A crazy new SF adventure…with entitled realtors from the infinite subdimensions.

So my last novel Juicy Ghosts is out there, and I’ve been idle for a few months, so now—what to do? Nescio. That’s Latin for “I don’t know, son.” Don’t know what I’ll write next, don’t know if I’ll ever write again. But I’ll start groping. As usual, most the photos in my post have no direct connections to the text.

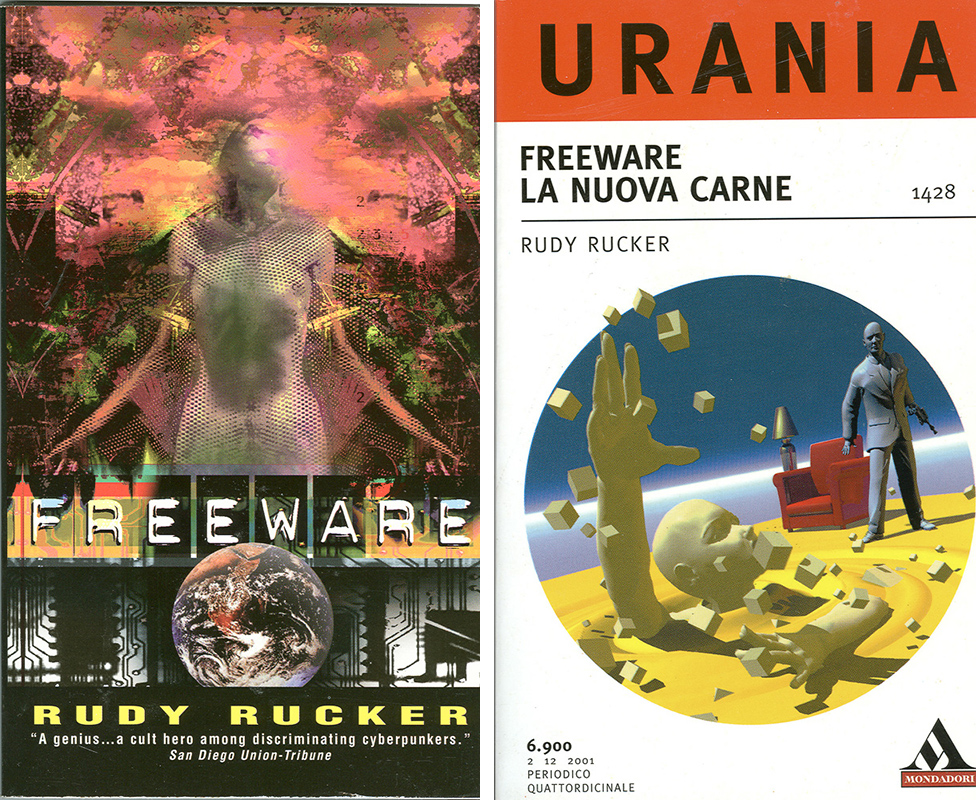

In 2019 I did some work on a story that I called “Everything Is Everything.” I finished a draft of it, couldn’t sell it to any mainstream SF Zine, and a second draft appeared in the underground zine, Big Echo in October, 2020. I’ll be posting a third version on my blog soon. I’m opening it up a little so that it can lead to lead to a larger adventure. Mabye a novel. I’m on the verge of a Chapter Two.

It’s like the way that Juicy Ghosts started out as a single short story, and then I wrote a couple more related stories, and then they stuck together and grew out more material to make a novel. “Everything Is Everything” might be like that. I hope so.

So now, by way getting going on the next phase of “Everything Is Everything,” I’ll review some of the notes I made when I was working on the ideas back in 2019 and 2020.

Recurring Dreams

Sometimes, as I’m falling asleep, in a liminal state, bobbing up and down beneath the surface of sleep, I’ll feel myself sliding into a dream situation that seems familiar. A background is in place, with familiar scenery, and established characters, and a situation, and I have a sense of knowing a history of what’s going on. What would be the word for this. Not really dejà vu, as in “I saw this before.” More like dejà revé. “I dreamed this before.”

