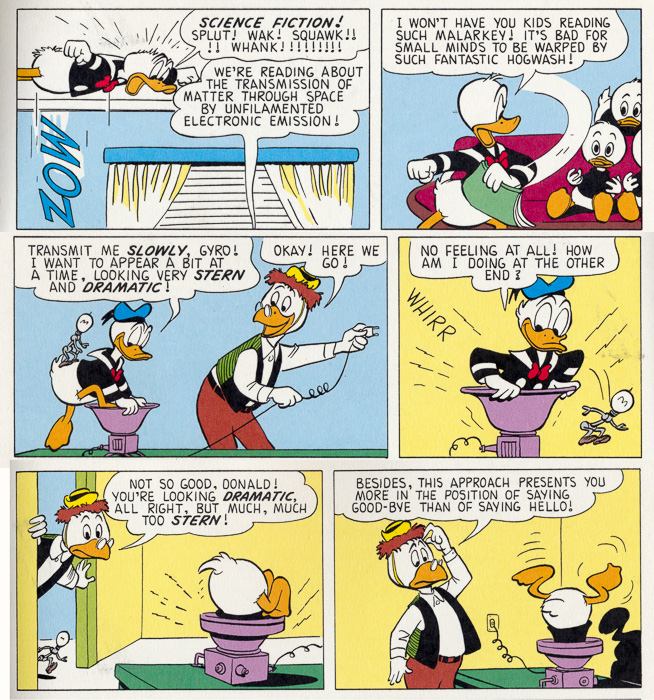

This describes an experiment with with ChatGPT that I made on Jan 17, 2024. I mention “skinks” a lot, so just below, you’ll see a painting of with a bunch of skinks; they’re the guys in the center. I’m writing about a couple named Oliver and Carol, and about their adventures with two skinks named Jenna and Kanka. The skinks who have unexpectedly appeared in San Francisco just a few years from now.

Skink painting entitled “Farmer’s Market.”

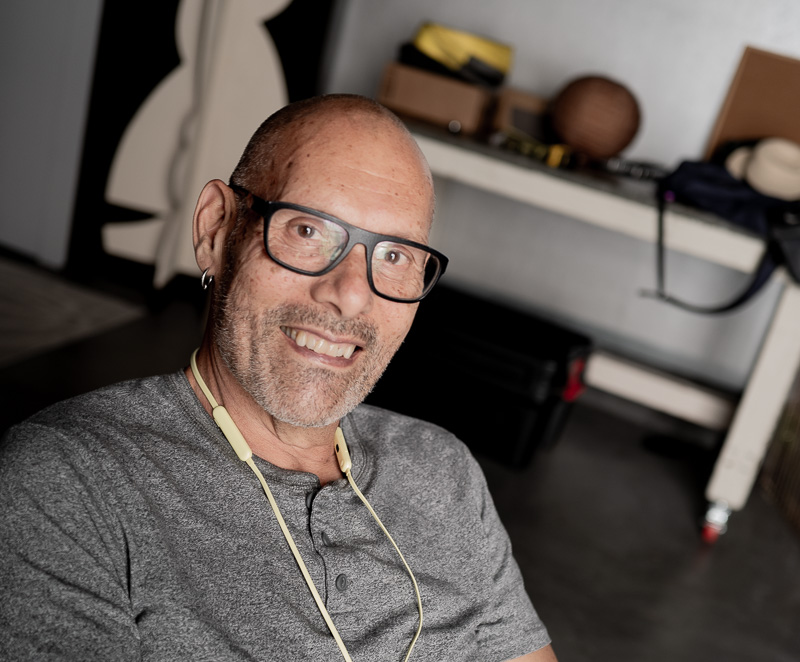

Anyway, I’ve been getting curious about ChatGPT, so I finally went online and gave ChaGPT 4.0 a try. I was urged on by two of my fellow Computer Science professors from my years at San Jose State: Jon Pearce and Michael Beeson. I took about five hundred words of my novel in progress, and fed the chunk to ChatGPT.

