I’ve been writing a lot lately, working on my novel The Big Aha, and on a short story called “Apricot Lane.” I also gave a guest lecture at UC Berkeley and participated in a workshop at the Institute for the Future in Palo Alto. In today’s post, I’ll catch up on some of this.

In The Big Aha I have these two mysterious spheres kicking around, about the size of softballs. They’re called the oddball and the dollshead, although their actual names might be Alef and Zeee.

They’re otherworldly beings of some kind, and in the books’ final chapters they’ll transfer one or two of my characters to a higher world for some extra adventures. This is a standard move from the Monomyth or Hero’s Journey pattern, which was famously described in Joseph Campbell’s The Hero With A Thousand Faces. (Note that, with a few tweaks, you can get a variation on the pattern that works for a Heroine’s Journey as well.)

As I sometimes do when I’m stalled or unsure in a novel, I did a painting of these two beings, and I call it The Two Gods.

“The Two Gods,” oil on canvas, March, 2013, 24” x 324”. Click for a larger version of the image.

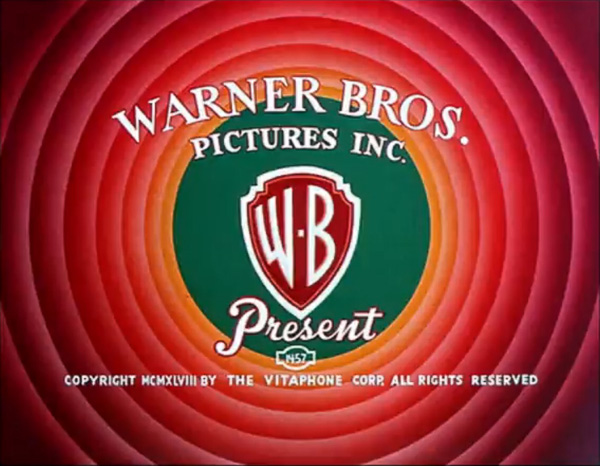

They’re like lizards, a little bit, with long tails going off into the beyond. I posted a little about my plans for the oddball before on February 5, 2013, in “The Bogosity Generator Tool in Science Fiction,” and when I wrote that post I was thinking about trying to basing my painting “The Two Gods,” on the start sequence seen in Warner Brothers cartoons of the Merrie Melodies or Loony Toons ilk.

On the art front, my show is still hanging at Borderlands Café on Valencia Street in San Francisco. It’ll be up until March 27, 2013, and I have a video of the show below. I marked the prices of my paintings way down for the show, and I’ve sold four in the last month. More info on my Paintings Page.

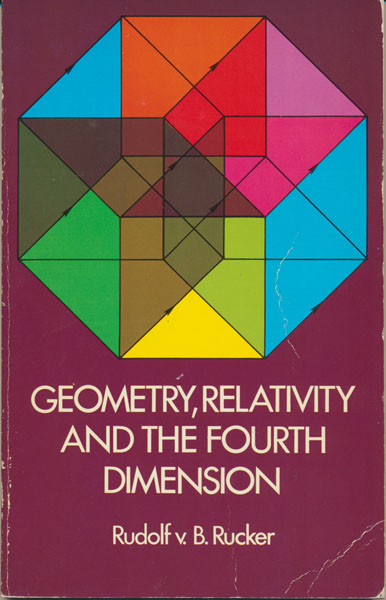

Rolling back to earlier this month, as I mentioned, I gave a talk on the fourth dimension at Alan Weinstein’s math class at UC Berkeley. The class is using my very first book as their text, Geometry, Relativity and the Fourth Dimension (Dover Publications, 1977). Incredibly this little book is in its seventeenth printing, with over a hundred thousand copies sold.

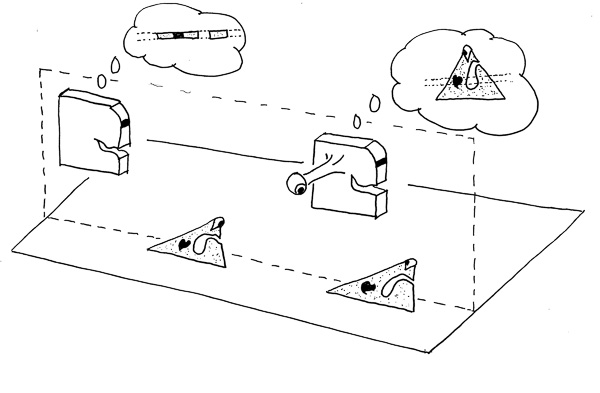

Above is a scan of one of my older copies. For the class I got into some illos from my novel on the fourth dimension, that is, Spaceland, which was inspired by Edwin Abbott’s 1884 novel Flatland .

Flatland describes higher dimensions in terms of a two dimensional square being, A Square, shown above in my painting of the square and his wife, who is a line segment. In the novel Flatland, A Square is lifted into the third dimension, and gets a view of our world as seen from a higher dimension. There’s a few issues that come up here. If you tug A Square up into 3D space, do his innards spill out? And how can his flat eye with its 1D retina see much of anything in 3D?

I got into these issues in my novel Spaceland. My solution was that, before a 4D being tugs my hero Joe Cube up into 4D space, Joe is “augmented,” that is, he’s given a bit of a 4D hyperthickness, his upper “side” is sealed off with new skin, and he grows himself a hyperdimensional extra eye that projects out into hyperspace from the center of his brain.

