And now came bad news from Louisville. My big brother Embry was suddenly dying of cancer. It came on very quickly. I flew back to Louisville, with my son Rudy Jr. along, and we had a chance to say our goodbyes to Embry. He was very weak. It was good to be together. I held his hand for a long time, and he told me his whole life was flashing before his eyes, bouncing around, and he liked that.

Embry’s son Embry III took this photo of me sitting by Embry Jr on his deathbed. He’s near the end. And I look so…pensive.

As I keep saying, where does the time time go. How can this be happening. So strange and sad to reach this milestone. I always knew it’s coming, but the reality isn’t like I imagined at all. Not even after seeing Sylvia die.

Embry and I were little boys together, seventy-five years ago — and I was thinking of us as little boys in the woods, with something scary drawing near.

Photo above of Stephen Davenport, Embry Rucker III, Rudy Jr, and Peter Graves. Stephen and Peter were two of Embry’s best friends in high-school. Lots of stories. The three of them had motorcycles and used to ride around together, not as hoodlums, but more just goofing around in the countryside.

Embry and Stephen took a famous spring-break trip to Florida, years ago, and they were broke, and hungry, and they went into a restaurant to order perhaps a single egg each. The family at the laden table next to them left the room. Instantly Stephen was on his feet, hunched over their table, and gobbling food. Then they returned. They’d simply stepped out on the deck to look at the view.

Rich, remembered laughter.

The day after I got back to California, Embry actually died, and I flew back to Louisville, this time with daughters Georgia and Isabel along. It was a big funeral, with many familiar faces from the old, old times. I got it together to deliver a eulogy…went though a lot of rewrites, making it be about him and not about me. Read it online at

Embry’s Eulogy.

It’s also worth mentioning that I published two memoirs by Embry under my Transreal Books imprint. You can buy them, or read them online at Embry’s Books.

Faces from the primeval past at the funeral. Shown above is Churchill Davenport (Stephen’s younger brother (their father was the rector of our church (where our father Embry Rucker Sr. became a deacon when he was 40))).

So much to unpack in family stories. Like a fractal, going deeper and deeper, with everything intertwingled. That’s why I called my autobiography Nested Scrolls! To write an auotbio, you have to know how to skim along, riding the sharp memories and the high-points. Like ice-skating.

Popping back up the memory stack: Churchill Davenport. He has truly a hero of my youth. He was very smart, athletic, talkative, persuasive, and with an artistic temperament, going off into side-alleys that nobody else would have thought of. A wild partier and a ladies man. And he did very badly in school. My opposite in nearly every respect. As I say, I greatly admired him. And talking to the 2025 version of Churchill was in no way a disappointment. It was like a reward for having done the eulogy. Seeing how our lives had unfurled.

