Talk by Rudy Rucker for the Bridges conference on Art and Mathematics at Aalto University, Helsinki, 11am, August 1, 2022. Many thanks to the organizers for inviting me, particularly George Hart, Kirsi Peltonen, and Eve Torrence. For more on my art see my Paintings page. For more of my thoughts, see my books, including my volume The Lifebox, the Seashell and the Soul, and my autobiography Nested Scrolls. For examples of my novels, try The Ware Tetralogy or the recent Juicy Ghosts, which features a character named Anselm, in memory of my distinguished Finnish poet friend Anselm Hollo.

As of August 3, 2022, my podcast audio of the talk is available.

Alternately, you can play a video of the talk on YouTube, and the video includes the slides.

White Light

As a boy, one of the mathematical notions that interested me the most was infinity. Lying in bed, I’d imagine falling down a well-lit shaft, like Alice on the way to Wonderland. There were balconies on the walls, with friendly men, attractive women, and cute aliens waving to me. I’d keep falling and watching for quite a long time.

I write a long scene like this in my 1987 novel The Hollow Earth. In my novel, my hero and his companions are falling through a 2000-mile-long hole that runs through the outer crust of our Earth, which is indeed hollow, like a tennis ball, with a big empty space in the center. And I did an early painting of the Hollow Earth, and it’s not very good, but itt helped me see the scene in my head. Math art can be a tool for visualization.

Here’s a different Hollow Earth painting, done twenty years later, and I like it better. We’re inside the hollow Earth, near the center, and here’s a giant flying shrig, who is a mix of a shrimp and a pig. My wife says the shrig’s face is my self-portrait.

Those odd things floating near the shrig are what I call krakens. I discovered the krakens in the process of doing mathematical research into higher-order Mandelbrot sets—and I discovered a cool fractal which I modestly named the Rudy set. Sometimes my math feeds into my painting as well as into my writing.

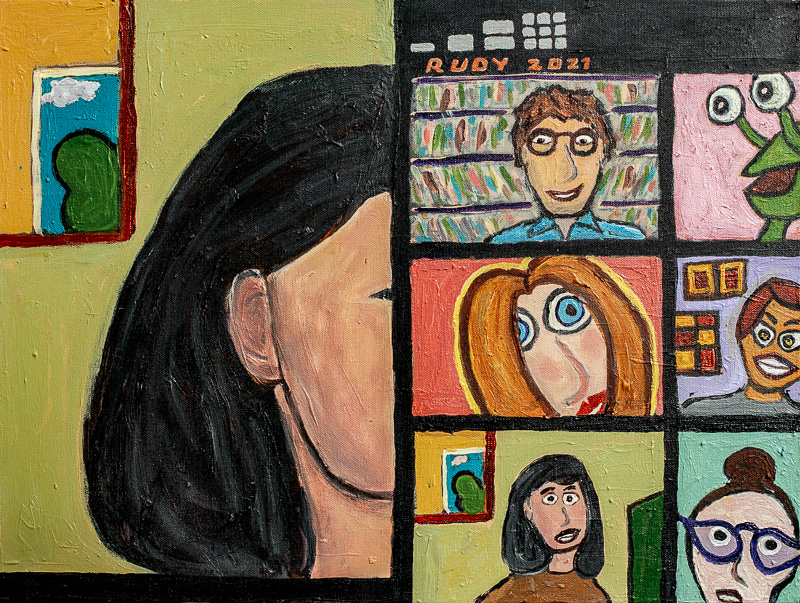

What is it like to write a novel? I like to say it’s like dreaming while I’m awake. I get into the zone, and then I write down what I see and what I hear in my dream. The dream flows out of my planning and my subconscious and from some ineffable force that I call the Muse.

Painting is a little that way too. As in writing, there’s a feedback between the work and your thoughts. The book draft and the painting canvas help you. You put something down, and look at it and see what it reminds you of. Not in a logical way, but in an intuitive way.

Again, think of the Muse. The Muse is a real thing, not a joke or a poetic fantasy. Part of writing or painting is waiting for the Muse to show up. You invite her in by staying sharp and working on the project.

