I haven’t been in a condition to write any fresh blog posts this month, but I should be better soon. In the meantime, just to keep the blog alive, I’m posting an excerpt from my novel-in-progress, Turing & Burroughs, which features William Burroughs and Alan Turing in a relationship.

In the following passage, Burroughs describes a 1955 scene where he returns with Alan and their friend Judy Green to the room in the Bounty Bar in Mexico City where Bill shot his wife Joan Vollmer in 1951. He hopes to come to terms with Joan’s ghost. Bill, Alan, and Judy are all “skuggers,” that is telepthic, shape-shifting mutants hosting a parasitic slug-like being called a skug. Judy is an early electronic musician, who creates a kind of artificial sound she calls acousmatics.

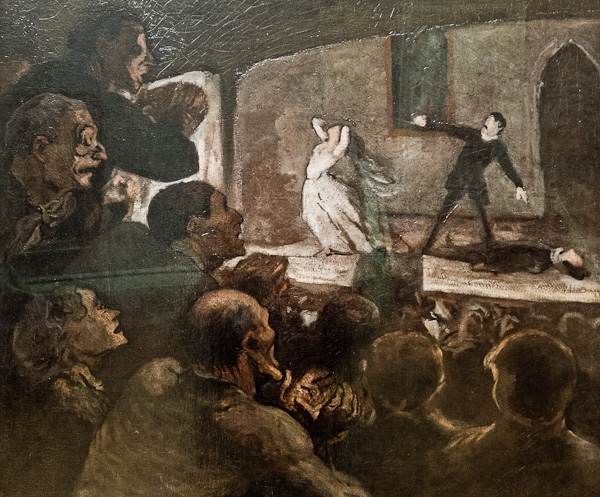

The illos for this post are random images that have accumulated in my to-blog folder.

[Begin excerpt of draft for Turing & Burroughs.]

We were nearing the all-night market that we’d passed on the way to the graveyard. Alan trotted over to one of the butchers there and—how horrible—purchased a hundred-pound skinned calf, draping the creature across his shoulders. Uncut protein for Joan.

I’d asked the Bounty bartender for any old room. But—I could hear the unerring ping of synchronicity—he’d given us the very room in which I’d shot Joan in 1951.

The room had become a short-term spot for whores and johns. Where once the lodging had held books, rugs, and a circle of friends, it was now reduced to a bed, a chair, a light bulb, a glass by the sink. Alan threw the slaughtered veal calf onto the dirty floor. A church bell tolled midnight. I closed the door. The intense silence peculiar to Mexico engulfed us—a vibrating, soundless hum.

I spawned a skug off my stomach and laid it upon the veal calf. The bony flesh shuddered and took on life, forming itself into a featureless loaf. I laid Joan’s finger atop the swollen, pulsing pillow—I was like a bishop installing a saint’s bone.

Judy Green sang to the skug, running her odd voice up and down some archaic scale, and vibrating her skin to add dark, low overtones. Guided by the finger’s DNA, and by my teeped hints, the skug morphed into a crude human form, tightened into something like a window-dresser’s mannequin, then locked into a replica of Joan’s final, spindly form. A golem.

I set to work on programming the thing’s mind via teep, reconstructing Joan’s personality from my memories. I remembered the early days—camping on Joan’s vaguely oriental bed with coffee and benzedrine, chattering about decadence and nothingness, Joan alluring in her silks and bandannas. I thought of Joan catching a June bug outside our shack in Louisiana, and tying a thread to the bumbling bug’s foot—Joan called it the beetle’s hoof. She flew it in a circle around our heads. Even in Mexico City, Joan kept her slant humor, seeing the adventure in the squalor, making herself at ease on a pile of six mattresses, calling herself the princess and the pea. A phrase from Allen’s memoriam poem popped into my mind. “She studied me with / clear eyes and downcast smile, her / face restored to a fine beauty.” And now it was so.

Joan’s body sat up and blinked, very jerky, very robotic. This wasn’t going to work. But now I saw the glinting ultraviolet cuttlefish of Joan’s ghost. She was dawdling at the fringes of visibility, twiddling her tentacles and flipping her hula-skirt fin, making up her mind. And now she dove into the skug.

