Today’s blog offering is an excerpt from the current draft of my novel in progress, Jim and the Flims. What I’m posting today is based on the notion that my characters Jim and Weena are off in the afterworld called Flimsy, visiting with the mathematician Charles Howard Hinton. Hinton is carrying out an exceedingly extravagant computation along the lines that I outlined in my recent post, “Breaking the Bank of Computation.”

Hinton’s not using a computer. He’s using a giant geranium plant that’s fueled by vast amounts of the aethereal substance called kessence. And the shape he’s studying? He calls it the Quest Rose.

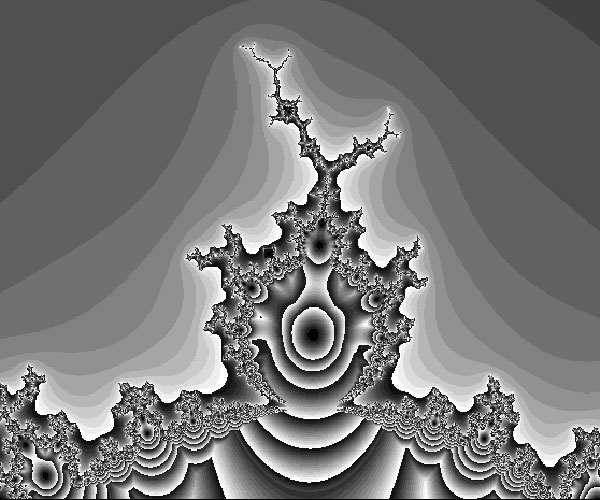

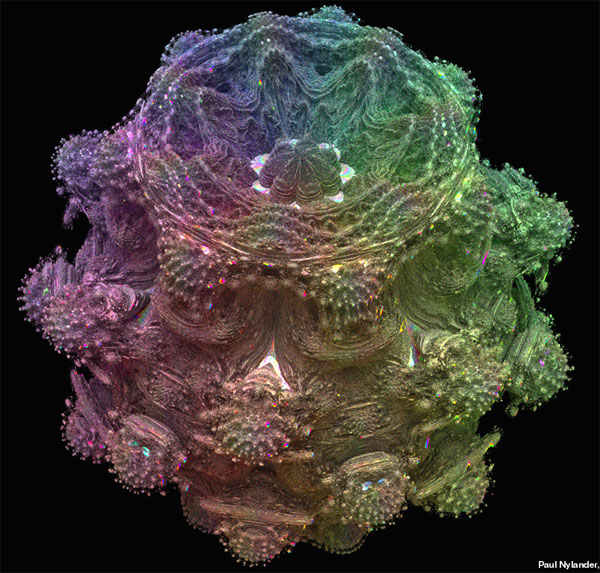

My mental model for the Quest Rose is a very cool three-dimensional fractal rendered by Daniel White, and recently posted on Fractal Forums. I show a detail below, and you can learn more about it by following some of the links in my post, “In Search of the Mandelbulb.”

Okay, so here we go with the excerpt from the draft version of Jim and the Flims. Do keep in mind that this passage is only an early draft, and I’ll be editing it a zillion more times. But I’ll leave this posted excerpt as it is, as a relic. A precursor of the finished product.

Oh, I should also mention that the Flims want to send Jim to earth with a jiva egg case designed to drain Earth’s vim in order to fuel the Quest Rose project, and that Jim is currently controlled by a parasitic jiva named Mijjy that lives inside his soul.

For most of today’s illustrations, I used my macro lens and went around the house and yard looking for interestingly gnarly things.

Not talking much, Weena and I cruised out through a door in her leaf and let the tendrils sweep us down the geranium’s stalk to the looming bulge that held the Quest Rose. A little hole near the gall’s top allowed us entrance.

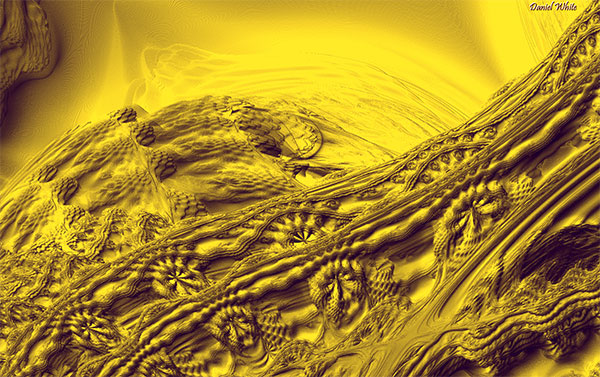

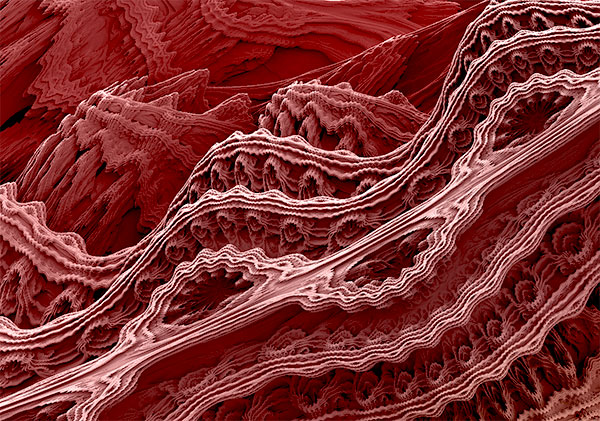

A wondrously surreal marvelous landscape lay inside. We alit upon a ridge of woven furrows, with a deep view across gorges, undulating hills and ranges of mountains. The space within the gall seemed to be warped to an enormous size—I couldn’t really see to the opposite side.

