So I finished that painting I was talking about in my last blog post. Before getting into the details, I want to mention that I just started a big sale on my paintings, with the sale lasting till October 15, 2014. If you’re curious about that, check my online Paintings page.

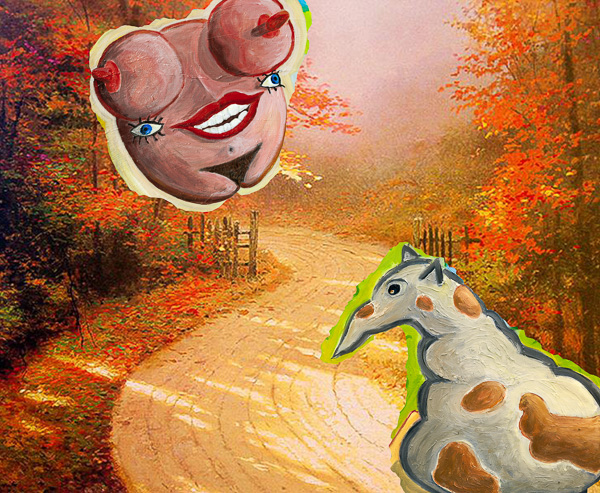

Anyway, here’s that new painting. I did quite a few revisions on it. As I’ve said before, the way to tell when your painting is done is when it stops bothering you. I like how it ended up. The paint is nice and thick, with a rich glow of colors.

“Endless Road Trip” oil on canvas, Sept, 2014, 30” x 24”. Click for a larger version of the painting.

Endless Road Trip shows my alien characters Flook and Yampa, driving their hover car across the unending plains of the unfurled “Wacker World” Earth that I’m hoping to write a novel about. (I may call the novel Endless Road Trip or, to make it easier on myself, I might make it Million Mile Road Trip. Not as far!)

Anyway, Fook and Yampa are admiring a capybara and some squirrel monkeys. My heroes Willy and Alma are along for the ride, but you don’t see them in the picture, partly because I didn’t feel like struggling with the human form—I just went for some expressionist zigzag aliens.

This place where they’ve stopped—way, way west of California—was going to be called the Land of the Ants, but then I got into a capybara-and-squirrel-monkey routine, so that’s what’s in the painting.

I like how the guy Flook on the left looks, he’s like a cartoon-character tough guy with a whiskery jaw, and the round thing on top of his head might be a derby. And Yampa on his right, she’s looking at the squirrel monkeys and the capybara and saying, in a screechy discordant voice, “Aww, aren’t they cute!” Maybe her voice is so horrible that one or more of the animals dies in some weird way. Turns into dark energy or some such.

There’s a nice new reprint of my nonfiction book The Fourth Dimension, from Dover Books. The subtitle is “Toward a Geometry of Higher Reality. There was also an edition where I used a different subtitle, “And How To Get There” — but these are the same books. The Fourth Dimension is probably my all-time best-seller, maybe a quarter million of them out there. Over the years, scores of people have written me to tell me that this book changed their lives. It’s one of my main works.

I’m happy to see it reissued by Dover, as I got my start studying Dover’s inexpensive reprints back in Louisville, Kentucky, in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

The Fourth Dimension in Kindle and paperback on Amazon..

Go git it.

Back to the new novel I’m trying to start. Wacker World. Today I’ll share some semi-technical thoughts on writing. When starting a novel I always have to decide about what point of view or POV to use. I always use either first-person (1POV) or third person (3POV).

Writing first person or 1POV is probably the easiest style. I used it in Jim and the Flims, and in The Big Aha. A no-brainer, like falling off a log. If you get the right narrator voice going, it works very well.

This said, the first-person point of view carries some risks.

(Risk 1) In that 1POV filters everything through narrator’s attitudes and language skills—and this can be an irritating feature if it’s done wrong. I don’t to see page upon page of gushing, slobbering, emoting—what I call repetitious wheenk. The first-person narrator can suck all the air out of the room.

(Risk 2) When using 1POV, there’s a sense that you need to impose the narrator’s linguistic limitations and quirks on the text. This can be okay if the author makes the viewpoint character fairly interesting, rounded, and non-generic. But it’s very risky to try and narrate a 1POV story in dialect. Unless you’re Mark Twain writing Huckleberry Finn. Although, come to think of it, I did something like this in my shot at a great American SF novel, The Hollow Earth, which is 1POV from a boy from Killeville, Virginia.

(Risk 3) Another issue with 1POV, is that the author may feel it necessary to have a frame-tale explanation of how and why and when the character is telling us about his or her adventures. You say that the narrator is reminiscing about the events afterwards, or documenting them for the record, or narrating them to a rapt audience, like that. But you don’t have to do the frame-tale, and, if done wrong, it can be of corny and obtrusive. Sometimes it’s better to just have the reader be in the narrator’s head with no explanation.

A final point to make about 1POV is that, if you want a reportage feel, you can have several characters telling the story from their points of view, or even interrupting each other, as if doing a joint interview. This could be fun. (Cat calls, loud farting sounds, sarcastic laughter.)

Regarding third person point of view or 3POV, here’s a link to a nice little essay by a writer called Michael Neff, he talks about the levels of 3POV, distinguishing 1POV, far 3POV, and close 3POV, which we can abbreviate as C3POV.

I like the C3POV, where my viewpoint is closely focused on one single character at a time. I’m following one character and seeing his or her thoughts. The C3POV is also called “third person limited point of view” or “deep” third-person. It’s like following a movie actor with a camera.

If you do C3POV instead of 1POV, you’re free to use a more literate style than the character would—I think of John Updike’s magisterial Rabbit tetralogy, of the tints and shades of feeling that are assigned to the everyman-type Rabbit Angstrom.

Note also that you’re free to adjust the “closeness” of the C3POV over the course of a scene, at times getting in so close that it’s as intimate and telepathic as 1POV.

Over the years, I’ve come to enjoy using what I might call rotating close third person point of view, or RC3POV. The idea is that I shift the close third person POV from character to character. I don’t do the shifts within a scene, I cycle from one character to another from chapter to by chapter. I did that in Realware, Postsingular, and Hylozoic. I plan to use RC3POV in my upcoming Wacker World, that is, I’ll have close third-person C3POV on my character Willy in some chapters, and have the camera on my co-starring character Alma in other chaps.

Thinking back to Postsingular, I rotated the C3POV focus from section to section within the chapters, using seven different points of view in all. And in one single section I went kaleidoscopic on the reader’s ass, hopping one head to the next without even signalling the changes with section breaks.

It’s risky to do head-hoppping, or “wandering POV,” although Thomas Pynchon and Phil Dick often do. Pynchon can do it because he’s a supreme and god-like master, and Phil, well, you never know. Phil wrote really fast and he might not even have noticed he was doing it. But getting Phil’s reckless downhill-racer thing going is a skill in itself.

Through the dancing sunlight, and into oblivion.