Here’s another painting that relates to that tunnel I used to fall through. This one involves some ideas I was using in a novel I was writing two years ago, Juicy Ghosts. .

The painting is called The Halo Card. It includes the dream of being weightless in a tunnel, with up and down the same. And my characters, who have toroidal haloes, and their mascots who are little people with Happy Face heads—they’re all from my novel. And, as a third factor, there’s the symmetry you see on a playing card. The symmetry helps the 2D pattern. The symmetry is the math in this one.

I often mix my painting in with my writing. It’s a way of using different parts of my brain. I paint what I’m writing about, and I might get new ideas about what to write. My dream of the novel becomes more vivid.

In comparing painting and writing, there’s one difference that pops out. A novel or a story has a plot, a one-dimensional line. Although it does take time to make a painting, the finial result is a two-dimensional see-it-all-at-once pattern. You might say that a novel is a design in time, and a painting is a design in space?

But maybe that’s not entirely true. Here’s a nice painting called Rush Hour. Inspired by a big traffic circle in Genoa. Space or time? Those categories don’t seem quite right. It’s an integrated spacetime process. Like a puppet show in my head, a dream of what I saw.

And a novel has a spacetime quality too. People speak of a novel as a tapestry of characters and events. After you’ve read a novel, and you think about it, you do in fact see it as a world with things in it, or as a design that you can scan as a whole. So it’s more than one-dimensional after all.

Conversely, there is a bit of a time-bound, one-dimensional quality to experience a painting. You might talk about reading a painting, in the sense that you study it to see how things fit together. And it may be that as you study a painting it blooms or unfolds and you see more levels.

Here’s a painting of mine with a nice one-dimensional flow to it, moving from the edges to the center. All the critters are flying along spiral paths. Falling into the white light at the center. This painting is interesting to me because it suggests infinity, that is, an M. C. Escher infinity where we squeeze in endlessly many objects by having them shrink as they move toward the center. I gave it a bombastic name: Topology of the Afterworld.

Mathematics has always felt natural to me. Even though I wanted to end up as a writer and a painter, I studied math in college, and I went on to get my Ph. D. in set theory, a branch of mathematics that’s specifically about levels of infinity. A very 1970s thing to study. You might say that set theory is mathematical theology.

And when fractals and the Mandelbrot set came along, we mathematicians really had an idol to worship! The computer is a wonderful tool, and in the 1986s, my family and I moved to Silicon Valley and I switched from math to teaching computer science. It was a very exciting time.

I got especially interested in a type of computation called a cellular automata, or CAs. It started with a journalism gig I had, interviewing people working with CAs. I remember sitting in front of a seething screen with a CA guy, and he looked at me with wonder in his eyes. He said, “I feel like Leeuwenhoek when first he looked through the microscope.”

In a CA you think of each pixel on the screen as a tiny computer in a cell, with all the cells computing in parallel to generate gnarly, natural-seeming patterns. In Conway’s classic Game of Life, there’s simply a zero/one bit in each cell. I got interested in continuous-valued CAs that have a real number in each cell.

I did a lot of work with these analog CAs, and many of them generate a certain kind of swirl. These are called Belousov-Zhabotinsky patterns. My painting of such a process is called Soft Zhabo.

Painting this was a lot more than “dreaming while I’m awake.” With my students I designed a software package to run continuous-valued cellular automata. {You can get it from GitHub; it’s called CAPOW.) And I spent hundreds and hundreds of hours devising new CA rules and looking at the patterns they made.

When I found the particular pattern in the painting above, I printed it out, and painted a version of it. Not that the painting is totally accurate, and that’s good. It’s fuzzy, and tinged by dreams. That thing in the middle; is it a baby seahorse?

Here’s a painting called “The Riviera,” on the theme of the dance of the of the analog and the digital. One of those fundamental yin/yang divides, like male and female. You might say it’s a picture of me and my wife.

I prefer continuous, analog, processes to digital ones, but under the surface, my continuous-valued CAs are in fact being formed by a digital computer. But once I paint them, they’re fully analog again, thanks to the smear of the palette, with its blends of physical paint.