Dr. Pearce advises Dr. Rucker in the Red Room, of Santa Cruz.

A ChatGPT “prompt” can in fact be quite long. So you really can use a chunk of your writing. The passage, which I show, below describes a scene where my characters Oliver and Carol are running away from the SFMOMA museum after these skink friends of theirs have eaten a whole bunch of Andy Warhol paintings.

With painter friend Paul Mavrides, admiring the Warhols.

With painter friend Paul Mavrides, admiring the Warhols.

I’m not yet sure what the title of the novel will be, or if I’ll even finish it. After the the end of my experiment with ChatGPT today, I asked it what the title should be, and based on the passages the app had seen, it made a few suggestions, including: “Skinkland Odyssey,” “Warhol’s Whimsy,” “Skinks in the Canvas,” “Pop Realms,” “Artmover’s Dilemma,” and “Surreal Serendipity,”

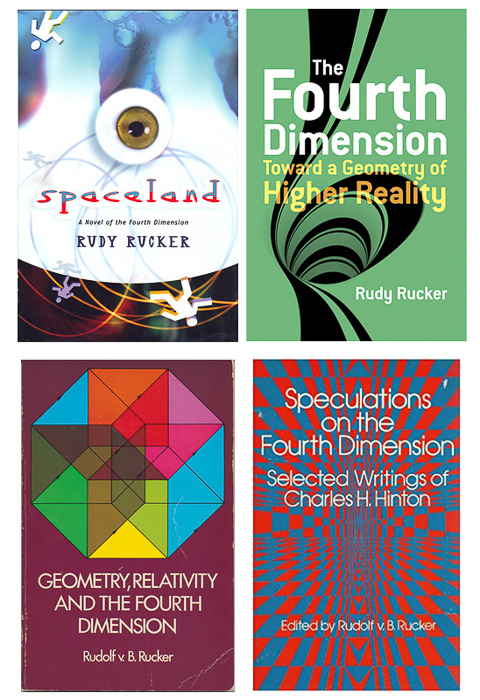

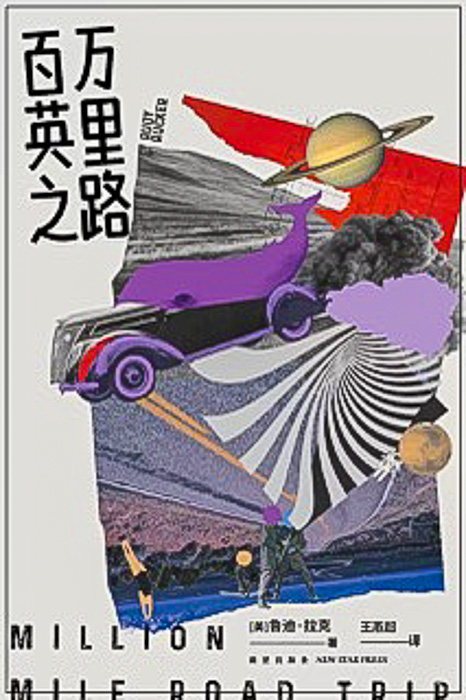

Chinese edition coming out!

Not bad, although none of them is perfect, and as the novel grows, I’ll need a broader title. I wondered if I could feed in all six thousand words of the novel that I have, but ChatGPT doesn’t really like a prompt that’s more than five hundred words. When I tried feeding in all six thousand words, the app crashed, but it did display pretty cool phrase as a label for the crashed conversation. The phrase was “Skinks in Rubber Flight.” Now to me that is a good title, and it’s cool that it comes from a crash, which gives the title a meta and transreal significance.

Frankly I’d been thinking the hype over ChatGPT is a bunch of bullshit. But after this test, I’m staggered and flabbergasted by how well ChatGPT works. As Beeson put it, the method of “choose the next word based on the odds” seems, on the face of it, like a pedestrian and uninteresting approach. . But now—presumably thanks to the size of the vast neural net large language model that is in use—it’s undergone a phase transition.

