First I’ll mention three talks in this post. And later, at the end, I add an update about the PDA 2011 con at Internet Archive.

(1) On Friday, February 25, at 4:45 pm, I spoke for a half hour on “Lifebox Immortality” at PDA 2011, a Personal Digital Archiving conference at the awesome Internet Archive in San Francisco—which is housed in a repurposed, Greek revival style Christian Scientist church, shown above

For background on my lifebox idea, see my recent post on “Digital Immortality Again.” I used “lifebox” to mean a digital or online simulacrum of a person. I go into considerable detail about the lifebox in my non-fiction book, The Lifebox, the Seashell, and the Soul, and in a recent article “Lifebox Immortality” in h+ magazine.

In a nutshell, my idea is this: to create a virtual self, all I need to do is to (1) Place a very large amount of text online in the form of articles, books, and blog posts, (2) Provide a search box for accessing this data base, and (3) Provide a nice user interface.

I made a first crude stab at this a couple of months ago, with my Rudy’s Lifebox page at www.rudyrucker.com/blog/rudys-lifebox. This page lets you Google-search my rather large www.rudyrucker.com site.

[A skyline in San Sebastian, Spain]

(2) Rick Kleffel made a nice podcast of a reading I did of “The Birth of Transrealism,” a chapter from my forthcoming memoir, Nested Scrolls: A Writer’s Life, back on January 15, 2011, in San Francisco at the SF in SF gathering. Here’s his post about the podcast on his blog, “The Agony Column.” You can also get to the podcast via , click the icon below.

(3) A videotape of my Garum Day talk in Bilbao is now online as well.

[Rudy being a Continental writer in his new *eeek* Basque beret]

You can find my description of my Bilbao talk in my recent post, “Selling Yourself”. It relates to the lifebox theme as well.

(Back to 1) Now for some notes on the PDA 2011 meeting at the Internet Archive.

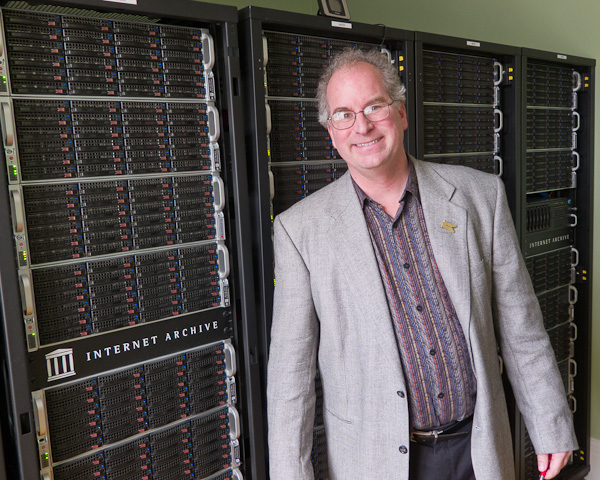

As I mentioned above, the venue was in an amazing building. Brewster Kahle (shown above with his server) acquired it a year or two ago for housing the Intenet Archive. Instead of air-conditioning the servers, Brewster has fans drawing air through them…and the air cycles into the building to heat it.

Good old Ted Nelson gave a talk, to some extent promoting his awesome autobiography, Possiplex.

Gordon Bell, the famous lifelogger was there. I stood next to him and talked to him for a few minutes—a genial guy. And the SenseCam he wears around his neck must surely have taken my picture. So I’m safe in his lifelog!

Cathal Gurrin of Dublin City University was wearing a SenseCam as well, he’s accumulated I think 7 million photos over four years, it takes about 3 shots a minute. Searching the database is the hard problem. I asked him the two obvious privacy questions, and he said he reflexively pauses it for 5 minutes as he walks into a restroom and…he takes it off at night so it can recharge.

And my old pal Faustin Bray from the Hacker and the Ants days was there as well, looking good and, as always, taping and filming for her Sound Photosynthesis site, which features Richard Feynman, Terence McKenna, Robert Anton Wilson and other freaky luminaries.

The meeting had an interesting vibe of a whole lot of people turning up and discovering that there were others interested in the same thing—logging aspects of our lives in digital forms. One thing that struck me was that everyone has their own very distinctive notion of what they’d like their lifebox to be like. In a way, it’s similar to the way that people select different kinds of statues for putting over their graves! Virtual funerary monuments. Ghostly pyramids of Cheops. I’m telling you, this is going to be a huge industry.

More: Daniel Reetz gave a great talk on the impact of ubiquitous low-cost cameras, especially as relating to DIY Book Scanning. And Rich Gibson gave an inspiring and relaxed presentation of the new movement towards gigapixel (and larger) photos, see the Gigapan site. I also met Evan Carroll, co-author of Your Digital Afterlife…this book was mentioned the recent New York Times Sunday magazine article about digital immortality.

Videos of the talks will be up in a week or two.