Getting back to formal mathematics, in grad school I was interested in a certain mathematical question called the Continuum Problem. Suppose that alef-null is the size of the set of all natural numbers, like {1, 2, 3, 4, …}. Digital infinity. And c is the size of the continuum, that is, the number of points in space. Analog infinity. The mathematician Georg Cantor proved that c is larger than alef-null.

Cantor’s Continuum Problem asks whether c is the very first transfinite number after alef-null.

It’s a very hard problem! As a matter of fact, and this is an odd thing about higher logic, we can prove that the Continuum Problem is unsolvable. Math as we know it is unable to decide whether there’s a transfinite number between c and alef-null.

So, to hell with proving anything! In 1979 I wrote a science fiction novel about Georg Cantor, his levels of infinity, and a young hippie math professor very much like myself. I called the novel White Light, with the not-quite-serious subtitle: What is Cantor’s Continuum Problem?

The action of the book is that my hero leaves his body and goes to a place like heaven. And in heaven there’s a mountain that’s very tall. Taller than alef-null, taller than alef-one, running all the way out to the supreme metaphysical type of infinity that Cantor called the Absolute Infinite.

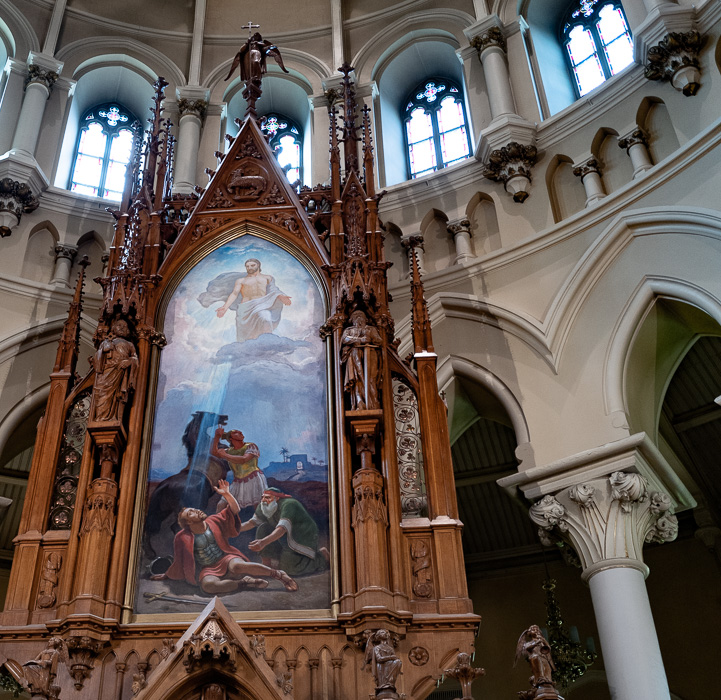

Many European churches have stained glass images of God, depicted as an eye inside a triangle. In the US, sad to say, we have our eye-in-a-triangle images on our dollar bills.

Why did I choose White Light for the title of my science-fiction novel about infinity? People sometimes use that phrase to describe a certain type of mystical vision. In grad school, I myself had a vision like this, a sense of a divine One Mind that glows in every particle of being. And I can still see it. The One is like sunlight shining through a huge stained-glass window, or like a cosmic giant whose atoms we are. The White Light is everywhere.

Logic

I already said that writing and painting are like dreaming while you’re awake But, being a mathematician, I’d like to say they’re like doing mathematics. And that’s a little bit true, but not very much.