And by large language model, or LLM, I mean an immense simulated neural net that was evolved by Earth’s mightiest computers. The net consists of a zillion nodes with numerical weights along the lines connecting the nodes. Nobody understands, or can understand, the meaning of the individual weights. As Kurt Gödel proved back around 1930, understanding these weights is, even in principle, impossible. But our tech titans calculated the weights by a somewhat opaque process of simulated evolution.

As a proud writer, I assumed ChatGPT could never write anything colorful or interesting. That it could only churn out bland pap akin to political speeches. But, no, the writing isn’t bad, and it’s got originality, and a bit of verve. Although still, I would say, not much humor.

For me, the crushing thing is that, when I went ahead and ran ChatGPT twice in a row, feeding it the same segment of my novel each time…it wrote two utterly distinct continuations. It could go on writing new continuations all day long.

Somehow this is very deflating. It makes the ground shift beneath my feet.

But I don’t think I’ll often use ChatGPT to help with my fiction! Too much like having a know-it-all full-of-ideas roommate who won’t shut up.

I may yet find a way to get the better of ChatGPT. Some meta parodistic SF trope. Wait till the new novel’s done. Not that, as I say, I’ll use ChatGPT to write it. For now, for sanity’s sake, I’ll return to scorning it from afar. Bitter mockery from the soon-to-be-laid-off craftsman.

You’ll find me alone with my word processor in the coffee shop or my home office or my living room couch or the town library, same as usual. What else can I do?

Daughter Isabel’s jewelry saw

Rudy’s Prompt

Extend this passage in the style of Rudy Rucker. (Note that the following is the most recent a part of the novel I’m writing, and that I pasted this right into the prompt.)

The hall is glass on one side, with a patio out there. We’ve reached a side door. Our skinks snout the doors open. It’s a nook with no exit, a dead end, but whoops we’re rising into the rainy city sky.

Up.

“Hard to hold on,” I wail and, as if understanding me, Kanka enlarges himself and tightens the gaps between his segments, forming a rubbery arc. Like a tyke’s bouncy caterpillar toy and, yes, Jenna has done the same for Carol.

We’re low above the city, not much higher than the buildings, rain pattering into our faces. We’ll need new clothes again. Assuming we make it back to the Box Farm instead of being whisked off to Skinkland or some such. No emergency helicopters in sight as yet. A plus.

The skinks are happy and fooling around, flying circles around each other, comfortably full of chewed Warhol masterpieces. What would Andy think? He wouldn’t like it. What artist would?

We’re flying side by side, slower than before, away from the buildings, right down near the water of the bay. Essentially invisible. Not especially feeling any good luck. I can see the Box Farm.

“Wait!” exclaims Carol. I’m noticing that she says that a lot. She hammers on the side of Jenna’s rubbery bod. “Stop flying. I want to talk to you two.”

“Give us nice dry clothes,” I tell the skinks. “Just switch them out. With waterproof yellow rain gear and waterproof hats.”

“Not yellow,” says Carol. “Gray. Secret mission. We’re going back to the museum.”

My clothes shift and crawl. I’m dry. And not quite cozy yet, by getting there. The rain patters on my impermeable yellow oilskins. I feel my head. The top hat is still in place. Glad for that. My personal logo. Like the villain in a superhero comic.

Carol’s got the gray gear, in a fashionable cut, and a big-brimmed waterproof high-fashion beach hat.

“Topper and Lady Gray,” I say.

“What?” goes Carol. “Never mind. The plan, Oll, the plan. We go back and replace the Warhols. The skinks can grow new ones. The old ones they ate—those are like Flybuzz prompts.”

