I’m about two-thirds done with an Escher-inspired painting that I’m calling “Topology of the Afterlife.” I probably won’t get around to finishing it until mid-August.

I mentioned my motivations for this painting in a post the other day. In a nutshell, the painting has to do with my ideas about the afterworld, Flimsy, that appears in my novel-in-progress, Jim and the Flims. I see Flimsy as being tiny, down at the lowest level of space scale. I think of it as being what Leibniz calls a monad.

Now, it wouldn’t make sense for tiny Flimsy only to be in one particular location, so I’ll assume that it’s an ubiquitous monad. That is, Flimsy is inside every particle of matter and space.

You might say that the copies are in synch, like mirror-balls. But it would be more accurate not to say that the Flimsy monads are different views of one and the same thing. The One that underlies everything.

Here’s the win with this approach: if Flimsy is to be found within every particle of the universe, then Flimsy can serve as a stargate.

Like, I shrink down into Flimsy, and then ooze out of it onto the surface of planet Bex in the Whirlpool Nebula!

Now another issue comes up. If Flimsy is going to be housing the souls of aliens from throughout our universe, then I need for the place to be very large, perhaps even infinitely big—even though it’s smaller than an electron.

I can do this by using a space-warp trick: the center of the Flimsy-ball is negatively curved space that spikes out, with an unattainable center that is literally at infinity. God’s Eye.

Putting it differently, you might say that you can’t reach the center of Flimsy because you keep shrinking as you get closer and closer to it.

I first used this idea in 1979 when I was writing my novel White Light. I wanted to describe a terrace outside the infinite Hilbert’s Hotel, a terrace which has alef-null tables (that is, as many tables as there are natural numbers.)

After an indefinite interval of time I woke up with a start. I was covered with sweat, confused. The light outdoors hadn’t changed. The phone was ringing and I picked it up.

It was the clerk’s smooth voice. “Professor Hilbert is having tea on the terrace with some of his colleagues. Perhaps you’d care to join them. Table number 6,270,891.”

I thanked him and hung up. The terrace was reached by passing through the lobby. From outside, the terrace had looked fairly standard, with about fifty tables around the circumference. But now that I was on it I could see that everything shrank as it approached the middle…so that there were actually alef-null rings of tables around the terrace’s center.

Already about ten rows in, the tables looked like dollhouse furniture, and the gesticulating diners like wind-up toys. To find Hilbert I’d have to go in better than a hundred thousand rows. Fortunately there was a clear path in, so I could run.

[A melancholy picture of now-deserted Virgin Record Store at Powell and Market St. in San Francisco. A mirror across the empty room reflects me looking in through a plate-glass window. As chance would have it, White Light was orginally published by Virgin Books, a short-lived offshoot of the record company.]

The space distortion affected me without my feeling it. When I got to the dollhouse tables, I was doll-sized and they looked perfectly normal to me. I sped towards the center, staring at the strange creatures I passed.

… Each table had a little card with a number on it, and when I got into the six millions I slowed down a little. There were so many creatures. The endless repetition of individual lives began to depress me…the insignificance of each of us was overwhelming. My vision began to blur and all the bodies on the terrace seemed to congeal into one hideous beast. I lost my footing and slipped, knocking a waiter off his foot.

… Before long I spotted three men sitting at a table, two in suits and one in shirtsleeves. With a sudden shock I realized I was looking at Georg Cantor, David Hilbert and Albert Einstein. There was an empty place at their table. I hurried over, introduced myself and asked if I could join them.

I’d already been thinking along these lines, being inspired by the classic Zeno Bisection paradox, which notes that the infinite sum of a half plus a quarter plus an eighth plus a sixteenth and so on…equals one. But I’m pretty sure that I originally got the 2D version from Escher, I already had a book of his images by then.