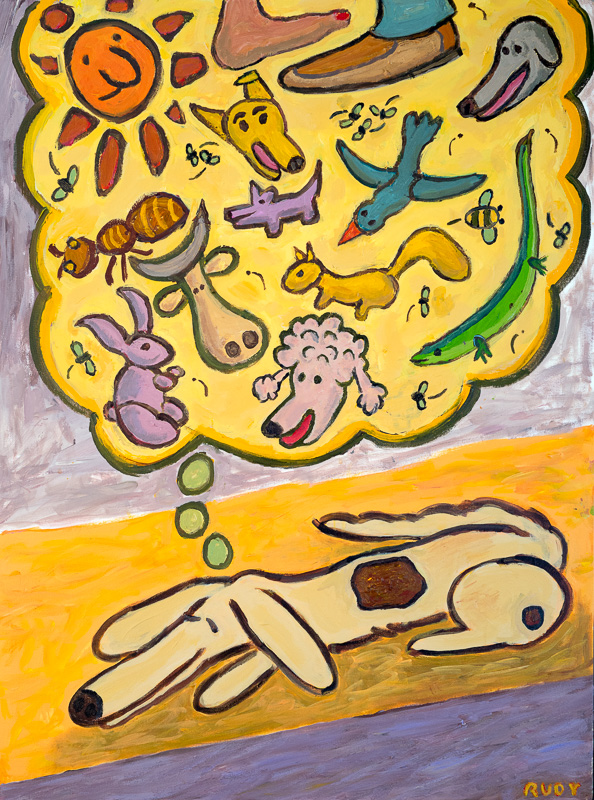

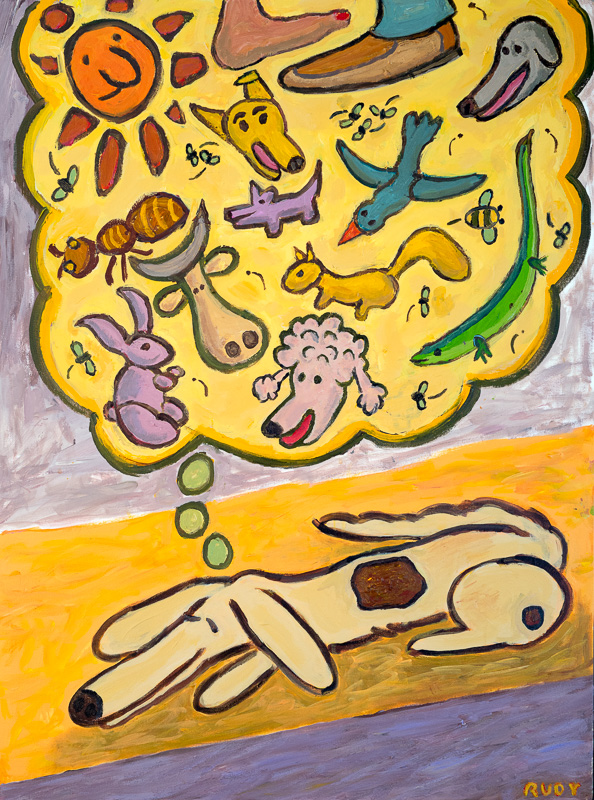

To write a novel, or paint a painting, you start with imagining a certain world. And you have some characters in mind for your world, or some scenes or objects, although these things aren’t very precisely defined. They’re more like islands glimpsed through the fog. Or maybe like the things in my painting of Arf’s Dream, shown above.

So, once I have my groundwork in place, do I know where the novel will go, or how the painting will end up? No, of course not.

The only way to find out what’s going to happen is to write or paint your way from here to there. And be inspired by all the things you see along the way. To get to a mountain top, you have to walk the trail. You can’t just hop to the peak.

It turns out there’s a result in mathematical logic that more or less proves this. It’s called Turing’s theorem. It says there’s no way to look ahead and predict what a math theory is going to prove. Given some arbitrary statement, there’s no shortcut for deciding whether the statement is probable, disprovable, or undecidable.

I love Alan Turing very much. In face I wrote a novel where he escapes death, moves to Tangier and has a love affair with the Beat writer William Burroughs. My novel is Turing & Burroughs. Burroughs has always been one of my favorite novelists. In some ways his books are like science fiction.

In my novel, Turing and Burroughs develop a method for turning themselves into shape-shifting slugs called skugs. And eventually they end up in Los Alamos, New Mexica, and have some dealings with the famous mathematician Stanislaw Ulam. Ulam invented the hydrogen bomb—and cellular automata. I had a lot of fun writing about him.

