A couple of posts ago, I was writing about “Virtualization.” And my attention was called to “True Names,” a 2008 novella by Benjamin Rosenbaum and Cory Doctorow, about competing layers of VR. You can find “True Names” either online or in print in Lou Anders’ Fast Forward 2 anthology—I don’t like reading long thing on the computer screen, so I actually got a used copy of Fast Forward 2 for about $3. And I read “True Names” this week. And it sets off all kinds of thoughts, as did a comment that Benjamin Rosenbaum made on my initial post.

Spoiler alert—I want to discuss the idea behind the novelette in some detail here, and what I say will give away some of the tale’s surprises. (On the other hand, if you do read this post before the story, you’ll understand the story better.)

The set-up in “True Names” is that we have three competing reality systems: Beebe, Demiurge, and Brobdignag.

(1) Beebe is a videogame-style VR world, where competing agents live inside a computationally generated reality that uses repurposed ordinary matter as its underlying computational engine. To give it a computer sheen, Doctorow and Rosenbaum cast the characters into the form of Unix-style entities called “strategies” and “filters,” and when they split in two they’re said to “fork” (Unix-style). But most of the time the chracters take on a colorful appearance.

(2) The nature of Demiurge was a bit hazier to me—my sense of it was the Demiurge was devoted to preserving, park-like, as much of ordinary reality as possible, although I wasn’t quite clear what computational substrate the Demiurge creature(s) run(s) on. One might suppose that the Demiurge is, as the name suggests, the universal consciousness that exists Hylozoic-style within ordinary reality. The “divinity” that underlies the natural world.