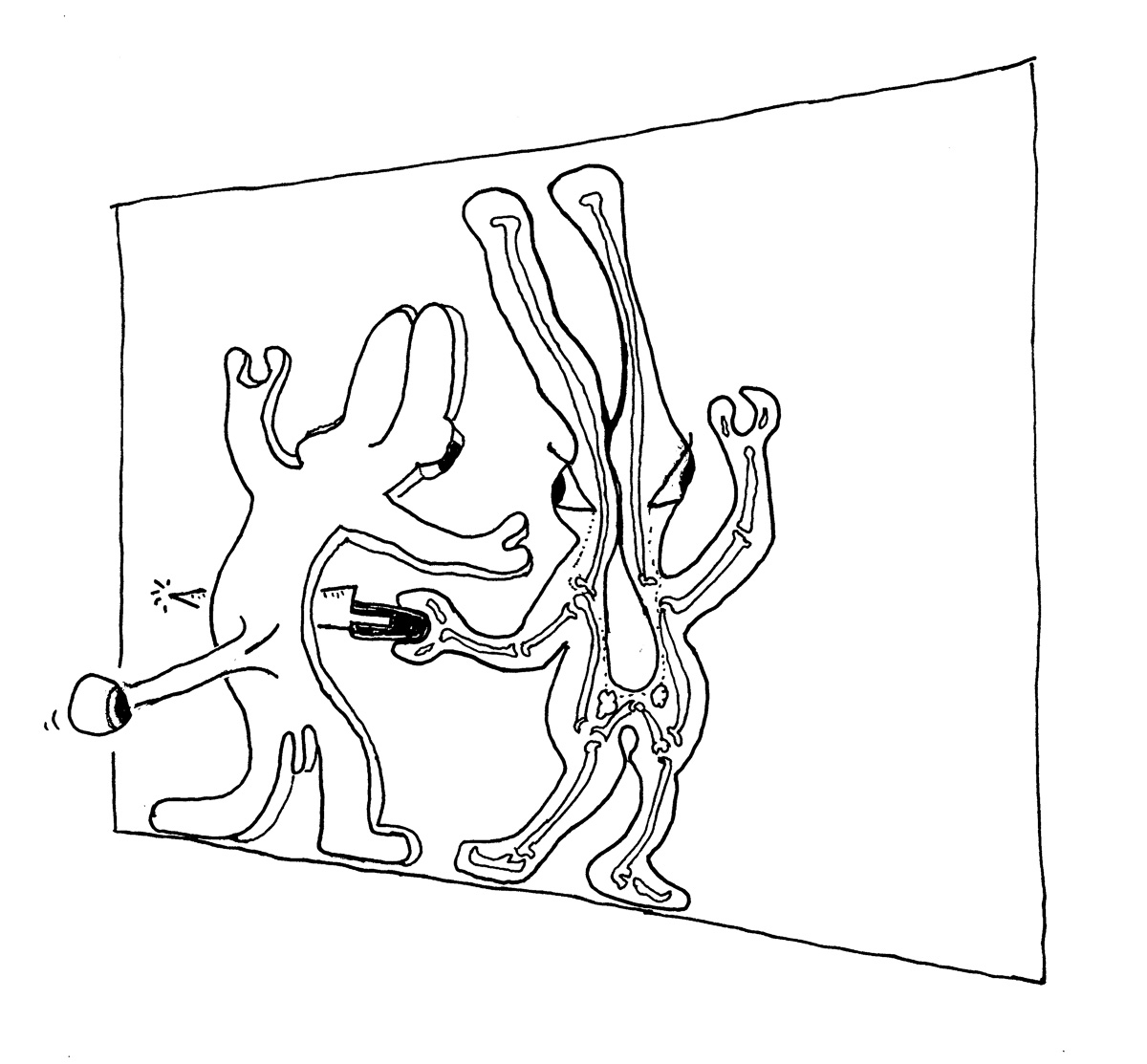

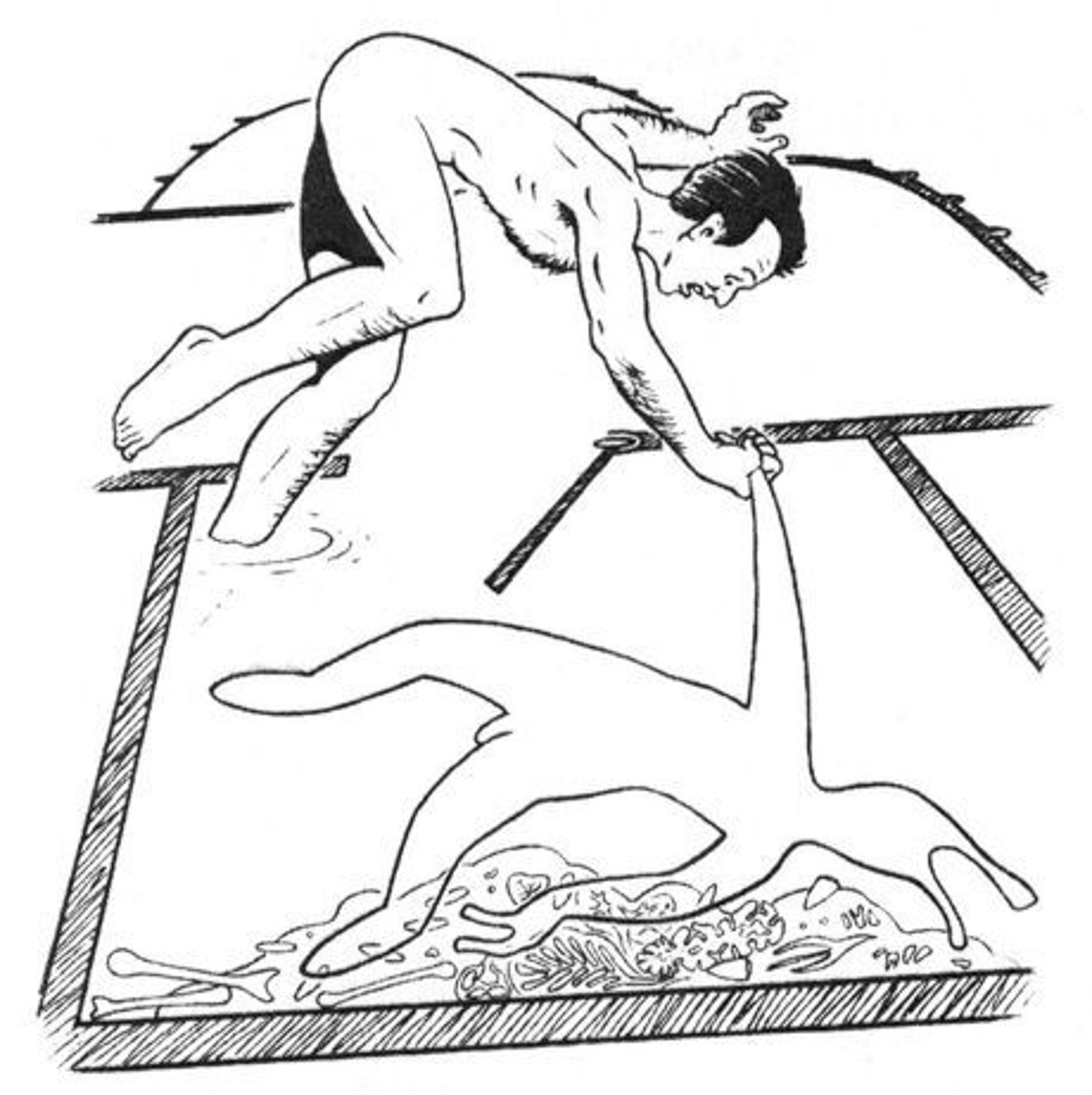

“Hello Infinity”. I drew this while studying higher infinities for Math Ph.D. in grad school at Rutgers, around 1970.

The skinks chirp and twitter, digging on this idea. Somehow Carol understands them. I don’t. Face it, I’m full-on deaf and senile. No use even taking to me, most of the time.

“What?” I say.

ChatGPT Continuation Run One

[So now, the rest of this post is completely fiction written by frikkin’ ChatGPT. Can hardly believe this.]

