I’ve been reading an advance copy Neal Stephenson’s new novel, Anathem, preparing to introduce his reading at Moe’s on Wednesday, Sept 10, 2008. The book goes on sale nationwide on Tuesday, September 9, 2008.

Anathem is heavy in every good sense of the word, one of the best SF novels I’ve read in the last couple of years. I’d put it up right there with Charles Stross’s Accelerando and my own Postsingular, not to mention the esteemed recent works of my cyberpunk pals Gibson, Sterling, and Shirley. It’s truly twenty-first century SF, amazingly broad, deep, and well-informed with, at times, the flavor of a classic philosophical treatise.

One particular SFictional/philosophical theme that Stephenson takes on in Anathem is the question of whether our consciousness might span multiple universes, as well as wider questions about ways in which alternate universes might influence each other.

Stephenson advocates a radical notion under which some possible physical universes might in fact be something like a Platonic world of forms relative to some other universes—he calls this Complex Protism, although we Earthlings might call it Complex Platonism.

The MIT physicist Max Tegmark actually has written some papers discussing a somewhat similar notion—see, for instance his online paper (PDF format) “The Mathematical Universe.”

Here’s Neal’s official website (updated as of yesterday), and a casual personal website that he sporadically maintains.

Neal likes to write long books, and I’d estimate Anathem to be some 370,000 words long, that is, three or four times the length of a typical novel such as we lesser mortals might pen. He liberally uses many made-up words, so at first you’re continually flipping back to the Glossary at the book’s end. A bit of a learning-curve, but after a few hundred pages I was totally into the book.

Rather than going into full plot-spoiling detail about the book, I’ll just paste in some passages that for one reason or another particularly pleased me, marking the quotes by indenting them with a line in the margin. Think of this as a preview reel. Most of the photos were taken in Santa Cruz, CA, this weekend.

The main characters in Anathem are a bit like cloistered academics, and often get into dialogs not unlike what you’d find in Plato’s writings. At one point, our hero and a friend are watching two colonies of ants fighting each other.

”…You look down on it from above, and say, ”˜Oh, that looked like flanking.’ But if there’s no commander to see the field and direct their movements, can they really perform coordinated maneuvers?”

“That’s a little like Saunt Taunga’s Question,” I pointed out. “Can a sufficiently large field of cellular automata think?”

Describing a revered philosopher/mathematician, Saunt Bly, who’d been expelled from his enclave:

…to live out the remainder of his days on top of a butte surrounded by slines who worshipped him as a god. He even inspired them to stop consuming blithe, whereupon they became surly, killed him, and ate his liver out of a misconception that this was where he did his thinking.

Note that “slines” are common people, and their name is derived from the central letters of “baseline.” “Blithe” is a tweaked plant that’s rich in the psychoactive agent called allswell.

Discussing how the outer word of “Saeculars” views the enclosed world of the philosophical orders:

“The Saeculars know that we exist. They don’t know quite what to make of us. The truth is too complicated for them to keep in their heads. Instead of the truth, they have simplified representations—caricatures—of us. Those come and go… But if you stand back and look at them, you see certain patterns that recur again and again, like, like—attractors in a chaotic system.”

Our hero’s mentor teaches him about the importance of seeking the gnarl in your everyday surroundings:

“That is the kind of beauty I was trying to get you to see,” Orolo told me. “Nothing is more important than that you see and love the beauty that is right in front of you, or else you will have no defense against the ugliness that will hem you in and come at you in so many ways.”

Our hero is talking to his sister about how they’re going to face a possible alien invasion. He’s recently been in a stationery store. His sister is asking what other supplies they might use to try and defend Earth. They joke like mathematicians…

“Do you need transportation? Tools? Stuff?”

“Our opponent is an alien starship packed with atomic bombs,” I said. “We have a protractor.”

“Okay, I’ll go home and see if I can scrounge up a ruler and a piece of string.”

“That’d be great.”

Discussing what it is that our ruling class really wants to take from the common people.