When I encounter a seemingly familiar dream, I may drift back towards the surface— and then sleepily wonder what’s the cause of my remembering the dream from before. I see two options.

Illusion. In one fell swoop my dream-mind has created a new stage setting, including a sense of having seen it before.

Recurrence. The setting is a fragment of a recent dream. The setting was latently present in my subconscious, and it seems familiar because it is familiar.

The “recurrence” option feels more accurate, as I do at these times have such a clear sense of the scenario having a history, and that I’ve been in the scene before, and it seems like wouldn’t “have time” to invent all of that background-prior-dreaming on the spot. This said, the “illusion” option is viable. Sometimes my busy mental dream machine might fill in fake histories along with its fake scenes. Why not?

This said, there are cases of repeated dreams, like portentous repeated nightmares as in a pulp novel, and this kind of dream is something that you remember and brood over when illusion you’re awake the next day, and then you go back to bed and have that same dream again.

But the maybe-maybe-not repeat dreams particularly important or epic dreams, and you don’t happen to remember them when you’re awake. Even if you have them night after night, each time with an increasingly dense sense of prior history.

Absolute Continuum

In a different vein, I want to write about my kick: we live in an Absolute Continuum. I sampled this rich vein of ore in my story “Jack and the Aktuals.” But in that story I didn’t go the whole hog, that is, in “Jack and the Aktuals” I didn’t fanatically insist that our actual, waking-life cosmos is an Absolute Continuum.

I do claim this in my new preface to the fifth edition of my best-selling non-fiction book, Infinity and the Mind. I’m old and respected (or ignored?) enough now that I can write prefaces that are close to being certifiably insane.

And now I want to put this idea into my “Everything Is Everything” story.

Dream Work

In a recent “repeat” dream, I’m living in a rooming-house and working as a salesman—and I know things about the other tenants.

I see a fantasy-SF-type story here. The guy (or woman) realizes that they’re doing work in their dreams, like as a spammer or telemarketer or focus group or image-recognizer.. It might be nice, if possible, to connect this to a commercial telepathy device, call it a teeper. The guy is . bewildered after his naps. Just like I was after my 45 minute nap on the Santa Cruz Beach the other day, a nap which, by the way, started with a familiar-feeling sensation of returning to a rooming house where I’ve been working long hours of late. I woke unrested. I was tired the rest of the day.

A teeper device that resembles one of those hearing aids—and my guy keeps forgetting to take it off when he sleeps. And then he’s doing dream work in that phantom rooming house visions. I in fact ended up putting a lot of this into my Juicy Ghosts novel, where people get “immortal souls” that are siloed in a big company’s cloud computer, and they are in fact working for the company.

What if my character Wick had has a consulting gig as a napper. And doing dream work.

“What are you doing in these dreams?” asked his wife Vi. “Programming?”

“It’s more like I’m inventing puzzles.” said Wick. “Those quizzes you see when you sign onto some websites? The quizzes are called captchas? They’re mining my thoughts for captcha puzzles.”

“I wouldn’t like that kind of work,” said Vi.

“Right,” said Wick. “My boss is in my head every night. I call him Pigling Bland. He knows this. It’s hard to cover up anything in brain-to-brain conversation. It just comes out. He’s Pigling Bland and he’s a rah-rah middle-management greed-head with no mind. He calls me Space Case.”

But I want something more fantastical for the dream work. Like talking to the dead, or to aliens, or to critters from alef-seven. Or Wick is opening the door to the Absolute Continuum. Like in a fairy tale.

Maybe the aliens are using his dreaming mind as some kind of amplifier.Or a scanner. They’re using us dreamers to “see” or notice stuff they can’t quite resolve. Like we’re electron microscopes or stethoscopes or infrared film or X-ray plates.