“Oll, you’re hopeless,” Carol mutters, rolling her eyes at my perpetual state of confusion. “Never mind. The skinks are on board with the plan. We’ll get those Warhols back where they belong.”

The Carol character is to some extent modeled on my Sylvia.

Our skinks, now wearing their own waterproof gear, emit a series of enthusiastic chirps, indicating their readiness for this peculiar mission. As we descend towards the Box Farm, I can’t help but marvel at the rain-soaked city below, its shimmering lights diffused through the falling droplets. The landscape is a canvas of reflections, a Rudy Rucker dreamscape.

Back at the Box Farm, we find ourselves in the familiar workshop, surrounded by the comforting hum of machinery. The skinks, with a strange kind of precision, begin regurgitating Warhol-inspired artworks. It’s an odd blend of the avant-garde and reptilian creativity, a surreal manifestation of collaborative artistry.

“Now, Carol,” I say, trying to focus on the task at hand, “how do we get them back to the museum?”

She holds up a device resembling a cross between a walkie-talkie and a psychedelic kaleidoscope. “This is the Artmover 3000,” she declares. “It creates a temporal fold, allowing us to transport these artworks back to their rightful place without anyone noticing.”

I nod, pretending to understand the intricacies of temporal folds. Carol activates the device, and a shimmering portal appears before us. The skinks, now wearing tiny time-traveler goggles, gleefully carry the Warhols through the portal.

“Follow me, Oll,” Carol says, leading the way into the temporal fold. As we step through, the familiar sensation of being stretched and compressed envelops us. We emerge on the quiet outskirts of the museum, unseen and unnoticed.

Carol takes a deep breath, her eyes gleaming with a mischievous spark. “Let’s hang these Warhols back where they belong and leave the art world none the wiser.”

And so, with skinks in tow, we embark on our surreptitious art restoration mission, a quirky adventure in the rain-soaked city of dreams.

The museum, now shrouded in the quiet hum of the temporal fold, is eerily tranquil. Carol, Jenna, Kanka, and I sneak through the shadows, blending into the backdrop of exhibits. The skinks, their time-traveler goggles gleaming in the low light, carry the regurgitated Warhols with an air of reptilian pride.

“Quietly now,” Carol whispers, gesturing towards the wall adorned with the vacant frames that once held the iconic artworks. We approach the blank spaces, and with the stealth of conspirators in a cosmic caper, we hang the Warhols back in their designated spots. The skinks chirp in what seems like approval.

As we step back to admire our handiwork, a sudden flicker in the air catches my attention. The temporal fold reappears, pulsating with energy. Out steps a trio of beings that can only be described as futuristic art curators—floating entities adorned in chromatic robes, their faces obscured by holographic masks.

“We are the Aesthernauts,” one of them declares in a melodious voice that resonates with echoes of the far future. “We’ve detected a temporal disturbance in the art continuum. What manner of beings are you, meddling with the fabric of creative expression?”

Carol, undeterred, steps forward confidently. “We’re just ensuring that these Warhols find their way home. No harm done.”

The Aesthernauts exchange glances, their holographic masks displaying intricate patterns of abstract art. After a moment of silent contemplation, they nod in unison.

“Very well, art dwellers. Your intentions seem pure. We shall allow this temporal anomaly to close, but be warned—tampering with the art continuum has consequences.”

As the Aesthernauts step back into the temporal fold, it collapses behind them, leaving us in the quiet embrace of the museum. Carol turns to me, a mischievous grin on her face.

“We did it, Oll. The Warhols are back, and the Aesthernauts have granted us their surreal blessing. Another triumph for Topper and Lady Gray.”

And so, in the enigmatic halls of the museum, amidst the echoes of the temporal fold, our unlikely quartet celebrates a victory that blurs the boundaries between reality and Rudy Rucker’s whimsical imagination.

As we revel in our victorious return of the Warhols, a new twist unfolds within the museum’s surreal corridors. The Aesthernauts’ presence has left an indelible mark on the space-time fabric, causing the artwork to come alive with pulsating energy. The once-static Warhols now exhibit dynamic, animated scenes—Warholian visions that stretch the boundaries of reality.

