I’m in my home town Louisville, Kentucky, to give a talk at the IdeaFestival 2017. I spoke on the morning of Wednesday, Sept 27, a good crowd, maybe 500 people, the tickets to the event sold out. Here’s a panorama of the audience, shot hastily by me from the stage.

Click for hi-res (but slightly blurry) version.

The final draft of the text and images for my talk is below. My performance differed slighlty from the draft, as I don’t read my talks from a script, and I react to whatever the live audience seems to be picking up on. Working the room, getting laughs, like stand-up.

The slides are online in a PDF here—the slides are just the same as the images in this blog post, only higher-res. As of October, 2018, I have an audio of the talk on Rudy Rucker Podcasts. And KET TV posted a video of the talk (including the Q&A) in October, 2018, as well. I’m having fun at the IdeaFestival. Nice of them to invite me. And it was a good crowd with interesting questions after the talk. Free dinner tonight at a distillery. Party time!

[Musician at a Fellini style beach picnic last week. Honk that horn!]

==========================

“Welcome to Your Cyberpunk Future”

Draft of a talk by Rudy Rucker for IdeaFestival in Louisville, Kentucky, talk given on September 27, 2017.

Where I’m From

I grew up in Louisville, and I graduated from St. Xavier high-school in 1963, not that I’m a Catholic. My father Embry was in fact an Episcopal priest at St. Francis in the Fields. But my parents had the idea that St. X had the best science courses. It’s a good school. But I regret not having gone to high-school with girls. I could have gone to Waggener with my best friend Niles Schoening. He died last year. And my St. X pal Michael Dorris died a few years back. It’s terrible to see your friends and loved ones go. They’re lost. No backup.

Embry Sr, Nonny, Embry Jr, and Rudy in 1957

I left Louisville, and went off to Swarthmore College near Philadelphia, and then I got a Ph. D. in mathematics, and had a career. At this point I’ve published about forty books. Some are popular science books about infinity and about the fourth dimension. But most of my books are science fiction novels. Literary science fiction. Cyberpunk and transreal. Cyberpunk is about computers merging into our reality—and about us maintaining our individuality in the face of that.

Rudy with big brother Embry and his motorcycle in Prospect, Kentucky, in 1981

When I was growing up, I was fascinated by the Beat writers Jack Kerouac and William Burroughs. It helped that my cool big brother Embry had a subscription to Evergreen Review, which is where these guys were publishing. In grad school I was a hippie, and the 1980s, I was a punk. But at the deepest level I’ll always be a beatnik.

Nevertheless I’m a reliable Louisville boy, and a family man, married to my college sweetheart Sylvia for fifty years now, with three children, and five grandchildren.

Our children Rudy Jr, Georgia, and Isabel in Lynchburg, Virginia, 1978. Cyberpunk kids! One of fate’s jokes was to have me live the home of the “Moral Majority” while I was helping to found the cyberpunk movement.

Being a successful writer doesn’t necessarily pay well, so for most of my life I had a day job. I was a math professor until I was forty, and then the family and I moved to California, and I became a computer science professor. I was faking it, but eventually I knew what I was doing, and then I did some work as a programmer as well. And now I’ve been retired for a dozen years. All I do these days is write and paint and put things online.

What is Cyberpunk?

This talk is called, “Welcome to Your Cyberpunk Future.” Your cyberpunk future is here, and you’re in it, and there’s nothing to be scared of. You’re out in the waves, and you can surf. No need to drown. And it’s gonna get gooder.

Back in the day, William Gibson, John Shirley, Bruce Sterling, and I were among the original cyberpunk authors. The word cyberpunk stood for a certain kind of science fiction literature and film, set in the near future. Gibson’s Neuromancer is a modern classic, and everyone’s read it. I’m known for my Ware Tetralogy novels, starting with Software in 1982. And Sterling generated more press than any of us—with his speeches, novels, and journalism. I co-wrote nine stories with Bruce. He can be annoying. A true punk. But the stories came out great.

Transreal Cyberpunk, a collection of stories by Bruce and Rudy. We self-published it last year, and rand a Kickstarter campaign to fund it. Cyberpunk publishing. “Transreal” means writing SF stories that are autobiographical, or in some way reminiscent of the author’s life.