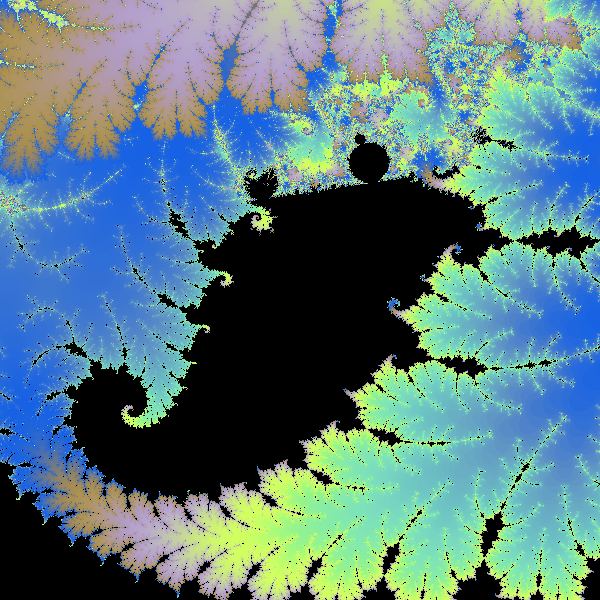

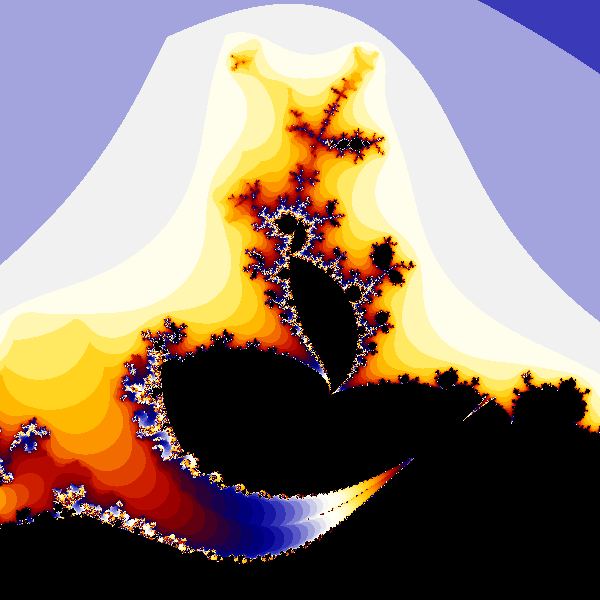

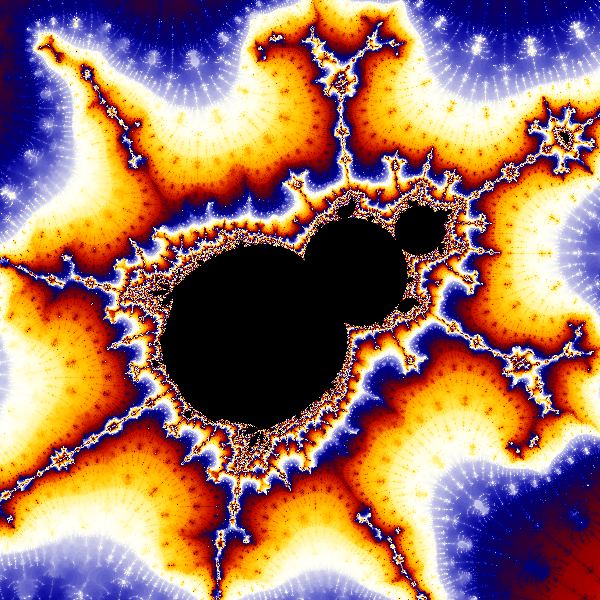

(3) Brobdignag is an omnivorous gray-goo kind of reality that’s eating up all matter and space, converting it into a uniform, distributed computation that I would think of as being a cellular automaton—or CA. A CA, by the way, is a computation arrived at by dividing space up into tiny “cells” and having each cell run exactly the same computation, over and over, in parallel. As computer scientists learned in the 1980s and 1990s, (see the images on my CAPOW page) you can in fact get lovely, emergent patterns in a CA, so the restriction to “simple repeated programs in cells” is in fact no more limiting than are the laws of physics which are, after all, “simple repeated rules at points of space.” Brobdignag is an off-stage menace till the very end of the tale.

The kicker in the story is that the Beebe and Demiurge characters keep discovering that their Beebe or Demiurge “realities” are in fact simulations being run by an opposing camp.

It’s not always easy to discover whether your “reality” is a simulation, and initially the characters believe that, “No inhabitant of an emulation could ever discern the unreality of their simulated universe.” But then the character Paquette finds a rather simple mathematical proof for the so-called Solipsist’s Lemma.

“An emulated being can detect its existence in emulation, and there is a way to find the signature of the emulator in the fabric of the emulation. Specifically, in certain chaotic transformations, a particular set of statistical anomalies indicates the hand of Beebe—another, that of Demiurge.”

But… “The numbers seemed to imply that we were in emulation . . . but not in Beebe, nor in Demiurge. In something else, with characteristics that were exceedingly odd.”

[I haven’t done jack in terms of photography lately, so I’ll be using some images and a video of fnoor-like fractals, for an explanation of them, see my post , ”Cubic Mandelbrots and the Rudy Sets”]

And at the story’s end, the competing Beebe and Demiurge characters learn that the great competition is long over, they’ve been simulations living in Brobdignag all along.

Hegelian that I am, I sense a dialectic triad here. Demiurge, or plain old godly Nature, is the thesis. The antithesis is Beebe, the by-now-ubiquitous-in-SF artificial VR that I railed against in my post, “Fundamental Limits to Virtual Reality” and its follow-up post, “Limits to VR #2: Answers to Comments.” So then, if “True Names” is indeed in dialectic form, the synthesis should be Brobdignag.

How so? We can regard Brobdignag as being the two opposing things at the same time: “natural reality” and “computed reality.” And to some extent this seems to be what Doctorow and Rosenbaum have in mind in their closing pages where we hear a voice from Brobdignag.

“Those little engines—void-eating, gravity-spinning, durable, expanding through the territory of known space—those aren’t us. They’re just what we’re made of. That’s right: we arise in all that complex flocking logic. … We are lucky: we have the gifts of abundance, invulnerability, and effortless cooperation. Let us enjoy them. Let us revel. Let us partake. Let’s get this party started.”

It’s a nice twist although, philosophically speaking, I don’t really see a need for Brobdignag. As I’m always saying, the natural world already is incalculably rich. But my personal opinions are kind of irrelevant here, as we’re talking about an SF story, and about the moves that the authors took to make it work. “True Names” is a good story.