Getting back to the point I was making, if Turing tells us you can’t predict where a math theory will go, you certainly can’t predict where an idea for a novel or a painting will lead. I don’t know what those flying saucers want to do with those two people on the beach in my painting Visitors. Are the people hailing a ride? I’ll never know. And that’s okay. It’s fun to not know.

You write scenes or make marks and ask yourself what they remind you of. And if you don’t like where it’s going, you rub out what you’ve got and try that part again. The process is iterative and interactive. You have to do the work—even though you’re groping in the dark.

But what about making an advance outline or sketch? Well, sure, you can have a stab at this, just to get going. It does help to have some kind of plan when you’re well and truly lost at sea. . But don’t take your sketches or outlines for gospel—they’re just things that you randomly made up. And have no qualms about changing your plan as the work proceeds.

And, okay, some people do make novels or paintings that are predictable? But, face it, those things are no good. Didactic rehashes of tired fables. Propaganda about how the world “should” be. Not worth looking at.

So, wait, is logic worthless? No, no, no, logic is hugely helpful, so long as you don’t expect too much from it. A key teaching is to keep your novels and paintings consistent. Unless, of course, you want them to be inconsistent. But that usually doesn’t go over well.

In my own work I need to repeatedly revise the opening chapters as the later chapters emerge. Why? Because I want to maintain logical consistency. I want the early stuff to match what’s happening later on.

A beginning author or artist might think it’s too much work to insert foreshadowing scenes to prepare for late actions—or to draw in missing body parts, or straighten out a building’s lines. But really it’s not much work at all. Typically, it’s only a matter of inserting a few sentences or dabs of color. It always surprises me how easy this is. It’s only words and paint.

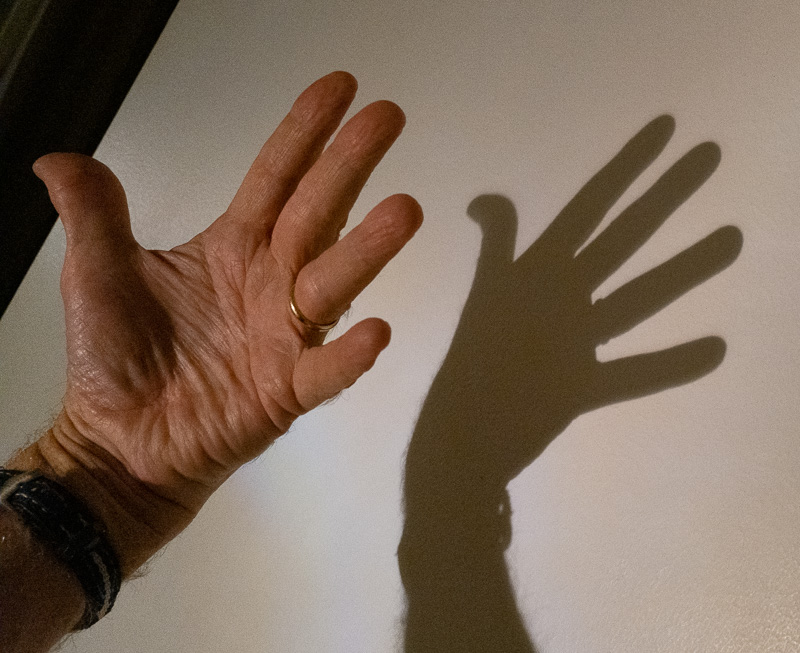

Thinking some more about prefiguring, I remember playing with our children and their cousins on the beach in Maine. I’d use a long stick to draw mazes in the beach sand for the kids to run around in. And as I drew the mazes, I’d regularly have to go back and rub out a piece of the maze wall to make a door—or draw an extra bit of line to close a door that I had. Writing a novel is like this, and so is a painting.

If I’m writing or painting from the heart, I lose myself in a maze. I beg the foggy shapes to tell me what they want to do. I petition the Muse for crazy interruptions and wild detours.

Another interesting thing, which I don’t pretend do understand. When the work goes well it helps to pay close attention to what’s happening in the world around me. When you’re really into it, you start seeing and hearing things that can go straight into your book. You’re like a magpie gathering things for her nest. The world begins dancing with you. Everything fits. Thanks to the Muse.