Jenna, always the inquisitive skink, nudges one of the artworks with her snout, and to our amazement, the scene within the frame spills out into the room. We find ourselves amidst a lively, abstract dance of colors and shapes, a living manifestation of Warhol’s pop art philosophy.

“What have we stumbled upon?” I marvel, as Jenna and Kanka join the animated dance, their rubbery bodies undulating in harmony with the vibrant artwork.

Carol, with her newfound ability to understand the skinks, interprets their joyful chirps. “The Aesthernauts have bestowed upon these Warhols a touch of the fourth dimension. They are now windows into alternate realities, portals to worlds only hinted at in the mind of Andy Warhol.”

Excitement courses through us as we explore these dynamic canvases, stepping into one artwork after another. Each frame leads us to a different surreal dimension—a pixelated dreamscape, a neon-lit cyberpunk city, a psychedelic wonderland reminiscent of a cosmic carnival.

However, the Aesthernauts’ warning echoes in the air. Our meddling with the art continuum has consequences, and the boundaries between the real and the surreal begin to blur even further. Time itself becomes fluid within the animated frames, and we find ourselves navigating through Warhol-inspired realms where past, present, and future intertwine.

As we venture deeper into this kaleidoscopic adventure, the line between observer and artwork becomes increasingly blurred. The Aesthernauts’ enigmatic presence lingers, hinting at the possibility of more unpredictable encounters and mind-bending twists in our quest to navigate the ever-shifting tapestry of art and reality.

[And by the way here’s another painting with skinks, I kind of painted them by accident in I think December, 2023, and that’s how all this started. By the way, ChatGPT has the mistaken impression that my skinks are reptiles although, granted, real world skinks are a kind of lizard.]

ChatGPT Continuation Run Two

(So, okay, this is ChatGPT’s second go at extending my story. And this go is completely different! ChatGPT doen’t bother repeating itself. It uses a fresh round of ranom choices and comes up with that’s totally different yet always internally consisten. Like I said, I’m flabbergasted. I heard the hype and I didn’t believe it. But, my dears, it’s true.)

As we soared through the rain-soaked air on our skink steeds, the city lights blurred into a kaleidoscope below us. Carol, clad in her fashionable gray gear, clung to Jenna with a mix of fear and exhilaration. I, in my yellow oilskins, gripped Kanka tightly, my top hat somehow staying put despite the gusting winds.

“Look, Oll!” Carol shouted over the rush of the wind and rain, her voice tinged with a blend of dread and wonder. “The city… it’s like a circuit board, and we’re the rogue electrons!”

I couldn’t help but laugh, the absurdity of the situation mixing with the adrenaline pumping through my veins. The skinks, seeming to sense our mood, accelerated, zipping through the air with a playful agility. Below us, the city was a twinkling grid, indifferent to the bizarre spectacle above.

The two Rudys.

The two Rudys.

As we neared the Box Farm, our destination seemingly chosen by some unspoken agreement, Kanka and Jenna began to circle, descending in a tight spiral. The Box Farm, a cluster of container homes and artistic studios, looked like a geometric puzzle from above, its residents blissfully unaware of the aerial oddity above them.

Landing softly on a flat rooftop, the skinks unfurled their bodies, allowing us to dismount. Carol and I exchanged glances, a silent understanding passing between us. We were partners in this surreal escapade, bonded by the bizarre.

“The Warhols,” I said, breaking the silence. “We need to recreate them. But how?”

Carol looked thoughtful, her eyes reflecting the neon glow of the city. “The skinks ate them, right? So maybe, just maybe, they can… reproduce them?”

It was a wild idea, yet in a night filled with flying lizards and art-eating escapades, it seemed almost plausible. We turned to the skinks, who chirruped in response, their bodies shimmering with an otherworldly glow.

My photographer nephew, Embry Rucker III.