The word cyberpunk isn’t all that well-known. People aren’t sure if it’s good or bad. The strait-laced and repressive forces in our society might reflexively say cyberpunk is bad. But I’m telling you that cyberpunk is good. Cyberpunk is your friend. Cyberpunk is a key to liberation.

The idea behind cyberpunk is simple.

Cyberpunk = Cyber + Punk.

Cyber refers to two things: to people, and to the world that people live in. That is, cyber is about the merging of humans and robots—and cyber is about the physical world mixing with the virtual world of the internet.

One of my paintings . “The Riviera.” In a way, that’s my wife Sylvia and me.

How do people merge with machines? In one direction, we have intelligent programs imitating people. And in the other direction we have people enhancing themselves with devices like smart phones.

Okay, and what about the cyber merger of physical reality and the internet? In one direction, we have computers creating visual effects and virtual realities that resemble our world. And in the other direction our daily world is being augmented by the internet. We spend a lot of time online, and that means the internet is part of the world we walk around in.

Graffiti art at Ocean Beach in San Francisco. A punk diagrammatic crab.

So that’s cyber, now what about punk? In the classic 1980s sense, punk is about sex, drugs, and rock and roll—and about turning your back on conventional rules. As Bruce puts it, “We get in there with spray cans and grunge up those pristine walls.” Cyberpunk literature and film break out of the1970s-type, plastic, white-bread visions of the future. We leave the worlds of Star Trek and Star Wars—and enter the worlds of Bladerunner and The Terminator and Black Mirror.

In the 1980s, when the first cyberpunk novels appeared, a lot of SF novels were about, like, hereditary aristocrats who were colonels in the Space Navy. Some of us had barely escaped being drafted and sent to die in Vietnam. We didn’t want to hear about serving the whims of our so-called leaders. We wanted stories starring people like ourselves. Misfits, artists, stoners, outlaws, women, gays, and people of color. Not officers and cops and rich people.

Punk means countercultural politics. Like, “You’re not my boss. I’m not even listening. I’m doing it my way.”

Even simpler, punk means GTF&WA. Give the finger and walk away.

Software and Wetware

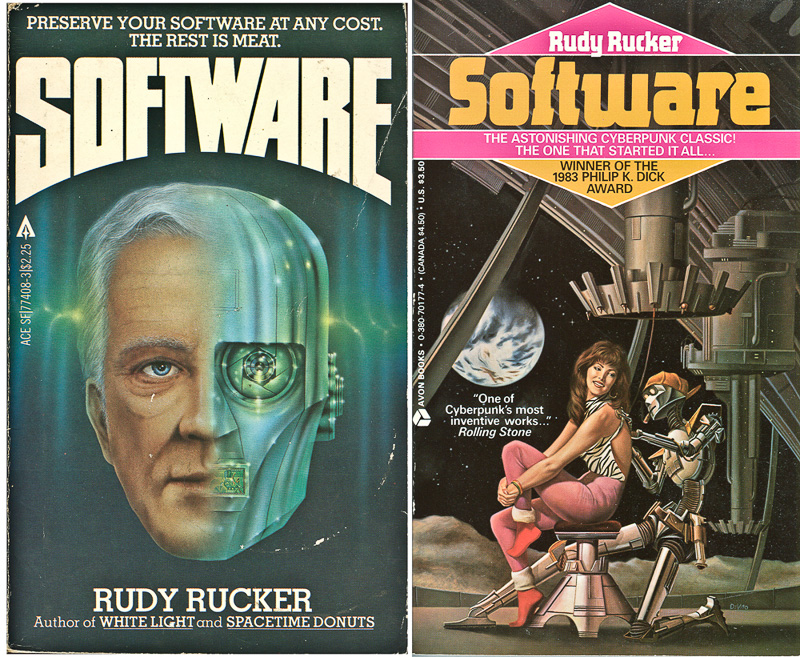

Covers of Software in paperback, (Ace1982 and (Avon 1987).