Gnarl

Chaos theory echoes some of the things we learn from logic. But chaos is a property of the physical world rather than being a property of pure mathematics. It’s often said that a chaotic process has the property that a very small change in the system can lead to a large effect later on. A less well-known know aspect of chaos is that objects in a chaotic system move about in wide-ranging ways.

Perhaps because I’m a Californian, I prefer using the word gnarly instead of chaotic. Gnarly like the grain of a redwood root, or like wild surf at a break, or like the intricate blends of fog and open space within a cloud.

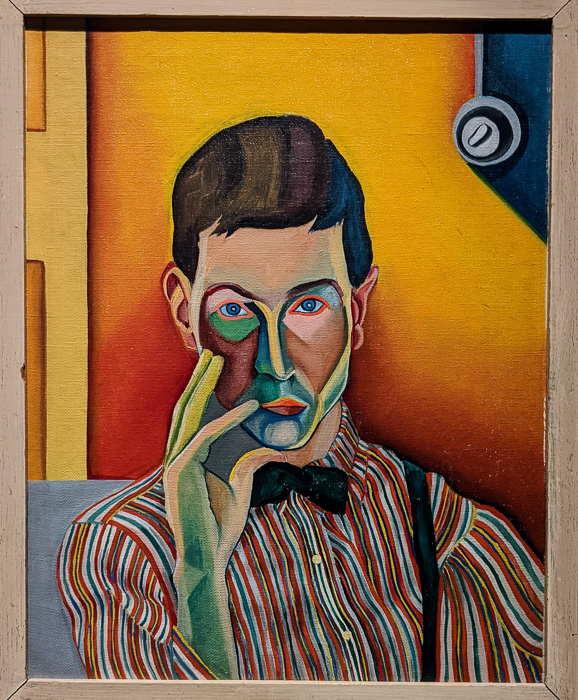

It’s easier to just show you gnarl than to talk about it. Here’s a nice gnarly painting called Self-Portrait With Mandelbrot Set UFO. This painting incorporates a wide range of my concerns. It has a cubic Mandelbrot set that I generated, a man who looks like me, gnarly tendrils, and a UFO that kidnaps cows and people.

Another way to explicate gnarl is to point out what it’s not. Looking at the spectrum of possible complexity, gnarliness isn’t at the high end or the low end—it’s in the middle.

Too Cold. Predictable. Processes that are without surprise. This may be because they die out and become constant, or because they’re repetitive. Think of a checkerboard, or a clock, or a dead person.

Too Hot. Random. Processes that are completely messy and unstructured. Think of the molecules eternally bouncing off each other in air, or a city dump, or a shuffled deck of cards.

Just Right. Gnarly. Processes that are structured in interesting ways, and that are in practice unpredictable. Here we think of a fluttering leaf, an ocean wave, a flame, a wispy cloud, a living organism, or a mind.

The gnarly natural processes are the only ones that matter. Nothing that’s predictable is of any real significance. And randomness is dull. Gnarl is where it’s at.

Gnarly processes are subject to something like Turing’s theorem. If a process is gnarly, there’s no shortcut for finding out what it’s going to do. The only way to learn precisely what the weather is going to be tomorrow is to wait twenty-four hours and see. The only way to know the final paragraph of a book is to finish writing the book. The only way to know what your new painting will look like is to complete it.

Another picture of gnarl. It’s called Jellyfish Lake. It’s a scene I saw while snorkeling in the actual Jellyfish Lake near Palau in the South Pacific. Overwhelming. All I could to was look—and revel in what I saw. The scene found its way into my novel Mathematicians in Love.

Gnarly systems have certain patterns or behaviors that they tend to form. These are called strange attractors. The strange attractors form a skeleton of order within the chaos.

When you go to the beach you don’t see a lumpy cloud of air and water above the beach. You see waves. The formation of waves is a chaotic attractor for the system of ocean and shore.

