The physical world is not a cheapo simulation on some cruddy computer.

This is largely a repost of an earlier entry on my blog, called “Fundamental Limits to Virtual Reality.” That older post got a lot of hits and comments, and you can read my answers to some of the comments in a follow-up to the earlier post.

This new version has some fresh illos and links, and it appears on Medium as well.

Musings on whether a virtual reality or a computer generated reality could ever match our real reality.

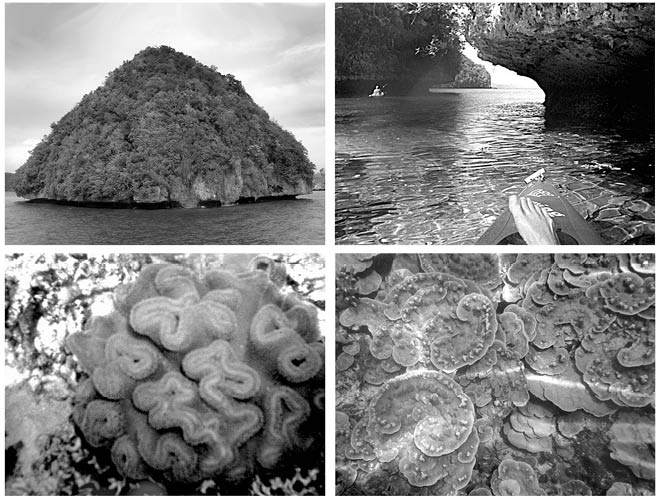

I wrote my first version of this essay in 2008, while in Pinedale, Wyoming, visiting my daughter Isabel and doing some cross-country skiing among the aspen trees. The trees have great patterns like eyes on them. Nice examples of a RR “real reality” richer than any VR “virtual reality” we’re ever going to see.

In my novel Postsingular I argued that it’s bogus to talk about porting humanity into a complete virtual model of Earth. Call it “Vearth.” You’d lose a lot. So today I want to explain some of the reasoning behind my claim.

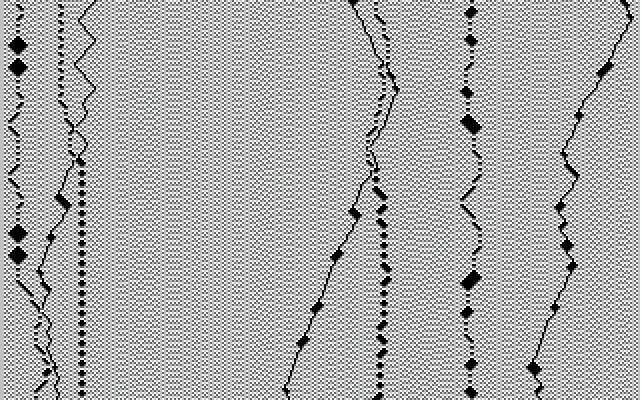

Arguments for Vearth are sometimes start by talking about an imaginary substance dubbed “computronium. The word was, I believe coined by two brilliant, eccentric, wild computer scientists Norman Margolis and Tommaso Toffoli who designed the so-called CAM boards for running rapid cellualar automata computations in the early 1990s.

I myself as drawn into the Margolis-Toffoli orbit, and I did a lot of work with cellular automata, as described in my autobio. See also the digital Cellab I worked on with John Walker, and the gnarlier analog CAPOW ware I developed with my students at San Jose State.

One of my favorite SF writers, Charles Stross, wrote a fab postsingular novel In Accelerando, where he says computronium is “matter optimized at the atomic level to support computing.”

It’s a fun idea to get really literal about it. But I think computronium is a fundamentally spurious concept, an unnecessary detour. Matter, just as it is, carries out outlandishly complex chaotic quantum computations just by sitting around. Matter isn’t dumb. Every particle everywhere everywhen is computing at the maximum possible rate. I think we tend to very seriously undervalue quotidian reality.

In an extreme vision”Š—”Šwhich is the one I dispatch in chapter one of Postsingular”Š—”ŠEarth is turned into a cloud of computronium which is supposedly going to compute that Vearth or virtual Earth which is even better than the one we started with.

This would be like filling in wetlands to make a multiplex theater showing nature movies, clear-cutting a rainforest to make a destination eco-resort, or killing an elephant to whittle its teeth into religious icons of an elephant god.

Ultrageek advocates of the Vearth scenario like to claim that nothing need be lost when Earth is pulped into computer chips. Supposedly the resulting computronium can run a VR (virtual reality) simulation that’s a perfect match for the old Earth.

As I’ll explain below, this is factually incorrect and, even in priciple, impossible. Before getting into that, I might also ask why someone would passionately want to believe that we can be translated from flesh into bits? There’s something ascetic and life-hating about the notion. It’s a bit like a religious belief; one thinks of the old “work now, get rewarded in heaven” routine.

Anyway, let’s get back to my main point, which is that VR isn’t ever going to replace RR (real reality). We know that our present-day videogames and digital movies don’t fully match the richness of the real world. What’s not so well known is that computer science provides strong evicence that no feasible VR can ever match nature.