Jenna and Kanka began to contort, their bodies undulating in a mesmerizing dance. Slowly, images started to form on their scales – vibrant, pulsating recreations of the Warhol portraits they had consumed. Each portrait was a perfect replica, yet imbued with a strange, living essence.

Unknown random baby playing in a grill

Unknown random baby playing in a grill

“We need to get these back to the museum,” Carol said, awe in her voice. “But how do we explain this? How do we even begin to return them without causing a bigger scene?”

I pondered for a moment, then an idea struck me. “We don’t explain. We just replace them, silently, like art ninjas. Let the world wonder.”

Grinning, Carol nodded. “Art ninjas. I like that.”

As we began to plan our covert operation, the rain ceased, leaving the city bathed in a serene, misty glow. The skinks, now our unlikely allies in this artistic heist, seemed ready for the next phase of our adventure.

In a world where reality bent and twisted like a Salvador Dali painting, we were about to add our own surreal brushstrokes. Tonight, we weren’t just observers of art; we were its creators, its saviors, its silent guardians. And as the first light of dawn began to creep over the horizon, we set off to restore the Warhols, our hearts racing with the thrill of the unknown.

As we embarked on our mission, the city still slumbered, unaware of the peculiar drama unfolding in its midst. The skinks, with their newly adorned Warhol skins, slithered beside us, a surreal parade marching through the deserted streets. Our footsteps echoed in the empty urban canyons, each step taking us closer to our destination.

[RIP Terry Bisson 1942-2024]

The air was still thick with the aftermath of the rain, a misty haze that seemed to warp the edges of reality. Streetlights flickered, casting long, dancing shadows that played tricks on our eyes. Every sound seemed amplified, from the distant bark of a dog to the soft hiss of the skinks moving alongside us.

“Feels like we’re in a cyberpunk fairy tale,” Carol whispered, her voice barely audible over the sound of our footsteps.

I nodded, feeling the weight of the moment. We were doing more than just returning stolen art; we were stitching the fabric of reality back together, repairing a tear in the mundane world caused by our extraordinary night.

As we approached the museum, the first challenge presented itself: getting inside without alerting anyone. The building loomed before us, a fortress of culture and history. But with Jenna and Kanka, we had more than just brute force on our side; we had the magic of the absurd.

Paintings by Sylvia and by me.

Jenna fluttered up to a second-story window, her body glowing softly in the pre-dawn light. With a gentle nudge, the window swung open, as if welcoming us back. We climbed through, the skinks following silently, their bodies contracting and expanding in an eerie, rhythmic dance.

Inside, the museum was a labyrinth of shadows and echoes. Our footsteps sounded sacrilegious in the hallowed halls, but we pressed on, guided by the faint memory of where the Warhols had once hung.

Reaching the gallery, we set to work. The skinks, understanding our intent, began to shed their Warhol scales, each one a perfect replica of the stolen art. We hung them with care, replacing the lost masterpieces with these bizarre, living replicas. The task was meticulous, demanding our full concentration, but as each portrait found its place, a sense of accomplishment filled the air.

Finally, as the first rays of the sun began to filter through the windows, we stepped back to admire our work. The gallery was restored, the Warhols back in their rightful place, albeit with a secret only we knew.

“Art ninjas indeed,” Carol said, a smile playing on her lips.

We slipped out of the museum as quietly as we had entered, leaving no trace of our presence. The city was waking up, oblivious to the night’s surreal events. As we walked away, the skinks beside us, I couldn’t help but feel that we had touched something beyond the ordinary, a hidden layer of the world where art and magic intertwined.

And as the city came to life around us, I knew that this adventure would forever color our perception of the world. In the ordinary, we had found the extraordinary, and in the mundane, the magical. The skinks, now part of our strange journey, slithered away, disappearing into the waking city, leaving us with memories of a night where reality was not just bent, but joyously broken and beautifully remade.

That’s all, folks!

With painter friend Paul Mavrides, admiring the Warhols.

With painter friend Paul Mavrides, admiring the Warhols.

The two Rudys.

The two Rudys.

Unknown random baby playing in a grill

Unknown random baby playing in a grill