“Everything Is Everything”

I got my title for the story when I heard the hip-hop scripture by Lauryn Hill: her 1998 song “Everything Is Everything.” I’d forgotten about it, though it’s on an album I own The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill. I heard the in an Urban Outfitter store in Berkeley, and at the time I was kind of mentally dismissing it, as the line seemed kind of obvious, and wasn’t initially realizing how heavy it is. And then I realized this could be a good title for my story as, in the Absolute Continuum, everything really is everything. “After winter must come sprint,” says Lauren.

“Everything Is Everything” has a very cool video —you need to watch it at least twice, and I’ve actually watched it four or five times now, and will watch it more times. It shows a giant old turntable-type tone-arm dragging a needle along the streets of NYC, playing the track of the street. The record is rotating around the Empire State Building.

I dreamed that my weird physics friend Nick Herbert was giving me a new psychedelic drug, bit the tab or pill was mixed in with a batch of about twenty other pills, dumped on the sofa cushion next to me, and I was too thirsty to get them down, some of the pills nearly the size of pool-cue-chalk blocks, and pale blue. Like a daily dose of AIDS meds. Then inside the dream I saw, in a small pop-up screen in the corner of a news-show, I saw a sidebar type item on the drug I was supposed to be getting, it was called “Buddha Slime,” and it was a slick gel presented beneath a layer of transparent plastic, like on those old mood ring thingies. I woke up, drank a lot of water, laid down to go back to sleep and earnestly hoped I could return to the same dream and get my Buddha Slime, but didn’t get there.

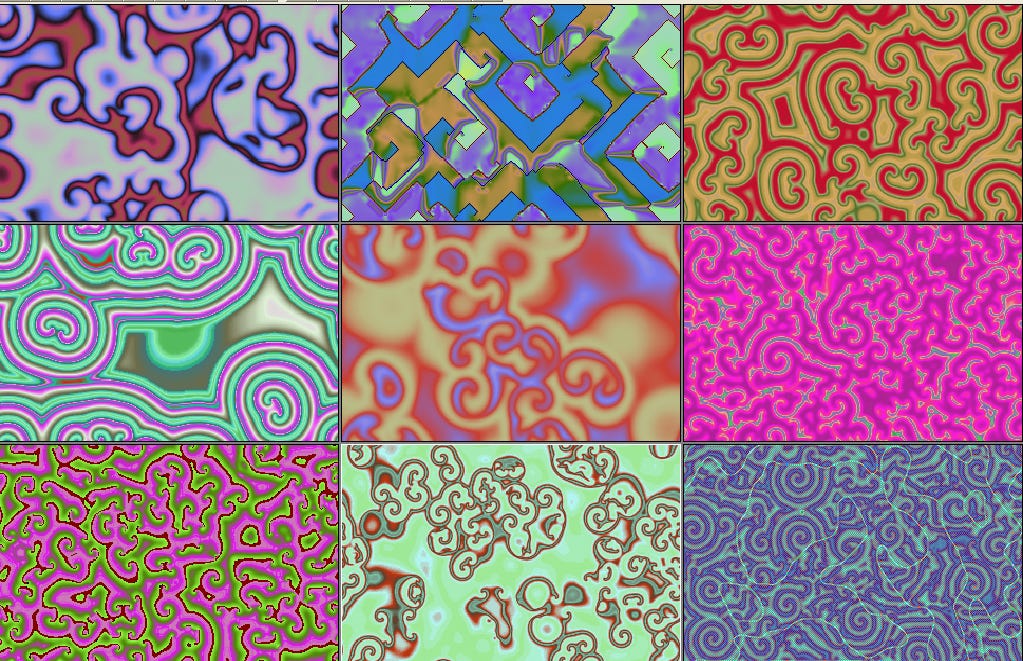

The Smeel Egg

The Absolute Continuum as the end result that I want to get to. I can reason backwards to find out the nature of our man’s dream work. Wick and Vi meet a pair of entitled pricks in a Mercedes which is actually a UFO from the Absolute Continuum. They resemble a man and a woman with smooth skin instead of faces. The entitled prick woman unlocks her trunk, and Wick takes out an egg. It has a leathery shell like a turtle egg, or maybe a jellied covering like a frog egg.. Maybe the shell has galaxies in it? And it hatches after they get it home and set it on a nest in the chicken pen. Some stuff oozes out. I call it smeel. It looks like whiskey in water and breathing it gets you high. Ta da! Glorp.