This is because there are no shortcuts for nature’s computations. Due to a property of the natural world that I call the “principle of natural unpredictability,” fully simulating a bunch of particles for a certain period of time requires a system using about the same number of particles for about the same length of time. Naturally occurring systems don’t allow for drastic shortcuts.

For details see The Lifebox, the Seashell and the Soul, or Stephen Wolfram’s revolutionary tome, A New Kind of Science”Š—”Šnote that Wolfram prefers to use the phrase “computational irreducibility” instead of “natural unpredictability”.

Natural unpredictability means that if you build a computer sim world that’s smaller than the physical world, the sim cuts corners and makes compromises, such as using bitmapped wood-grain and cartoon-style repeating backgrounds. Smallish sim worlds are doomed to be dippy Las Vegas/Disneyland/Second Life environments.

In Memory of Michael Blumlein (1948 – 2019)

But wait, answer the true-believer ultrageeks, if you do smash the whole planet into computronium, you have potentially as much memory and processing power as the intact planet possessed. It’s the same amount of mass, after all. So then we could make a fully realistic world-simulating Vearth with no compromises, right?

Wrong. Perhaps you can get the hardware in place, but there’s the vexing issue of software. Something important goes missing when you smash Earth into dust: you lose the information and the embodied software that was embedded in the world’s behaviors. An Earth-amount of matter with no high-level programs running on it is like a powerful new computer with no programs on the hard drive.

Ah, says the VR true believer, what if the nanomachines first copy all the patterns and behaviors embedded in Earth’s biosphere and geology? What if they copy the forms and processes in every blade of grass, in every bacterium, in every pebble, and so on?

But, come on, if you want to smoothly transform a blade of grass into some nanomachines simulating a blade of grass, then why bother pulverizing the blade of grass at all? After all, any object at all can be viewed as a quantum computation! The blade of grass already is an assemblage of nanomachines emulating a blade of grass. To the extent that you can realize an accurate VR world, the exercise becomes pointless.

Just as she is, Nature embodies superhuman intelligence. She’s not some piece of crap to tear apart and use up.

But wait”Š—”Šif you do smash the whole planet into computronium, then you have potentially as much memory and processing power as the intact planet possessed. It’s the same amount of mass, after all. So then we could make a fully realistic world-simulating Vearth with no compromises, right?

Wrong. Maybe you can get the hardware in place, but there’s the vexing issue of software. Something important goes missing when you smash Earth into dust: you lose the information and the software that was embedded in the world’s behavior. An Earth-amount of matter with no high-level programs running on it is like a potentially human-equivalent robot with no AI software, or, more simply, like a powerful new computer with no programs on the hard drive.

Ah, but what if the nanomachines first copy all the patterns and behaviors embedded in Earth’s biosphere and geology? What if they copy the forms and processes in every blade of grass, in every bacterium, in every pebble”Š—”Šlike Citizen Kane bringing home a European castle that’s been dismantled into portable blocks, or like a foreign tourist taking digital photos of the components of a disassembled California cheeseburger?

And, like I already said, if you want to smoothly transmogrify a blade of grass into some nanomachines simulating a blade of grass, then why bother grinding up the blade of grass at all? After all, any object at all can be viewed as a quantum computation! The blade of grass already is an assemblage of nanomachines emulating a blade of grass. Nature embodies superhuman intelligence just as she is.

Why am I harping on this? It’s my way of leading up to one of the really wonderful events that I think our future holds: the withering away of digital machines and the coming of truly ubiquitous computation. I call it the Great Awakening.

I predict that eventually we’ll be able to tune in telepathically to nature’s computations. We’ll be able to commune with the souls of stones.

This “Great Awakening” will eliminate nanomachines and digital computers in favor of naturally computing objects. We can suppose that our newly intelligent world will, in fact, take it upon itself to crunch up the digital machines, frugally preserving or porting all of the digital data.

Instead of turning nature into chips, we’ll turn chips into nature.

Some of these ideas also appeared in an essay of mine “The Great Awakeining,” and you can read the essay free online. It appeared in Asimov’s SF magazine in August, 2008, and in the anthology Year Million, edited by Damien Broderick, from Atlas Books in August, 2008.

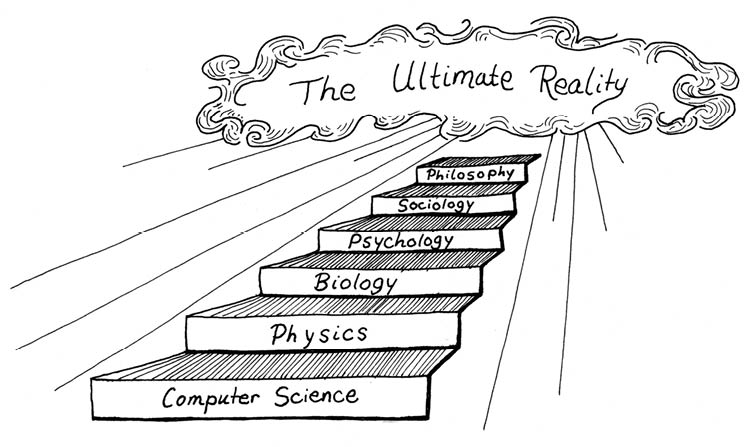

Drawing by Isabel Rucker.

Drawing by Isabel Rucker.