More particularly there will be certain characteristic patterns you see in a certain locale. These are more specialized chaotic attractors. If, for instance, you’re looking at the surf near a spit at the beach, you’ll notice that certain patterns recur over and over—perhaps you keep seeing a double-crowned wave on the right, a bubbling pool of surge beside the rock, and a high-flown spray of spume off the front of the rock. This particular range of patterns is a specific strange attractor.

Looking up at the sky, we note that each day’s strange attractor of cloud patterns relates to that days heat, humidity, and wind. And the strange attractor of a bonfire is highly dependent on what is burning, and on how long the fire’s been alight.

As I’ve said, gnarly chaos is a way to think about your own process of writing or painting. The processes are unpredictable. But, being a chaotic systems, you have certain patterns that you like to form. These patterns are your strange attractors. Your attractors have to do with your experience and your personality and your habits. Your develop a style. People can recognize your work.

From time to time a gnarly chaotic system undergoes a sea change, a discontinuity, a revolution. When your writing or artworks change and you enter a new period, you’ve switched to a different strange attractor—a different style or mode. Perhaps a flying jellyfish comes to your treehouse to announce the change. The painting is The Sage and the Messenger. It was a model for a story I wrote with Bruce Sterling.

And in the world at large it often happens that some event pushes the society’s chaos toward a new and different strange attractor. We hop from one strange attractor to another. The new strange attractor is different, but yet it’s generated by the same human needs: to eat, to find shelter, and to form families. From such humble rudiments doth history’s tapestry emerge endlessly various, eternally the same.

This painting is Pinchy’s Big Date. A silly painting. But fun to look at. Maybe Pinchy and the California Girl are two different strange attractors. Which one’s lap will you sit in?

Cyberpunk and Transrealism

Cyberpunk and transrealism are styles of science fiction writing. Being G. W. F. Hegel’s great-great-great-grandson, I have a genetic predisposition for dialectic thinking. We can parse cyberpunk as a synthesis. Cyber + Punk = Cyberpunk.

Cyberpunk expresses a goal regarding the coming symbiosis between humans and machines. People’s minds will be upgraded, rather than being degraded to zombie level. People will remain interested in sex, drugs, and rock’n’roll. Robots will rise to our level, rather us sinking down to their level.

One might say that you people gathered here are cyberpunks. You’re fusing math and art!