Still sitting on the floor, the Joan-thing shuddered like a wind-riffled pond. She fixed me with her eyes and began talking, her voice languid and intermittent, like music down a windy street.

“I want to leave. I want to go to paradise. But I’m not done with you, Bill.”

“I’m agonized by regret,” I said. “I writhe abjectly. Go up to heaven, Joan. You deserve it. Forgive me and go.”

“What about little Billy?” asked Joan, rising lithe to her feet. She seemed taller than I remembered. Reaching out, she laid a cool hand on my face.

Immediately I had a physical sense that I was carrying a large covered basket. I’d been carrying it in my arms for a long time. Our son Billy was in the basket. He was going to die.

“I’ll help him!” I cried. “It won’t happen that way.” I stepped back, breaking Joan’s hallucinatory contact.

“You won’t save him,” said Joan, bleakly mournful. “I know you.” She looked around as if only now recognizing this as the spot where I’d shot her.

I stood frozen in place, awaiting her next move, more than ever wishing I hadn’t set this in motion.

“Ooooo,” said Joan, her voice purring up through an octave. “I know. It’s time for our William Tell routine.”

Without moving her arms or her shoulders, she poked her head out on a snaky tendril, scanning the room. Of course she spotted Judy Green’s gun.

“No,” said Judy, guessing what lay ahead. It was like we were playing out a script. Joan held out her hand. In thrall, Judy passed her the pistol. Turing sat goggling like a mute imbecile.

“The glass, Bill,” said Joan, her voice low and firm.

I moved across the room like a fish in heavy water. I set the glass on my head.

A few paces away from me, Joan raised the pistol.

“Don’t,” I said, faint and husky. “Don’t shoot me, Joan.”

She fired. I flinched to the side. The bullet struck my temple. I slumped to the floor: deaf, blind, undead. I could still sense things via teep.

“It’s over!” breathing Joan, with a fading lilt of summer in her voice.

Her ghost wriggled from her skugly flesh and fluttered in the air. Like a dragonfly now, not a cuttlefish. Flying around the borders of my teep, she shrank as if moving far away. Joan’s spurned new body reverted to being a skug. It raised one end, as if sniffing the air, then humped along the floor and out the window.

Brain-scrambled as I was, I hallucinated that I humped my own body after Joan’s skug. Fully into the invisible zone of the astral plane, I slithered out the window and—just for jolly—levitated myself fifty feet high in the air. See me fly?

La policia kicked in our rented room’s door, inevitable as stink on shit. It was like a straight-on replay of 1951, but with me in a new role. As the victim, I lay naked on a marble slab with a spongy erection. Cops all around.

“We need acousmatics,” said Judy. “I memorized the sounds of a race riot in Miami. I’ll pump the replay from my skin, mixing in the shrieks of swine at the slaughterhouse. We’ll raise Bill and rectify those policia pronto.”

My head was splitting in unbearable pain. I retracted my limbs, blanking things out.

“Bill?” said Alan, leaning over me and shaking me. “Bill?”

We were still in the room where I’d been shot. I sat up and spit the bullet from my mouth. The sun was high.

“What a burn,” I said. “Let’s split this scene.”

“Agents everywhere,” said Judy, leaning out the open window. “Like flies on meat. We need more acousmatics.” She emitted a fresh torrent of noise. It was a collage of every sound I’d ever heard in my life—thrown into a rock-tumbler.

The sky went pale green. Hailstones fell past, big as hens’ eggs, shattering on the street. Elephants trumpeted frantic at the drone of an approaching twister. The street-side wall rocked twice and exploded out. Turing and I slid helpless across the floor, pissing our pants. Cars flew through the air with clown-cops behind the wheels. A striped circus tent swept upwards, drawing me into a whirling shattered midway of bleachers and shooting galleries, of sugar skulls and Socco Chico queens…

Poised at the virtual tent-peak of the vortex was Joan, far and wee, the bride on the funeral cake, luminous white, bidding farewell, giving me the finger. Behind her glowed the divine light of a heavenly Missouri sunset.

Cut. I was still in that room we’d rented, lying on the floor in a clotted crust of blood. I’d been here all night, reflexively regrowing my brain. The sunlight lay like pig iron on the ground. The police had dispersed—if they’d ever been there at all.

[End excerpt of draft forTuring & Burroughs]