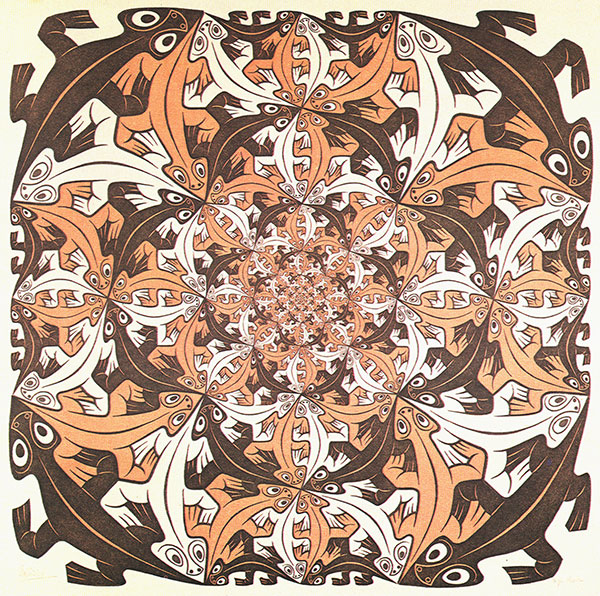

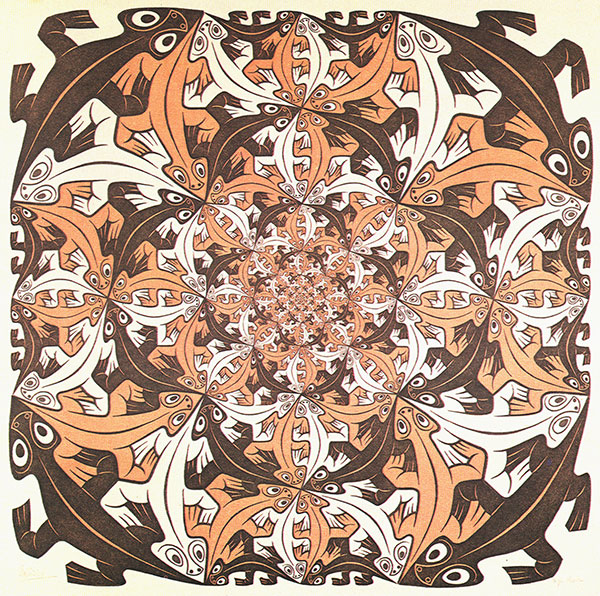

Indeed Smaller and Smaller I, a wood engraving of 1956, Escher represents this type of “infinite terrace” by a tessellated square in which the inner tiles grow smaller and smaller as they near the center.

Copyright M. C. Escher. Visit the Escher gallery and shop for more info.

Discussing this piece in the wonderful old book, The Magic Mirror of M. C. Escher, his friend and editor Bruno Ernst writes:

“Escher took things to fanatical lengths and, using a magnifying glass, cut out little figures of less than half a millimeter. For the center of the wood engraving Smaller and Smaller I he purposely used an extra block of end-grain wood so that he could work in finer detail.”

I love it when artists or authors are fanatical about their craft.