I’m especially intrigued by the Solipsist’s Lemma. When I was working with the Cyberspace project at Autodesk in the 1990s, I used to talk about this notion with John Walker. We were noticing that certain kinds of computational round-off errors would, in time, degrade a virtual physics simulation. Planets, for instance, would move out of their proper orbits. And Walker was saying that maybe there were some weird things in particle physics that indicated that our reality was in fact a slightly shoddy simulation.

I used a variation of Walker’s notion in my transreal, VR, artificial life novel that emerged from my time at Autodesk, The Hacker and the Ants. In my novel, I had the idea of making these simulation errors take on the form of odd-looking inconsistent computer graphical objects that I dubbed fnoor.

Somehow “fnoor” seemed like just the kind of word that my new code-hacker friends like Bill Gosper would come up with. And, God knows, I was seeing plenty of fnoor coming out my initially ineffective attempts to program such simple shapes as dodecahedra. So in The Hacker and the Ants, there’s cracks where some of the “walls” of the VR join up, and inside the cracks are bits of…fnoor. A race of voracious artificially-alive VR ants are hiding inside the fnoor.

The cyberspace crack I found myself in held an odd, drifting piece of geometry, an “impossible” self-reversing figure of the type that graphics hackers call fnoor.

The piece of fnoor was of wildly ambiguous size. Relative to my tiny dimensions, the fnoor first seemed to be the size of my car, but a moment later it loomed as large as the pyramidal Transamerica building… The fnoor was a clump of one-sided plane faces that seemed haphazardly to pop in and out of existence as the clump rotated. The fnoor’s vertices and edges were indexed in such a way that the faces failed to join up in a coherent way. There was no consistent distinction between inside and outside, leading to a complete failure of the conventional cyberspace illusion that you are looking at a perspective view of an object in three-dimensional space.

The rotating fnoor changed size irregularly; at a moment when it looked much bigger than me, I sprang forward and landed on it. I ran across the faces, which flipped out under me. I still had seen no ants. Finally I came to a crazy funhouse-door in the fnoor in the dense angles of the fnoor; I squeezed through it and the fnoor turned into a solid model that lay all around me.

Just recently, before reading “True Names,” I was thinking about revisiting this notion, in fact I’d made an outline for a short story called “Fnoor.” And now “True Names” energizes me, I like how the explicitly worked out the “Solipsist’s Lemma.” Hopefully I’ll get around to writing a longer form of my own story in the next month or two, but for now, here it is in outline form.

“Fnoor”

Point of View: a more or less normal woman who has a crazy mathematician friend.Setup: The mathenaut zooms in and finds an scary apparition in a high-degree computer graphic, it’s some new kind of fractal that he’s investigating as a kind of retro move. He calls these weird little shapes fnoor.

Twist: He finds the same kind of fnoor in a scanning-tunneling-microscope image.

Flash: He concludes the natural world is generated by an algorithm.

Task: What does the world’s computation run on? His woman friend, the narrator, says that consciousness is the substrate. The mind is the “metal” of the “machine. The mathenaut is okay with this idea, but then he begins wondering what the underlying the consciousness is running on. Are we in a strange loop or in a tower of virtual machines.

Action: So our hero seeks out fnoor in our consciousness—perhaps he starts with the phosphenes you see when you press your closed eyes. And now the mathenaut begins changing the world by changing the operating system of his mind. And thanks to entanglement, everyone else’s world changes too. It’s for real, at one point the mathenaut conjures up a ragged hole in space, a hole the size of a knapsack, and he pushes his hand into it.

Finale: By now his woman friend has left the mathenaut, and he’s trying to get her back. She takes action to stamp out the fnoor. And…[wait for the zinger.]

April 19th, 2010 at 8:38 pm

The Solipsist’s Lemma is pretty interesting, but I don’t buy it. I contend, as I’ve said before, that any attempt to get down to the computational fabric leads to aliasing. What you see looks consistent within the fabric because the fabic is closed.

April 19th, 2010 at 11:52 pm

I was thinking of something similar. Each layer of virtualization is slower than the last, but due to the fact that the VM layer’s clock is being pumped externally, it has no ability to determine how fast it’s actually moving relative to the external reality. Therefore, you could be an arbitrarily complex simulation that takes an arbitrarily long period of time to evaluate, but you would still perceive the passage of time as fleeting.