The Absolute Continuum oozes out, yes. Upshot? Vi and Wick nullify some potential threat from the Absolute Continuum? And they normalize our relations to the One/Many civilizations of the transfinite cosmos?

“Five Eggs” acrylic on canvas, August, 2019, 24” x 30”. More info on my Paintings page.

I did a painting with five eggs in it. They are, I might now recklessly claim, an objective correlative for the object in my story. I could have my egg have a branching fractal Russian Doll sequence of smaller eggs in it. But that’s corny. Plain eggs. They contain, respectively an elephant, a snake, a gnome, sick yolky ylem, and a metaquark. Or, for the last two, how about an anthill, and a congeries of math symbols. Or a squawky bird instead of the symbols. I want a swirly Absolute Continuum. I can hardly wait to imagine and describe our world after the smeel comes out and gets Wick and Vi high. Also anxious that I won’t be able to do it.

Sylvia and I went to see Paul Simon at the huge 1920s Fox Theater in Oakland. Wonderful concert, very inspiring. “Angels in the architecture” Paul says in one song. The bright, highly saturated colored stage lights pointing at us some of the time, blinking on and off.

The entitled prick aliens, and the dream, and smeel egg are just a means to the end , which is to be flooding our reality with the Absolute Continuum—although the Absolute Continuum was, always already here. Because Everything is Everything. So, um, if the transfinite/infinitesimal visons were always here, why didn’t we notice? Well, maybe they’re always here, but it’s hard for the average person to notice . Until we get those good old whiskey-in-water smeel swirls from the leathery egg.

Our normal waking state is a type of dream, as G. I. Gurdjieff would say. And if it’s only if we really wake up that we can perceive the AC. The scene of smeel wakes us. And the alien denizens of the Absolute Continuum, and they’re fully awake, they can handle the blaze of info and noise and transifnitude. We’re, like, on the nod most of the time, and then we go even deeper on the nod and sleep and have states that even we realize are dreams. But, even our waking states are dreams as well. But a nice big whiff of smeel wakes us up.

On the drive back from the beach after the entitled pricks give them a smeel egg, Wick can be like I was on Memorial Day, 1970, when I’d taken acid on the Livingston campus of Rutgers, and Sylvia was driving us a mile or two back to our apartment at 43 Adelaide Avenue in Highland Park, with ten-month-old daughter Georgia in my lap…and I thought I was the one driving. And I was telling this to Sylvia. So Wick will think he’s driving the car back to Los Gatos, even though Vi is driving.

Passage that makes me laugh, even though I’m not going to use it:

Vi and Wick scrambled into their car, with Vi at the wheel. She got the engine roaring, and squealed the tires on the way out. Wick was cradling his giant alien egg in his lap. He unzipped his fly to have sex with the alien egg. “Don’t, Wick,” said Vi.

Pushing it and pushing it, like a car stuck in the snow, not letting up, rocking it, pushing some more. And throwing in some weird crazy shit that seems like fun. Here’s an email note to my mad mathematician friend Nathaniel Hellerstein about where the story is right now.

I’m working on a story where this guy keeps dreaming of being at a math seminar on the top floor of the math building at Berkeley. The speaker is a large sea anemone with a head at the end of each tentacle. And they guy can never quite understand the talk, but finally he naps long enough to get it, after twenty tires. And then a man and woman with no faces (just smooth lumpy skin) show up and give him a gelatinous egg, said to be a bud off the anemone. He puts it into his chicken coop at home to hatch. Goes to sleep. When he awakes it’s the next morning, and two of the chickens have become real estate agents and are knocking at his door. Also…his space has become Absolutely Continuous. Waiting now to see what happens next.