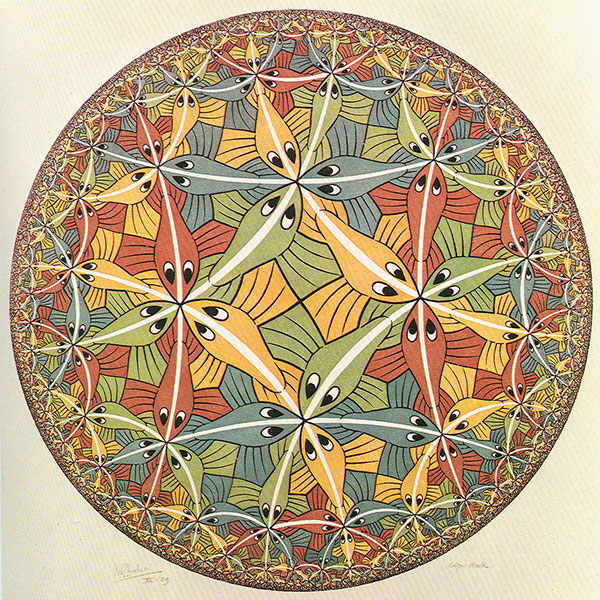

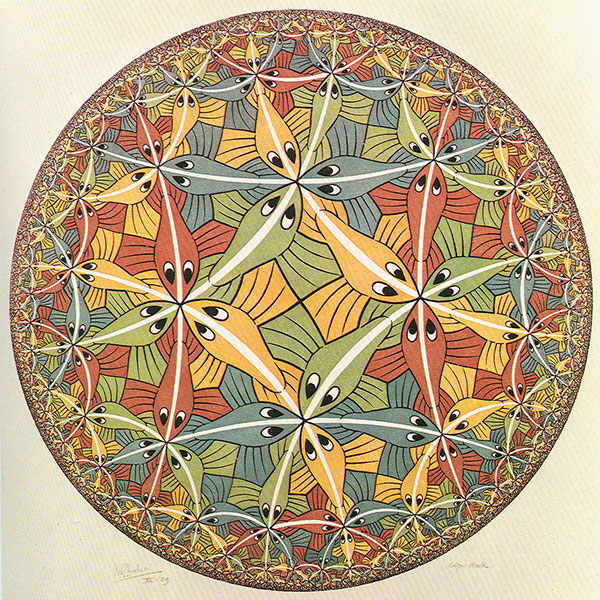

I should also mention that Escher was also interested in the “opposite” way of fitting infinity into a finite region: drawing a disk in which things shrink as they get nearer to the circumference. This appears in Circle Limit III, a woodcut from 1959.

Copyright M. C. Escher. Visit the Escher gallery and shop for more info.

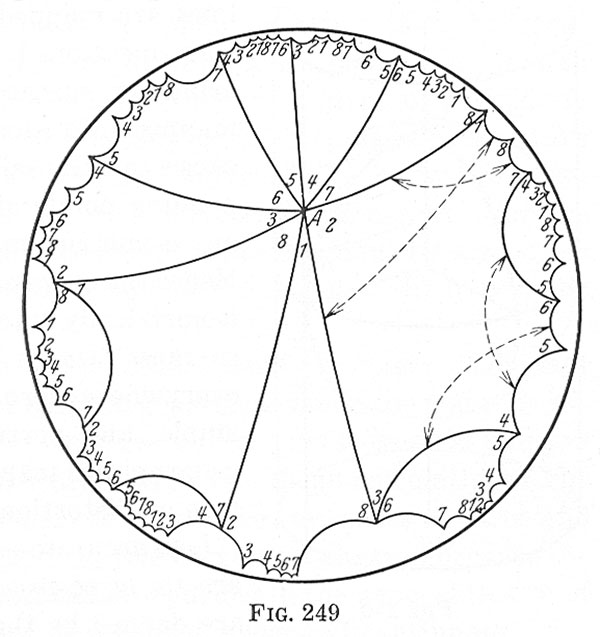

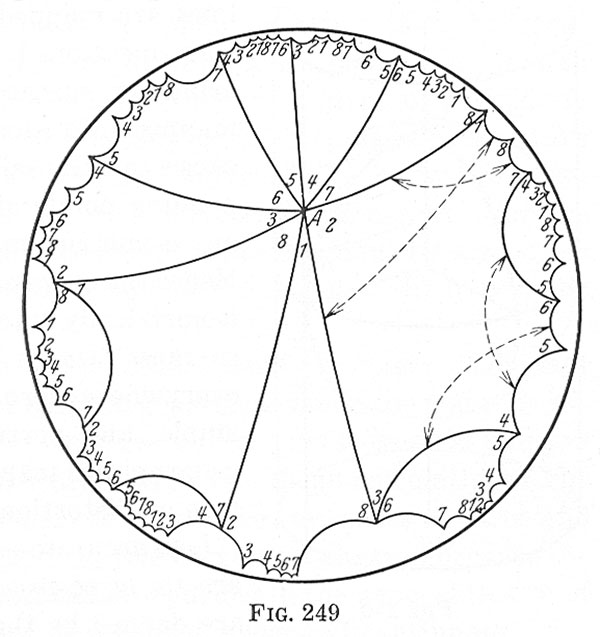

Escher’s inspiration for this pattern seems to have been a mathematical diagram of Poincaré’s model of hyperbolic geometry.

[Illustration from D. Hilbert and S. Cohn-Vossen, Geometry and the Imagination]

Although in many ways more beautiful than the shrink-towards-the-center model of the Hilbert’s Hotel terrace, this hyperbolic model isn’t suitable for Jim and the Flims—because I want my explorers to be coming into Flimsy through a bounding wall of living water. And if there’s an endless regress piled up at the edge, then it’s very hard to come in though that. If there’s in an infinite expanse towards the middle, that leaves open the possiblity of many adventures.