In London, we rode around a lot in those classic double-decker red buses. Public transportation. They’re better than tour busses—you get up on the high level and you really see a lot. And you’re with the locals. And if you get on the wrong bus, doesn’t matter, you’re still seeing London. One “wrong” bus led me to one of the biggest bookstores in the world: Foyle’s. My old hacker pal John Walker had recommended it to me. Spent a half hour there, comfortable, reading new science books.

I was surprised how crowded London was—I have this nostalgic tendency to think of London as lonely and foggy like in an old black and white movie, with echoing footsteps on the damp pavements. Many of the sidewalks were filled to capacity people—particularly a shopping area like Oxford Street on a weekend. And the subway trains can be as full as in NYC or Tokyo.

Looking up a site about sizes of city-sprawls or “agglomerations,” I later found Tokyo at #1 with 34 million, New York at #10 with 21 million, London at #24 with 13 million people, and San Francisco (including the whole Bay Area, that is, Oakland and San Jose) at #46 with 7 million.

Lots of white people in London—in NYC or the SF Bay Area you don’t see quite as many. And these English white people, they’re really white…they’re, like, the archetype of whiteness. In the US, we’re programmed by decades of Madison Ave propaganda to think of them as the norm, the Platonic ideal. Many of them are indeed very beautiful or handsome.

I saw a lots of pairs of young women going around together, like hunting teams, with, almost invariably, one blonde and one brunette. The bare legs often quite doughy. Tough-looking short-haired pasty-faced guys as well. Many interracial groups.

Many Indians, Africans, Arabs, and West Indians are in London as well—blow-back from the Imperial days. These two West Indian guys were doing a show in a big square at Covent Garden.

The deal with these outdoor shows is that you yell for a really long time, it’s your chance to shine, and maybe your eventual tricks aren’t all that amazing—these guys were leading up to a limbo routine. But the crowd enjoys the shouting, the rhythm, and the simple feeling of being in a horde.

Peaceful in the churches of course. Sleeping sarcophagus people in Westminster Abbey (or is that the leg-weary Rudy and Sylvia in their hotel room.) Westminster an amazing place, one of those tourist attractions that far outstrips expectations, so full of stuff, with so many levels of detail. Like a fractal.

I was ultra-psyched to see Isaac Newton’s grave. Newton! The laws of motion, calculus, the spectrum, gravity—Newton! “He invented calculus?” said Sylvia dubiously. “I don’t think that’s much to be thankful for.” I stood there for awhile, communing with Newton’s big soul. I dug that they had special spot for the graves of scientists, and other spots for artists, and for writers.

Awed and unsure, a woman makes her way past the (replica) sacarphogi in the Victoria and Albert museum. One of those symbols-of-our-daily-life photos.

At one point we managed to attend a church service in Christopher Wren’s St. Paul’s cathedral. I liked sitting there with the lovely, echoing choir music. I was counting things—like the number of panels set into the arches. Odd numbers like 11 and 13. Clever numerical rhythms in the stilled stone.

Studying my guidebook, I’d learned of this seriously old pub on (yes!) Fleet Street called “Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese.” Rebuilt shortly after the Great Fire of London in 1666. Samuel Johnson lived practically next door, and it’s believed (at least by the pub’s aficionados) that Johnson went in there from time to time with Boswell. Like he’d say, “Let’s take a walk on Fleet Street.” Possibly reticent here, as Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese was also, in the old days, a brothel.

The name cracked me up, so we went in there, a windowless place with many nooks and crannies, populated by yuppyish workers from the nearby law courts, dank, echoing, unchanging. Inspired by the Johnson connection, I got Boswell’s “Life of Samuel Johnson” for my Kindle from gutenberg.org, and started reading it every evening. Soothing, mildly amusing.

[Photo above was taken near the way-too-crowded Portobello Road Market on a Saturday in Notting Hill, with two old guys playing John Lee Hooker songs behind the woman checking her phone.]

Another day we stopped by a more congenial pub, the Spread Eagle in Camden Town, with windows, couches and old wooden tables. It was a Sunday, and people were settling in for the afternoon, certainly drinking and laughing, but in a more sociable, slow-paced way than in an American bar. One couple was even playing the Jenga stacking game—the pub had a stack of games behind one of the couches. Like a lodge, kind of. Or a shared living-room. Albeit with a large puddle of questionable liquid on the floor outside the basement bathrooms—a bit manky, that. Even so, I’d happily frequent the Spread Eagle if it were in my neighborhood. You could even sign up to have a convivial Christmas dinner there. And in the evenings—well, I think of James Joyce’s phrase, “shoutmost shoviality.”

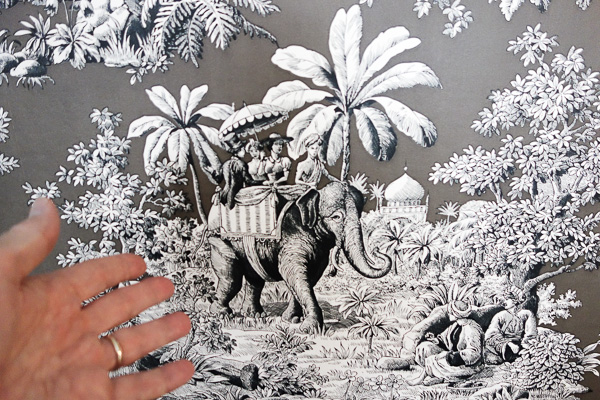

The wallpaper in our hotel bedroom had elephants on it. Back in the day, the sun never set on the British Empire, right?

And the nice lady guard at Buckingham Palace holds a machine gun.