The Chickens

Maybe the aliens are realtors. And they take on the form of extra chickens in Wick and Vi’s coop. I love the idea of chickens as realtors. Alien realtors is a move I’m lifting from a 1964 P. K. Dick tale called “The War With The Fnools.” Wanting to check PKD’s wording, which I could almost remember, I found the story on a Russian pirate site called “sickmyduck.”

“Good morning, sir,” the Fnool piped. “Care to look at some choice lots, all with unobstructed views? Can be subdivided into —”

“As long as you’re here,” the first of the remaining Fnools said to Lightfoot, “why don’t you put a small deposit down on some valuable unimproved land we’ve got a listing for? I’ll be glad to run you out to have a look at it. Water and electricity available at a slight additional cost.”

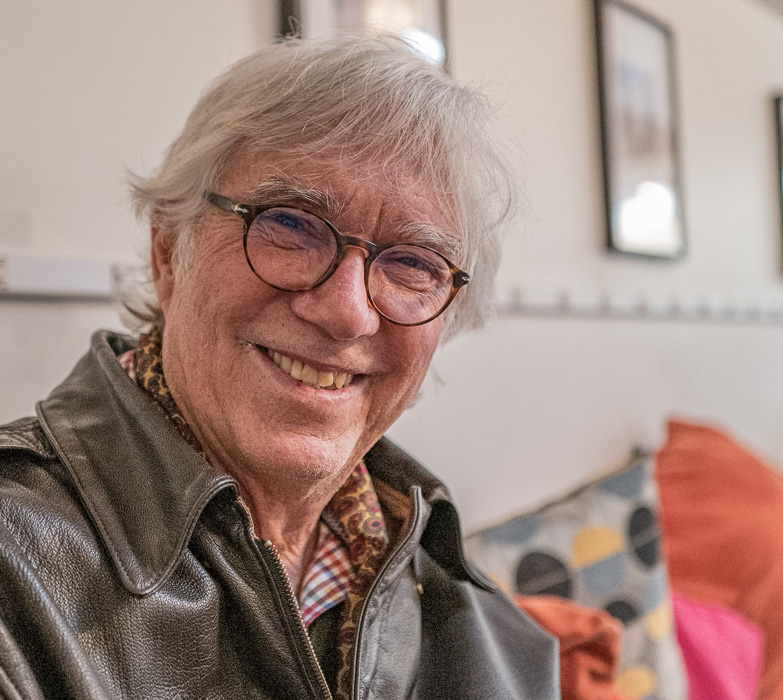

Here’s my photographer/cinematographer friend Eddie Marritz that we saw in SF over Xmas. He took the picture of me that’s higher up on the page, passing my new Leica Q2 back and forth.

And that’s it for Everything Is Everything for today. I’m working on a much improved new new draft that I might be posting soon, also more of my notes for it.

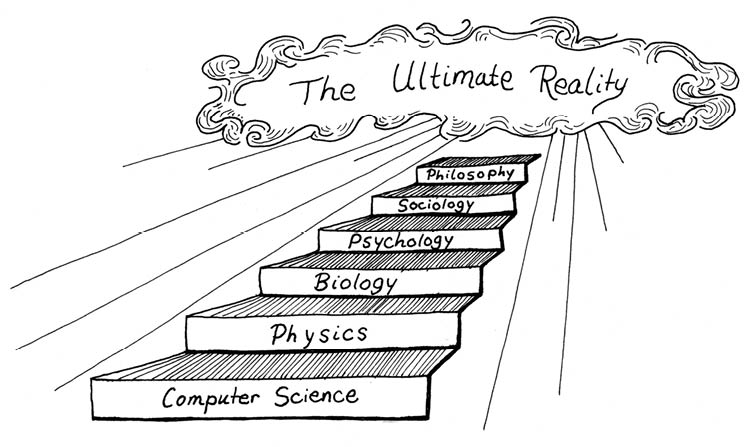

Drawing by Isabel Rucker.

Drawing by Isabel Rucker.