critique by some problems he had with his own entry in Wikipedia. I know this feeling—it’s frustrating if anonymous strangers post “official reference information” about you which strike you as factually incorrect. Personal issues aside, you’ll notice that if you read a Wikipedia entry on some topic about which you’re very well-informed, you’ll often find that the posted information includes subtle errors and biases. In principle, you set about trying to correct the entries, but at some point this becomes a waste of energy. If you’re truly an expert on something, it’s more satisfying to make your own independent web page about it.

Jaron argues that the very anonymity of the Wikipedia contributors can serve to conceal the contexts from which their speaking. He makes the point that, if you take the time, you can often find better, more grounded information by looking a little further down into the list of hits that Google returns when you search for a topic. Even so, for casual use, it really is very pleasant to have Wikipedia around, with the information being presented in an encyclopedia’s uniform format.

But a lot of crowd-sourced pages really seem like crap, cf. the growing number of Web 2.0 “answer” sites, where people post answers to questions, and other people vote on which answers they like best. Ask any question in the Google search bar and you’ll see five or more sites like this. It’s like, “We want an advice website, but we’re not going to pay anyone to write the advice, we’ll let it emerge, and we’ll make money from ads.” Sometimes this works, but often it doesn’t. My guess is that the wiki format, in which people can revise each other’s posts is more likely to converge on something useful—with the caveat that you then have the anonymity and lack of context.

You can preview some of Jaron’s thoughts on crowd-thought in his essay, “Digital Maoism: The Hazards of the New Online Collectivism.”

I’ll mention one other issue that Jaron raises—a topic that hits very close to home for an author or a musician. It’s really not sustainable to expect for people to be able to read and hear everything out there for free. Some have argued that, even if you give away your creative work on the Web, you can still earn money by value-added activities like selling T-shirts or making personal appearances.

But if you’re a creative type, you don’t necessarily want to be rushing around trying to scrounge up small-money deals. It’s too much like panhandling, or having to “sing for your supper” as Jaron puts it. You’d like to be able to create something in undisturbed privacy, put it out there, and gradually get remunerated as people access your work.

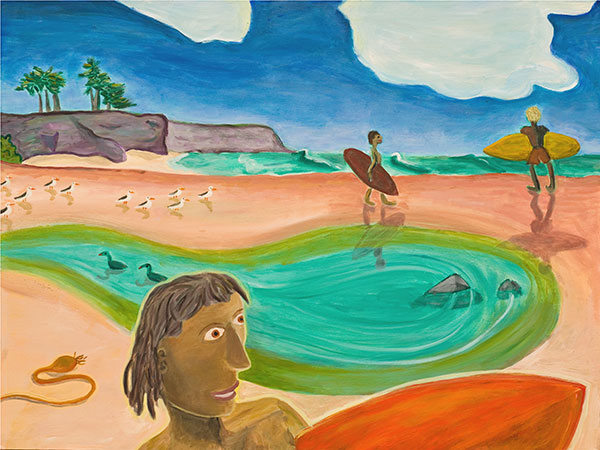

A very few authors and musicians do give away their work online and do fine with their careers. In SF circles, Corey Doctorow is the canonical example of someone who gives away electronic versions of his work while managing to sell plenty of paper copies. I myself have toyed with this approach, putting my novel Postsingular up for free download at the same time that it appeared in paper. In my case, I didn’t see this as significantly helping or hurting the sales of the book, although possibly it hurt sales a bit, or maybe it did help, as Hylozoic, which wasn’t posted for free download, sold a bit less. Writers want to be read, so at some level we do like giving away electronic books, and I probably would have given Hylozoic away as well, but my publisher didn’t want me to do it, they had some hopes of making money with Kindle and ebook sales.

It’s always hard to tell about these things, because we only get to live in one universe. At this point, there’s still very very little money in ebook sales for people other than, say, Stephen King or authors of (The)+(Proper noun)+(Noun) books, so the issue of free electronic books is somewhat moot. But now, as the ebook market keeps edging towards picking up, I think many writers and publishers feel more resistance about giving away their electronic books for free. The situation is different for musicians as the preferred form for music distribution is now electronic. The dilemma comes up for artists, too—some of us like to sell prints of our works online, and for that reason we don’t make hi-res images of our work freely availalble.