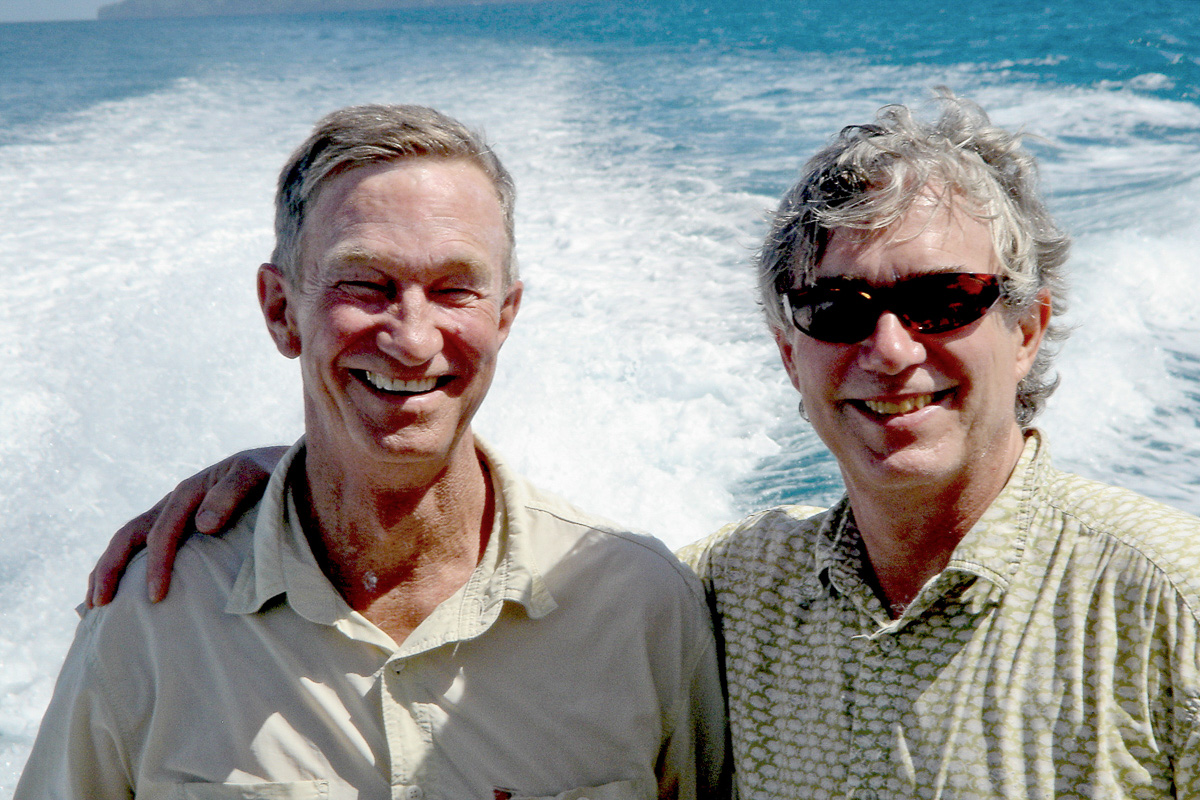

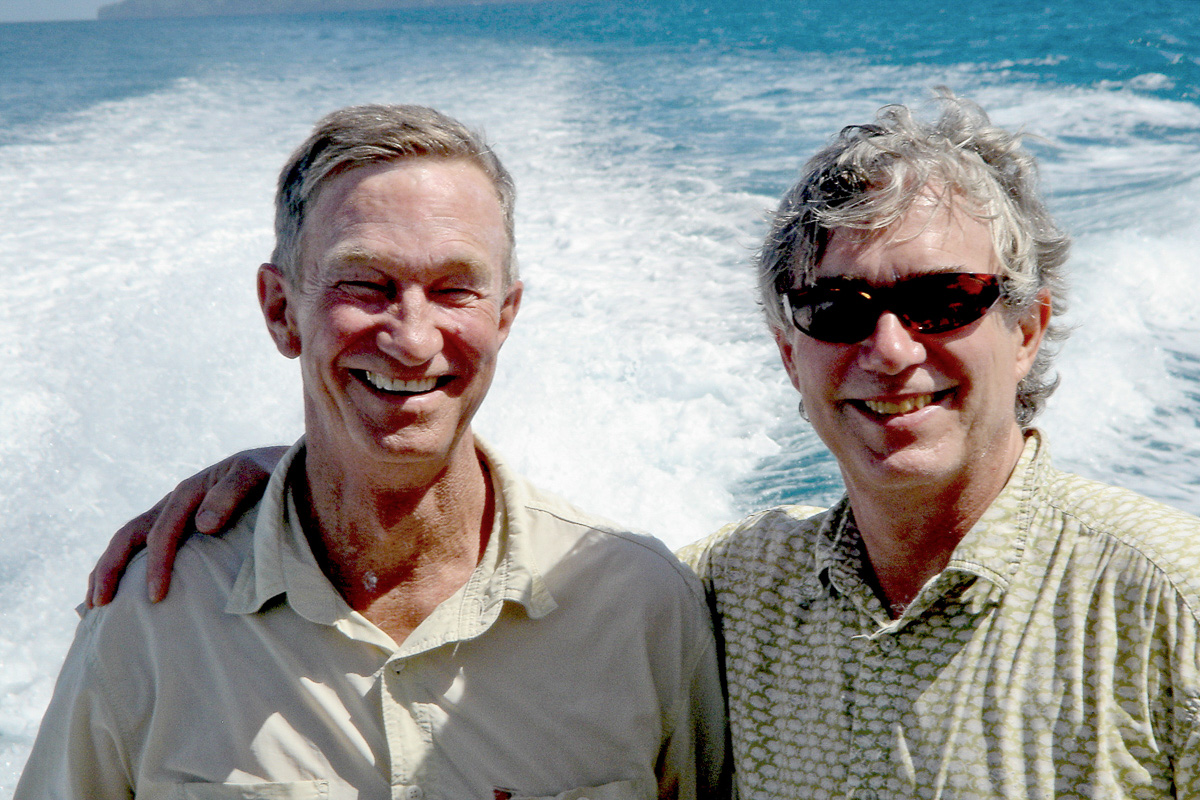

My favorite memory of Embry is the time in 2005 when he and I went on a serval-weeks-long scuba diving trip in Palau, Yap, and Pohnpei in Micronesia, in the South Pacific, inventing the itinerary as we went along. Plus Jellyfish Lake! This shot is on a Sam’s dive boat from Palau, heading for the Blue Corner dive site, which I in fact mentioned in the eulogy. One of the greatest days of my life. Good old Embry.