The rather complex image shown above depicts these moves in terms of A Square, up in the higher (3D) space looking down at his father, who is a triangle. If the Square tries to use his normal eye, he only sees a 1D cross section of his father. He needs that higher-D eye to get full 2D images on his retina so he can form mental images of 3D objects.

In the same sense, if you try and use your normal eye to see in 4D space, you’ll only see 2D cross sections of things. And what you want is to have a 4D eye with a 3D retina, so you can look at, like a person, and see all of their inner organs at once. Like the way you see your house in your mind, with every closet and drawer open to your inspection.

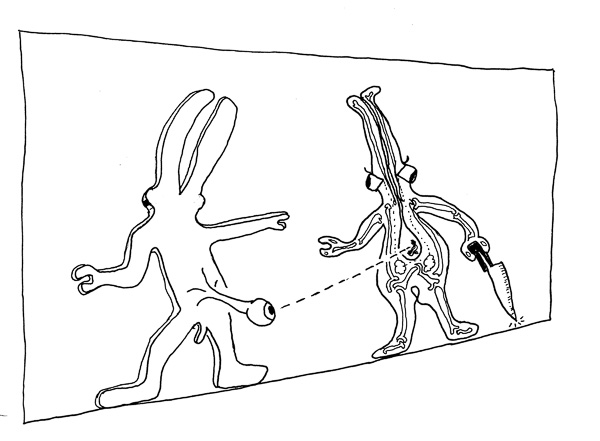

A little more fun with the higher-dimensional eye. Suppose that the Flatland creatures aren’t simple squares, but are more like organisms with bones and a stomach. Suppose that “Dad” here has been augmented with some thickness and with a higher dimensional eye. So he can see that flat “Mom” is hiding a knife behind her back.

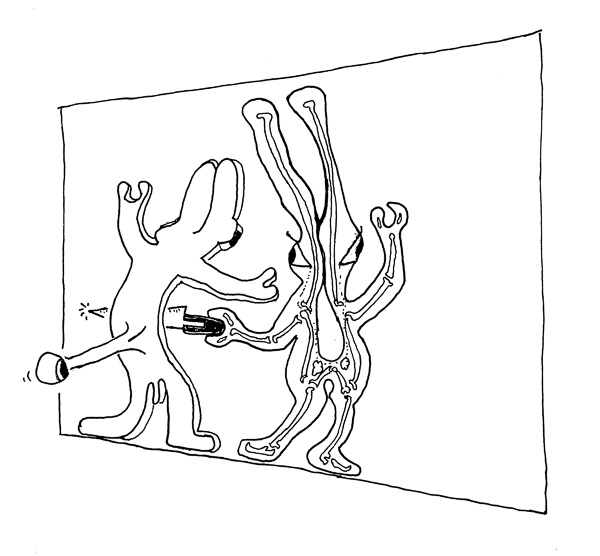

Mom makes her move, but Dad bulges his belly out into a higher dimension!

I always go check out Telegraph Avenue when I’m in Berzerkistan. Been doing that for forty years. These days the Ave is at a bit of a low ebb. The epic Cody’s bookstore is gone, indeed all four corners of that block are deserted, and, at least on the day I visited, the street denizens seemed to have arranged a pair of trucks so as wall off access to People’s Park. Note the edited street sign.

At least Rasputin’s and Amoeba record stores are still there, not that they’re very flush. All kinds of media stores are fading away…books, CDs, DVDs…all dissolved in the digital torrent.

I’m a bit of a connoisseur of images of the Pig Chef—that traitorous being who delights in slaughtering, cooking and devouring his peers—and I saw this well-executed Pig Chef on a truck by People’s Park. If you’ve never read it, do check out my Pig Chef story, “The Men in the Back Room at the Country Club” in my online Complete Stories. Not to give too much away, in my tale, the Pig Chef is a Sta-Hi-type character who ends up BBQ-ing people and feeding them to alien preying mantises…

Another thing I did recently was to attend Institute For The Future workshop on the theme of objects joining the internet. See the IFTF post on “The Coming Age of Networked Matter.” My host was David Pescovitz, who also does some work at IFTF.

IFTF has commissioned me to write a short SF story on networked matter, the story to appear for free on Boing Boing and in other spots—it’ll be Creative Commons licensed. Madeline Ashby, Cory Doctorow, Warren Ellis will be writing stories as well. For now I’m calling my story “Apricot Lane,” and that’s what I’m working on right now.

I wrote about a rather enjoyable world with tagged and even “living” objects in my novels Postsingular and its sequel Hylozoic. And note that a free CC version of Postsingular exists.

But this time around, for the purposes of “Apricot Lane,” I’m thinking that it wouldn’t necessarily be pleasant if the objects around you could talk to you or exchange information with you.

Thinking along these lines, I remembered the “dogsh*t day” scene in Phil Dick’s novel A Scanner Darkly. Bob Arctor’s car has malfunctioned. He’s pulled over at the side of a freeway with his freaky and possibly evil friend Barris. He’s hallucinating that his engine block is smeared with dog crap, and Barris somehow knows this and is teasing Arctor, smiling at him from behind his mirrorshades. And then Arctor starts to hear the parts of the engine talking to him and he throws up.

He felt, in his head, loud voices singing: terrible, as if the reality around him had gone sour. … The smell of Barris still smiling overpowered Bob Arctor, and he heaved onto the dashboard of his own car. A thousand little voices tinkled up at him, shining at him, and the smell receded finally. A thousand little voices crying out their strangeness; he did not understand them, but at least he could see, and the smell was going away.

Good old Phil.