Rudy and Cory Doctorow reading SF stories, for about a half hour each, starting at 7:15 on Wednesday, May 16. Readings followed by Q&A discussion. This is a kick-off for phase 2 of Terry Bisson’s “SF in SF” series, now sponsored by Tachyon Books. It’s at a new venue: VARIETY THEATRE at 582 Market St, San Francisco. Cash bar.

Author Archive

Rucker and Doctorow, SF in SF

Friday, March 30th, 2007Vlogging and Panpsychism at Dorkbot SF

Friday, March 30th, 2007Rudy presents at the monthly San Francisco Dorkbot meeting, held at 3359 Cesar Chavez Str. at Mission St, starting at 7:30. Others will give some short presentations as well. There’s a cash bar and maybe even food. Rudy will talking about some of his recent ideas about the distant future, including extreme forms of videoblogging plus his (unrelated) notion of quantum computational psipunk panpsychism (or hylozoism), whereby every object is alive.

Missing Gnarl. Peng Parasims.

Wednesday, March 28th, 2007Here’s today’s idea for Hylozoic, second volume in my forthcoming cyberpunk trilogy. Having written chapter one, I’m reworking the outline. Dig this, dear reader.

The Missing Gnarl. This is where I want to end up: the birdlike alien Peng are siphoning off the gnarly computation from Earth’s matter. As a result, our clouds, waves, fire, wind, plants and minds behave more simply. What are the Peng using the gnarl for, and how are they stealing it?

[Me with my friend Gary on the roof the SF Opera house after he gave us a backstage tour after the ballet on Sunday. Scanning the sky for UFOs.]

The Peng use the missing gnarl to simulate individual Peng that thereby acquire a physical presence on Earth. These “parasims” are much stronger form of emulation than a simulation that lives within a virtual reality. Parasims have mass and physical presence. They’re the output of a heavy-duty distributed quantum computation spanning the decillion or so particles on the parasims’ “ranch.” The parasim Peng fall apart without a steady influx of computation. They’re like ice-sculptures in a blast furnace, being kept together by a zillion gnats with trowels and Slushy cones.

[At the opera there’s a prop area with for instance every kind of staff they might need for staging a show. People use staves a lot in opera-land. Keeping the actorly persona together like a parasim.]

Here’s the kicker. Due to certain inefficiencies of the emulation procedure, maintaining the physical presence of a single Peng family’s parasims requires every bit of the gnarly computation contained within a patch that covers some ten thousand square kilometers of Earth’s surface. That’s a million hectares. Putting it another way, parasimulating a small Peng family requires the resources of Peng ranch which is a square that’s roughly sixty miles on a side, like a large county. And the parasims soak up the computation in a mile of the air above the Peng ranch as well as a mile’s worth of the Earth’s crust below.

[The Los Gatos fountain wouldn’t look like this anymore. It’d be simple parabolic arcs.]

A Peng has to be very wealthy to become an Earth-based parasim. It’s the final big pay-off for a prosperous Peng life, it’s like immortality. Our Earth is like a heaven for the Peng. Although their planet Penga is forested, it’s a cooled-off, senescent, uninteresting world—like the Peng civilization itself. Earth is a Pengese post-retirement paradise. We marginalized humans are like natives bitterly squinting at a McMansion development that takes up most of our island.

[We’ll still have our bakery, but all the shapes will be perfectly simple and smooth. It’ll be hard to mix things with no chaos or gnarl working for you.]

Talk about conspicuous consumption! Huge areas of Earth are to be drained of interest to support a few smelly, pecking Peng. There’s just the one dot of bright, happy Peng gnarly amid a million hectares of dullness.

How many Peng does Earth have room for? Suppose the Peng want to live on land, not water. Earth’s surface has 150 million square kilometers of land, that is, 1.5 * 10^8 square kilometers. And I’m supposing that a Peng (or a small Peng family) requires the computational resources of a land area that’s a hundred kilometers by a hundred kilometers, a Peng ranch of, once again, 10^4 square kilometers. Doing the math, on Earth’s whole land surface we’d have room for some fifteen thousand Peng ranches. Only the cream of Pengese society need apply! Announcing the Wigfalls of West Philadelphia! Assuming the Peng won’t be moving into the intrinsically dull zones, Earth’s developers will only have room for maybe five to ten thousand Peng ranches.

Wow. I’m thinking of some great possibilities here. Peng realtors! Sell-out Earth developers!

Dot Patterns for Birthday Cards

Friday, March 23rd, 2007So yesterday was my 61st birthday. I had some fun getting out the trusty old ruler and compass and making a Pythagorean-style pattern with 61 dots. Note that it consists of six “tetractys” patterns whirling around a central dot. Tetractys was what the Pythagoreans called the familiar bowling-alley pattern of 1+2+3+4. One can also speak of 61 as a hexagonal number.

I figured all this stuff out in 1985 and 1986; that is, how to represent many of the “birthday numbers” (from 1 – 100) as nice patterns of dots. I uploaded a very useful file about this for the world today:

Dot Patterns for Birthday Cards

[The file is the Adobe Reader PDF format; I found that with my latest version of Firefox, I needed to install the new free Adobe Reader 8.0.]

The material is drawn from my book MIND TOOLS: The Five Levels of Mathematical Reality (Houghton Mifflin, Boston 1987). Twenty years ago! I think it’s out of print but there’s used copies on Amazon.

For the last twenty years, I’ve been putting these dot patterns on almost every birthday card I’ve signed—and now you can do it too!

By the way, you’ll notice that some numbers don’t seem to have any nice dot patterns. For these difficult birthdays (or anniversaries), I turn to Plan B:

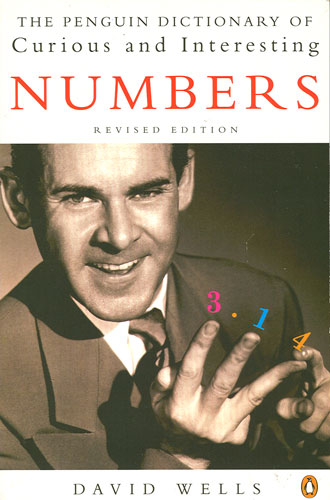

David Wells, The Penguin Dictionary of Curious and Interesting Numbers.

(I always get a chuckle out the picture on the cover because the guy looks like such a complete pinhead.)

This valuable, nay, indispensable book has an entry for—well, not all—but lots of numbers. Though, let it be said, many of the entries describe properties that are not exactly box-office gold. Like, “1/61 has decimal period 60 which includes 6 occurrences of each of the digits 0 to 9, the smallest reciprocal whose period has this property.”

The Mathematician Godfather makes you an offer you can’t understand… The virtue of my Dot Patterns for Birthday Cards is that most of them are visual patterns you can readily fasten onto. Patterns for a cheerful, uncomplicated Birthday Pig.

By the way, I first heard about Wells’s book from the mathematician Richard Guy when I jokingly asked him what, in his opinion, was the first uninteresting number. He said it would the first number I would not find in the Penguin Dictionary of Curious and Interesting Numbers.

The reason my question wasn’t entirely serious is that asking about the first uninteresting number poses a paradox (related to the Berry Paradox in the philosophy of mathematics). For the first uninteresting number is, hmm, kind of interesting.

Wells, too, is aware of the paradox, and he lists 51 as being the first number with no interesting properties, and duly notes that this makes it interesting.

The first number so truly dull that Wells doesn’t even list it all is—drum roll—54. But if you’re 54, don’t despair. It’s meta-interesting!