When I published my novel Software in 1982, the word was almost unkown—I learned about the concept of software by reading Scientific American and by doing post-doctoral academic research on mathematical logic and the philosophy of mind at the University of Heidelberg.

The idea for the novel seems simple now. The idea: It should be possible to extract the patterns stored in a person’s brain, and transfer these onto a robot, and the robot will act just like person. By now you’ve seen this happen in about a hundred movies and TV shows, right? But I was the first one to write about it. In the 1980s, “soul as software” was such an unfamiliar way of thinking that it took me a year to figure it out.

Wetware in the Japanese and the Italian editions.

To make my Software be punk, I made the brain-to-software transfer very gnarly. A gang of scary-funny hillbillies extracted people’s mental software by slicing off the tops of their skulls and eating their brains with cheap steel spoons. One of them is a robot in disguise, and his stomach analyzes the brain tissue. They were based on some people who stayed at the same crummy motel as us one time.

My second Ware novel is called Wetware and it’s set partly in a robot colony on the moon, and partly in my beloved home town, Louisville. In Wetware, the robots get even. They start building people. The idea here is that DNA, or genetic code, is a type of program for your body. And since it’s all slimy down inside your meat, we call this code wetware instead of software. Wetware engineering it going to be huge in the 21st century. Biotech. Genomics.

All the wares are in my Ware Tetralogy. You can buy it or, since I’m a punk, you can get it free. I don’t totally write for money. I write to change the world. I want to infect your mind. It’s a type of self-reproduction!

Cyberpunk Now

The cyberpunk writers of the 1980s were canaries in a coal mine. We predicted the future. We are merging with computers. And our physical world is saturated with the internet. And punks have evolved into slackers and Xers and grungers and hipsters and Y’s and millennials and whatever’s next. But the attitude’s the same. Give the finger and walk away. Punk’s still here. Welcome to your cyberpunk future!

The good news is that the internet turned out much better than anyone could have hoped. It grew and spread before business or the government could shackle it. Why? Because those people who designed it and released it—they were cyberpunks. I’m not saying they were hipsters, no, they were geeks. But they were cyberpunk geeks. They knew about computers, but they didn’t want to obey the elite. They released the internet into the wild, and there’s no way for the controllers to get it back. It’s on the loose for good.

Here’s some of the tasty cyberpunk aspects of the free internet.

*Without getting permission from anyone, you can put up a webpage and you can post pretty much anything you want on it. Free speech.

*You can use the internet to publish your art or your books—both online and in print. Freedom of the press.

*Put a smart phone in your pocket and you’ve got a universal communication device. Talk to anyone anywhere. Use video if you like.

*You’ve got access to the total world library in your pocket.

*You can get a reasonably helpful answer to any question—just by typing it into the search bar.

*You can outsource some of your brain functions. Photos, addresses, directions, dates, calculations—you don’t have to remember them anymore. They’re online, in the cloud.

*Email and the social networks let you hang with a virtual gang of friends all day. A good session on the web can feel like a party. You’re in cyberspace, and you’re not alone.

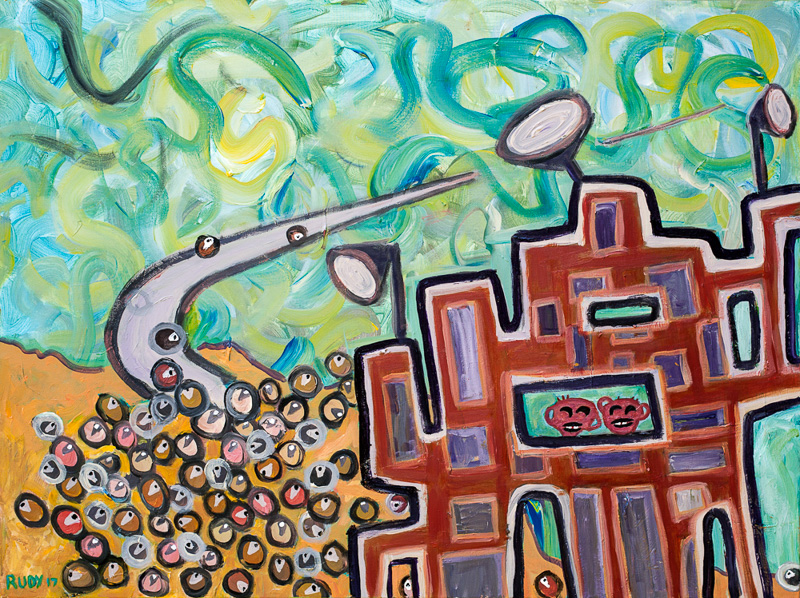

Image of my son Rudy Jr’s ISP Monkeybrains.net. Customers on left.