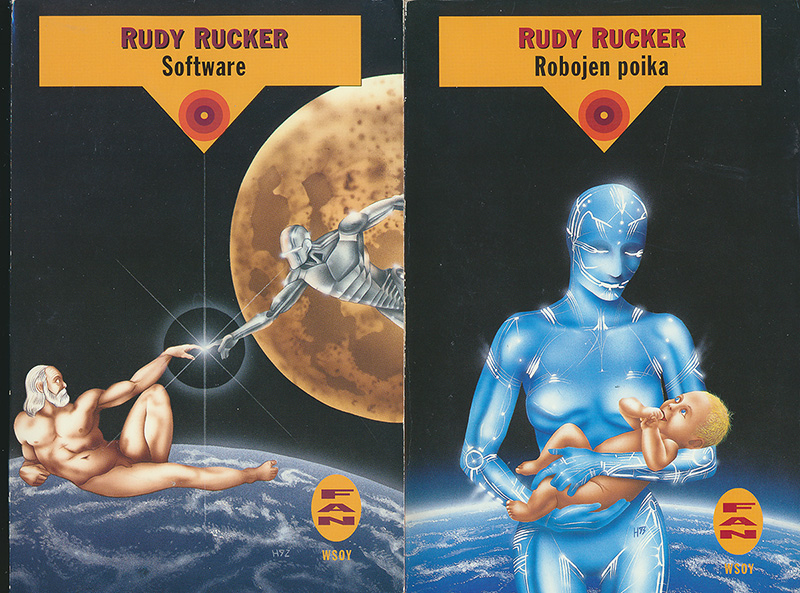

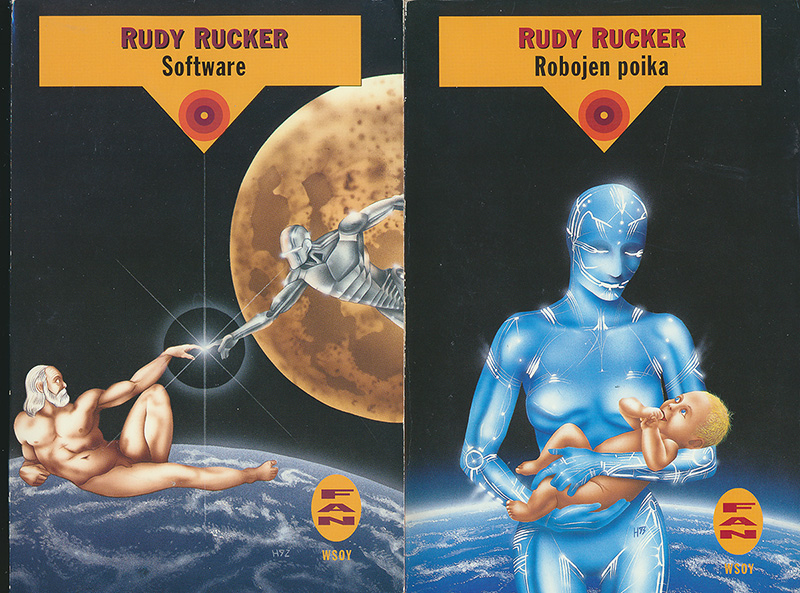

Here’s Finnish covers of my early 1980s cyberpunk novels Software and Wetware. Where it all began.

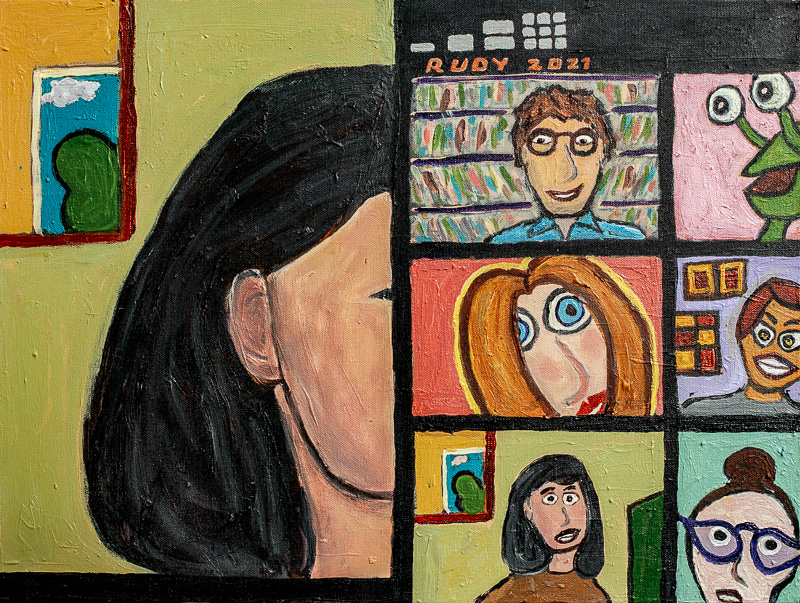

There’s another modern SF movement I’m associated with: transrealism. In a transrealist novel, you write about your immediate experience, but intensify the writing by throwing in SF notions.

Nostalgia is time travel, the oddness of strangers means they’re aliens, spiritual freedom is the ability to fly, intimate conversation is telepathy, political advertising is parasitic mind control, space travel is moving to a new city—and so on.

One doesn’t glorify the main character by making him or her be powerful, wise, or balanced. Actual people are gnarly and unpredictable, this is why it is so important to use them as characters instead of the impossibly good and bad paperdolls of mass culture.

And your paintings can show the world around you, but somehow elevated to a mythic status. I call this one The Parable of the Chickens. I don’t know what the parable is, but it looks deep.

If you turn off your news feed you can re-enter the human world. You eat something and go for a walk, with your endless stream of thoughts and perceptions mingling with nature’s gnarly inputs.

Cyberpunk and transrealism are paths to a revolutionary SF.

Art and literature are more than entertainment. They can be tools for changing the world.