The flow of the nearby terrain was Alpine—peaks alternated with saddles, and a deep valley meandered off to our right. Low, swooping walls wove back and forth along the ridges of the landscape, dancing in syncopated rhythms. The slopes of the valley were terraced as if by rice paddies, with puckered craters within the level spots. The lace-edged craters held their own little worlds of shapes, with dim tunnels leading who knew how far below.

The Quest Rose was an outgrowth of the geranium plant itself, a bit like a wildly growing cancer. The material making up this extravagant outgrowth was kessence of a very fine type—translucent and delicately shaded, like the substance of those geck lizards I’d seen. Yellows shaded to greens and mauves.

The level of detail went down to the smallest visible levels—the ridge around me was lush with plant-like shapes. Something like a prickly pear cactus stood slumped beside me, and its pads were nappy with a grid of tiny snouts.

And all the time, every bit of the Quest Rose was moving, but so slowly that I didn’t initially notice it. But now the prickly-pear nudged me, and when I glanced back into the valley, I saw that its walls had steepened, and that a row of cavernous tunnels had opened up. Everything was morphing, every part of the Quest Rose was ceaselessly probing for new configurations.

Call it art or call it science, it was very easy to believe that this supreme work was tearing through inconceivable amounts of kessence in its eternal progress towards greater levels of beauty and gnarl. So much kessence that the Duke was bent on draining my home planet dry.

Remembering this, I began to doubt the value of the Quest Rose. Yes, it was beautiful, but so was planet Earth. Was not a forest or a reef as lovely as this warped and unnatural form? How was the Quest Rose being generated, anyway? What was Hinton’s game?

Weena turned her face up, as if sniffing the air, then led me down the slope of a nearby gulch. We made our way to a trellised balcony three tiers down, a gently curved ledge with fresh doorways opening up and others closing off, everything shimmering with subtle layers of hue. Leaning on the porch’s wavy railing was Hinton himself.

“Jim Oster?” he said, looking at me. He was a solidly built man with a pleasant face and dreamy eyes. He reached out his hand towards me. He had a yuel-made body like Durkle’s, and his arm stretched a little farther than seemed quite natural. I took his hand.

“Hello, Charles,” I said. “This—this is exquisite.”

“The Quest Rose,” said Hinton. “Maybe I’ve gone too far, I don’t know. I feel bad about the debts. But I keep hoping to find—it’s hard to explain.”

“How is it designed?” I asked, sitting down on the soft floor. Weena stood to one side, watching us.

“Oh, you know,” said Hinton. “Math. You don’t want a lecture. The basic idea is that there’s a parameter space of possible higher-order fractals, and I’ve set this mass of kessence to continually looking for the best one. At this moment, the Quest Rose is quite lovely, but what if we grow a mountain over there, or perhaps another valley? Should the crater-mouths be shaped like eights? The kessence figures out the options and, knowing my taste by now, the Quest Rose morphs smoothly towards the next pattern that I might like. You might say I’m tracing a search through a dimensional parameter space. Climbing a heavenly hill.”

“Don’t start tutoring him, Charles,” said Weena. “Jim’s just a retired postman. We’re sending him to Earth with an egg case of jivas tomorrow. They’ll drain off enough kessence to get the Solsols and the Bulbers off our necks.”

“That might be nice,” said Hinton mildly.

“But Weena just told me the jivas might destroy our planet,” I put in, unsure of how much authority Hinton might have here. “You wouldn’t want that to happen, would you, Charles?”

“Destroy the Earth?” Hinton smiled. “In a certain mood, I might say it would serve them right for running their universities like factories and for laying me off.” He shook his head. “But I’m joking. There’s the children to think of, the young lovers, the men and women in the full vigor of life. Of course we shouldn’t harm Earth.”

“And we won’t, Charles,” said Weena easily. “You shouldn’t worry about it at all. Your great work is more important than mere bookkeeping.”

“Well—maybe yes,” said Hinton, fiddling with a row of puckers in the floor beside his hand. “And I’d really like to add a few more parameters pretty soon. If we can get enough kessence into the plant.”

I wanted to tell Hinton that Weena was a liar. But Mijjy was monitoring me, making it impossible to say or to teep the proper words.

“What’s the Quest Rose actually for?” was the best I could manage.

“I’m waiting for something. I’m not sure what. The image of a lost love. A shape so arcane as to provoke notice by the great mind of Flimsy itself. An invocation of the hidden God? Tarry with me, Jim, and we can talk it over.”

“I’d like that,” I said. “I don’t really have much to do here. I’m kind of a prisoner right now.”

Hinton glanced over at Weena. Was that a glint of cunning I saw in his gentle eyes? “You don’t have to stay, Weena. I know you have things to do. Leave Jim. His jiva and I will watch over on him.”