The Powers That Be would not suffer others to be in stories of their own unless they were fake stories that had been made up to motivate them. People … had to look somewhere outside of work for a feeling that they were a part of a story, which I guessed was why Saeculars were so concerned with sports, and with religion. How else could you see yourself as part of an adventure? Something with a beginning, middle, and end in which you played a significant part?

One of the book’s numerous definitions.

Dialog: A discourse, usually in formal style, between Theors. … In the classic format, a Dialog involves two principals … Another common format is the Triangular, featuring a savant, and ordinary person who seeks knowledge, and an imbecile.

A discussion between our hero and his mentor Orolo about what we’d call the Multiple Universes hypothesis.

“You’re saying that my consciousness extends across multiple cosmi,” I said. “That’s a pretty wild statement.”

“I’m saying all things do,” Orolo said. “That comes with the polycosmic interpretation. The only thing exceptional about the brain is that it has found a way to use this.”

By the way, my friend Nick Herbert has written a really good essay on the slippery topic multiversal consciousness: “Quantum Tantra.”

David Deutsch has also written some good stuff on multiversal computation, see my It from Qubit post on this.

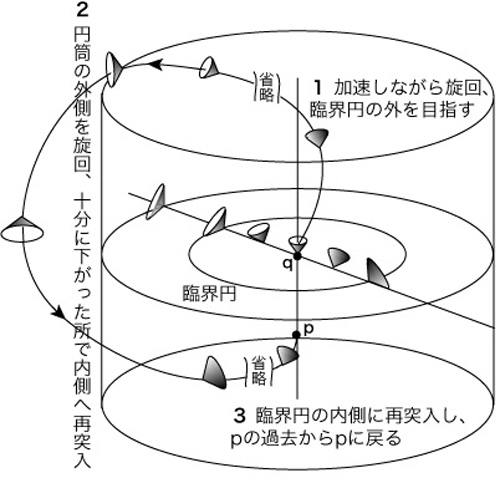

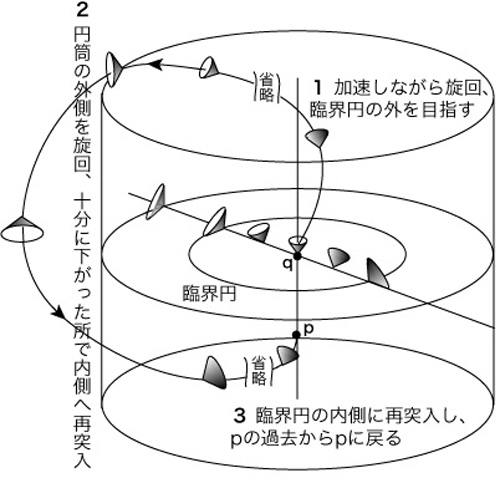

A mention of my favorite mathematician, the philosopher-king Kurt Gödel, in a discussion about Gödel’s rotating universe model, in which a sufficiently long round trip can lead back into your past!

“On Laterre, the result was discovered by a kind of Saunt named Gödel: a friend of the Saunt who had earlier discovered geometrodynamics. The two of them were, you might say, fraas in the same math.”

“Saunt,” similar to our word Saint, is a shortening of “savant.” A “math” is an enclave where dedicated scholars live, and a male scholar of this type is a fraa.

Re. Gödel’s model of the universe, see a nice essay by John Bell summarizing how it can lead to multiple universes. The cool image here is from a Japanese essay about Gödel’s universe.

The people in Anathem have something like our Internet, which is called the Reticulum.

“The functionality of Artificial Inanity still exists … for every legitimate document floating around on the Reticulum, there are hundreds or thousands of bogus versions—bogons as we call them.”

Two miles away—directly across the facet—was a hydrogen bomb the size of a six-story office building. It was essentially egg-shaped. But like a beetle caught in spider’s webbing, its form was blurred by a fantastic tangle of strut-work and plumbing…

Yaaar! We’re talking real SF!

I just finished the book, and I’m sorry to be done. Looking up into the sky, I notice a shiny…metal flying machine. My God! I live on a planet with flying machines! Oh, wait, I knew that already. Anathem makes everything seems surprising.