That’s all good cyber stuff, but we do still need that recalcitrant punk attitude. The browser and social network companies—they’re into building silos of data about you—so pests can pelt you with ads. At the very least, it’s wise to refrain from answering any and all online questionnaires. And never give out your real phone number. GTF&WA.

Even in a democracy, you don’t automatically keep your rights to freedom. You have to win them back, over and over and over again. If you stop being a rebel, they make you a slave.

Cyberpunk Later

Now I’ll mention four possible forms of future cyberpunk tech.

My painting, “My Life in a Nutshell.” How it feels to be using a keyboard all the time! Based on a Philip Guston painting of a guy obsessing over a bottle.

* (1) Smooth interface. Believe me, people are not going to be pecking at tiny smart phone keyboards in ten or twenty years. Voice recognition will finally work. But it’s embarrassing to be talking out loud to your phone, and it’s slow to have to listen to a computer voice.

We might end up with a patch or a soft blob that sits on the back of your neck and communicates directly with your devices, and even with other people. A cell phone that’s kind of glued onto your body, and it can read your brainwaves. As a computer science professor and a programmer, I would, however, advise you that any suggestion of implanting such a device is strongly contraindicated.

Like, “Report to the surgeon for release 2.1.7b?” Nah, external devices are fine.

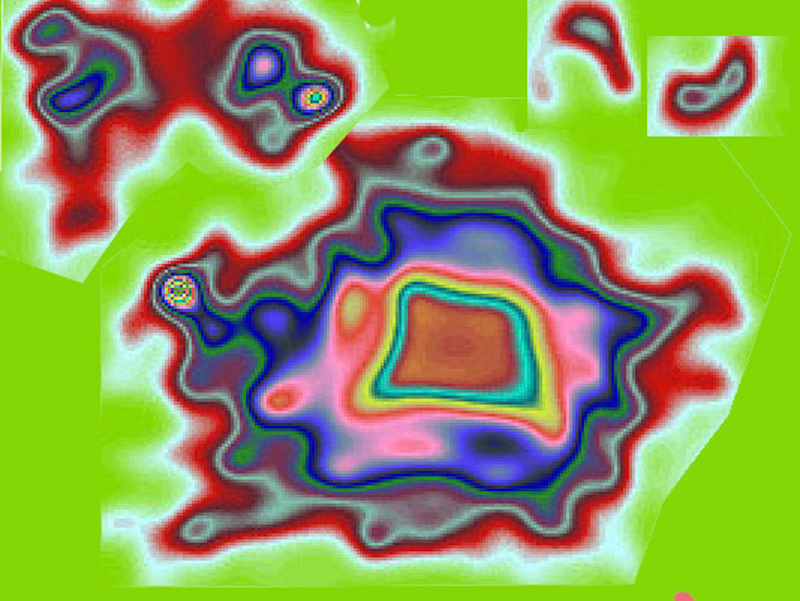

This picture shows a pleasant regress or union you might encounter with telepathy. A yin-yang combo of souls!

* (2) Telepathy. True telepathy might be when, instead of sending information to someone else, you simply send them a link to the location where that information is stored in your own brain. And they can access it there without copying it. Read-only permission of course. And then, relative to you, other people are part of your data cloud.

Here’s my wife Sylvia and me in the digital afterlife. Recorded in Wyoming, 2008.

* (3) Digital Immortality. So how about making a software model of a person? So that, like, I can get my friend Niles Schoening back? In the near term, we already have a simple way for mimicking this process, something that I call lifebox software.