And again back to lovely Los Gatos. At certain times and angles it feels like a mountain town. In the old days San Franciscans viewed it as a country resort. Love that clapboard in the photo, and that red, and the mountain—called El Sombroso because it’s shady.

I started this painting before I heard Embry was sick. Two of my go-to motifs are tentacles and flying sacers. I started this one with a giant tentacled creature from the sea. And then I heard about Embry being sick. And after he died I didn’t know what to do with myself.

Eventually I picked up this half-done painting and finished it. I tend to work from my subconscious when I’m painting, and not know exactly what the details mean. When the monster with the big teeth emerged, it made sense for me to paint that. But you might well say that the gravestone-shaped thing is Death.

I was reaching a point in the writing of Sqinks where I wanted a whole bunch of these blobby little sqinks to merge together into a super sqink. And seeing this fine yam, or sweet potato in the supermarket, I realized that’s what my super sqink should be like. A giant yam.

Years ago in Lynchburg, Virginia, I spotted a cardboard box for shipping a brand called “Playboy Yams.” And I wrote a ditty.

I’m eyeless and I’m waxed,

I’m orange all the way through,

I’ll be your playboy yammy

Now, what are you gonna do?

I’ll be your yam

I’ll do what yam boys do

I’ll be your yam all night

And in the morning too.

This is a spot on St. Joseph’s Hill near where I live. Sometimes I’ll bring a printed manuscript here and sit on a step, reading and correcting it. I’m lucky to have this view, I’ve been walking up here since 1986. Nearly forty years. About half my life. Nearly every day I ask myself: Where did all that time go? How did I get here? How can I be so old?

And here came Christmas again. The second without Sylvia. Even with her gone, I’m still putting up Christmas trees, at least so far. I do it for myself, really. It would be too sad not to get my little holiday treat. So I schlep out and bring in a tree on top of my car, as always, and dig out the ornament box from the basement.

Hanging the ornaments together used to be a thing. Last year the grandkids were around to help me hang them, but this year I hung them alone, and I wasn’t sure how it would feel. But it was fine, it even felt good. An annual ritual, honoring what’s come before, what’s to come, and where we are right now, putting our beloved baubles on our tree.

Rudy and Georgia, eccentrics in San Francisco!

Isabel and Georgia on Christmas Day.

The photo shows a crazed round of this multi-deck Hungarian card game that the family plays at holidays. Each player has a deck of cards, and the goal is is successfully play all your cards—with everyone playing on the same heaps at once—and when your cards are gone you scream “Stock Out” as loud as you can. And that’s the name of the game. Love how the wide-angle setting on the phone camera makes Jasper’s arm so frighteningly long.

Around now I scraped together my money and upgraded from my Leica Q2 to a new Leica Q3 43. It hurt to spend so much. But I had to have it. First picture of me.

And this is the first photo of Barb!

A traditional photo I like to shoot. The stuff on my desk near the computer, or to the side of it, or behind it. My desk is quite large, it’s a so-called Geek Desk with basically a table on top, and engines and levers underneath, and you push a button to move it higher or lower, so you can switch between sitting and standing as you endlessly work that keyboard, like a tattered person in rags working the Reno slots. Pull me a winnah! I won’t annotate the full panoply displayed, but the painted-upon sphere is a kind of sketch or model, by my genius artist friend Dick Termes. His finished works are big painted spheres more like a meter across.

Playing with the new camera, looking for things to shoot. Here we have a would-be Klein bottle, a skug, and George. The skug is a model 3D-printed by a loyal fan, representing a type of critter in my novel Turing & Burroughs. George was knit by my grandmother Lily von Klenck; I think she got the plastic head in a yarn shop. Our kids always liked George. Nice move on Grandma’s part to knit George so his arms point two different ways.

Always fun to photograph reflections.

And here I am, the empty man, with steady hand, the man of shade.

I see this oak tree every day, and every day I love it. All hail the gnarl!