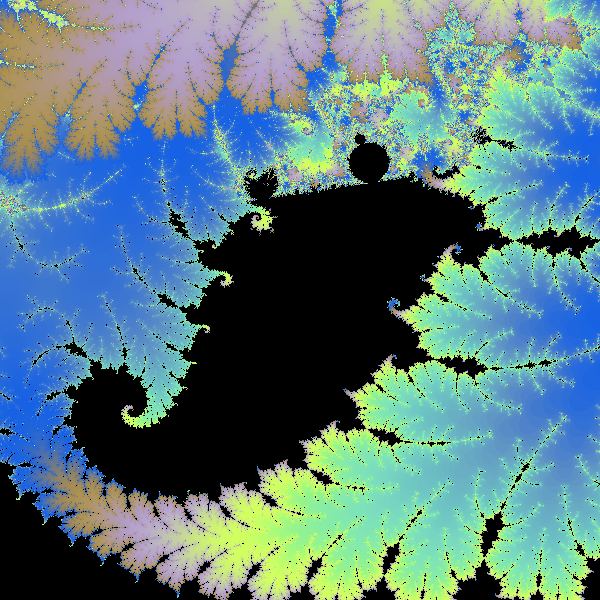

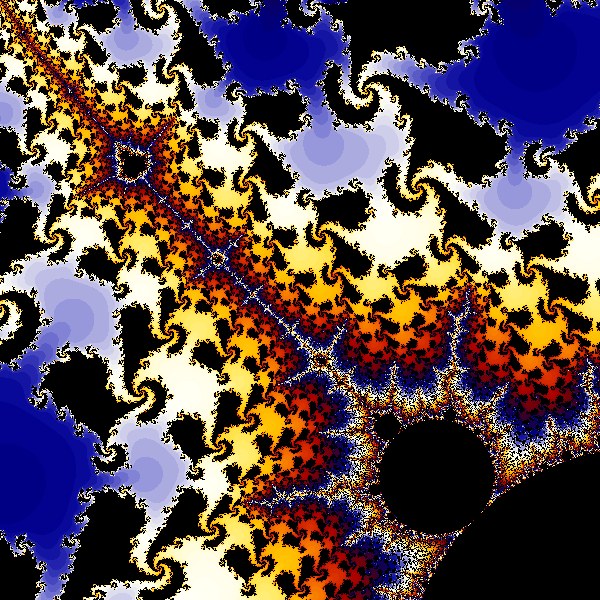

[MandelQuinticMosquitoes, detail of a quintic Mandelbrot Set.]

Jaron advocates a very nice solution to the problem that was proposed by Ted Nelson many years ago: this is that there be, in effect, only “one” copy of each artistic creation on the Web, and that whenever anyone access this copy, their browser automatically makes a smallish micropayment to the author. In practice there wouldn’t literally be only one copy of, say, a photo, a song, or a book—but it would be possible to make the system seem to behave as if this were in fact the case.

As things now stand, artists now seem fated to be selling our out-of-print or more obscure creations through things like Google Books or iTunes. These “Lords of the Cloud” (as Jaron calls them) collect the viewing fees and the revenue from sidebar ads and pass on whatever cut they deem reasonable to the actual authors. But why do we need Lords of the Cloud? An iron-clad, possibly government-backed, micropayment system would be cleaner, more open, and more fair.

Though maybe we don’t want the government, per se, involved. But, as Jaron also points out, it’s kind of crappy the way that the main, inviolable thing on so many web pages is ADs, ever more personalized, ever more intrusive and easy-to-mistake-for-something-real.

One more remark about cephalopods like octopi and cuttlefish. Jaron argues that their brains might in fact be comparable to ours, but they don’t get to have a childhood during which their elders teach them things. The edge that they do have is that, with their intensely variable skins, they are in some sense born masters of virtual reality. Jaron encapsulates these thoughts in an equation:

Cephalopods + Childhood = Humans + Virtual Reality.

Or, to quote the title of the great Talking Heads movie: “Stop Making Sense.” You go, Jaron! Lead the fight against bland consensus reality.