The idea behind a lifebox is get a large and rich data base with a person’s writings, plus videos of them, and recorded interviews. That’s the back end. The front end of a lifebox is an interactive search engine. You ask the lifebox a question, it does a search on the data, and it comes up with a relevant answer.

And for the icing on the cake, add a veneer of AI so the answers fit together into something like a conversation. This will be a huge commercial business soon.

(You can read more about this in my nonfiction book, The Lifebox, the Seashell, and the Soul, online as a webpage.)

* (4) Everything is Alive. The best things in the world are what I like to call gnarly. Gnarl is at the interface between order and randomness. Not all lock-step organized—and not just random scuzz. There’s a whole theory to analyze this. The bottom line is that gnarly processes are, in effect, universal computations that can emulate anything.

Nature is gnarly. Leaves sway in an gnarly, chaotic patterns, never repeating, yet always approximately the same. Water flows in gnarly chaotic motion, too, and flames as well. Chaotic processes form intricately patterned shapes that we call fractals. And of course fractals are gnarly too. Our minds and bodies are gnarly as well. Gnarl is where it’s at.

My point is that any interesting natural process is gnarly, and any such process is, in effect, a universal computer. Even a rock sitting on the ground. A stone is, after all, like a jiggling mass of a septillion atoms, connected by spring-like bonds. There’s a lot happening inside a rock. Why shouldn’t it be as intelligent as I am?

My feeling is that, in some sense, every object is alive—some of the Greeks believed this. They called it hylozoism.

Hylozoism = Matter + Alive

Way down the road, we’re not using manufactured tools anymore. And we’re directly talking to the material objects around us. Because every object is alive.

And how exactly do you talk to the objects? Well, if you’re a hylozoic cyberpunk, you’ll find a way.

(More on this in my essay, “Everything Is Alive” in my Collected Essays, and in my novel Hylozoic.)

Cyberpunk forever!

========================================

(Unused Extra Bit): Nature to Computation to Cyberpunk Art

Water in a creek reflecting the sky

Nature’s processes form intricately patterned shapes that we call fractals. Fractals are gnarly. Chaotic things leave fractal trails.

You don’t fully appreciate the gnarliness of water and of reflections of light until you analyze these with computer models of them. For a cyberpunk, a computer can be a funhouse mirror of the world. A distorting lens to see through.

Computer model of water using my CAPOW software.

The way to profit from our merge with computers is not to say “we’re just computers.” Instead you want to say “computers can be as interesting as us.” Cyber can sound dull, but if you punk it up, it’s gnarly.

Painting of the computer model. I call it “Alien Taxi.” A computer simulation of nature’s chaos inspires a vision of an alien vehicle.

A cyberpunk artist sees unknown new forms.

September 26th, 2017 at 7:01 am

Hi Rudy – This topic is fascinating. (The understatement of the year.) I am going to attend your talk at IdeaFestival tomorrow and I’d love to do a short video interview with you to accompany the article on TechRepublic. Please email me if you’re interested. (I’m also a Louisville native who eventually moved to California. So at least we have that in common.)

October 5th, 2017 at 4:40 pm

Wow. Just fugging wow. I don’t even know where to start. You and Embry on the hog; you just jump off the page — ‘that’s Rudy!’

And the shot of your kids – it should be on your living room wall! And the ‘Riviera’, I just shouted out ‘I bet that’s Sylvia’ then look at the caption: yup, it is.

You could have stopped 20 years ago and would still be a master of your art! Keep it coming, dude, keep it coming.

Love to all of you and yours.

November 7th, 2017 at 5:56 am

Hi Rudy.

I’m trying to write a little novel / experiment kind of cyberpunk topic.

Your work looks really complete around the genre, and maybe you could help me, gime me some advise.

That would very kind.

Thanks and regards.

November 7th, 2017 at 7:43 am

Hi Fernando. I don’t have time to give you personal advice on your writing. But I do have a document called “A Writer’s Toolkit” online, which contains material I’ve used in a would of writers’ workshops. Maybe there’s something in there that’s useful for you. You can find this document (and also files of notes on how I’ve written each of my books) on my Writing page.

http://www.rudyrucker.com/writing/