In fact, to torture the VM model even further, the universe could just as easily “amb” (a LISP method that lets you run big chunks of code until it either returns a value or hits an exception. You can set it up so that if it hits an error or returns false, that whole execution chain magically goes “Poof!”, and it’s like it never happened. Start over from where it was called and try again with the next value), and you would never notice that it had happened, because that entire experiential branch was popped off the stack.

Additionally, there’s something called a side-channel attack that’s quite fun. A practical example is that you can run a video game in one process, and then poke at its memory in another process. The game is “unaware” of the external interference, so if you change its memory, then its entire reality is changed without it even knowing that the change has occurred. Certain brain injuries can cause similar effects.

You can even get more elaborate. Some video games come with additional software to defeat cheating (which represents the intellect in search of evidence that the world is a simulation), but the same side-channel attacks make that anti-cheating software just as vulnerable to world-view tampering (usually from a different core of their multi-core processor).

April 20th, 2010 at 6:22 am

Emilio and Failrate, you assume, I take it, that the underlying operating system is arbitrarily well written. It’s common in SF stories for postulated technologies to be seamless fulfillment of their user’s desire, but not found in nature. I put it to you that in any actually existing emulation, there is probably a way to write a program which can tell if it is running in emulation or not.

For instance, were I a gifted Amiga programmer, I expect I could write some Amiga code which could tell, in some clever way, if it was running on an actual Amiga, or one of the Amiga emulation packages one can nowadays download. While it’s true that one couldn’t determine whether one was running slower in reference to an external reality, for instance, one could observe how fast different kinds of operations were relative to each other. The author of the emulation software is unlikely to have put much effort into making sure that the relative speed of floating-point and integer calculations, say, exactly replicate the relative speeds which pertained in the original platform — both because the emulation programmer simply wouldn’t think of it, and also because there would be costs to such emulation precision, which would have to be traded off against other goals.

So one question is, are you assuming emulators who are infallibly precise and totally devoted to making the emulation impossible to detect at the expense of other goals? Or are you looking for emulators who are somewhat “like us” — fallible, and with concerns other than fooling us? The Solipsist’s Lemma would be presumably about the second kind of emulation.

(Note that I think the popular extropian idea that we are living in a consciously intended emulation of our own existence to be rather self-obsessed anyway, and also rather infatuated with the technological specifics of our own moment of history. First of all, if we were, improbably, in an emulation of anything, it would be most likely be an “emulation” intended to produce some effect entirely different from emulating us, first of all, and we would be part of the fnoor; secondly, calling it an “emulation” in the image of the operating systems of today would be about as accurate as ancients imagining the stars as torches mounted against a rotating vault of ceiling-sky…)

April 20th, 2010 at 9:22 am

I think there are many ways in which one might notice that one’s reality is a simulation.

There are the round-off artifacts that I mentioned before. It might be that the continuous-valued laws of physics are always failing, and people deduce that it’s because the analog number values keep getting truncated.

There could be extreme jaggies, that is, you’d try and draw a straight line and it would have a stairstep edge to it. To make this a dead giveaway, we’d have, let us say, the smoothness of your vision be finer than the jagginess of the lines.

There could be statistical things such as hinted at by Cory and Ben.

There could be odd little holes in space, the fnoor that we pick up on very close examination.

What if the whole edifice of quantum mechanics is simply a misguided interpretation of the fact that our reality is a simulation with finite precision!

Re. Mind and Reality, I was thinking about the Strange Loop notion yesterday, and it does have some appeal. Our minds are simulating the world we live in, and the world is simulating our minds. The worldsnake bites its tail. The Dream dreams the Dreamer. This is, I think, a not uncommon philosophical position, although it’s not usually couched in terms of computer emulations. In this case, what is the fnoor, and what does it mean? Perhaps a mantra or a mandala is the fnoor…

April 20th, 2010 at 10:53 am

(Here via Ben’s blog.)

I was willing to accept the Solipsist’s Lemma for the sake of a story, but (as I’ve mentioned to Ben) my problem with “True Names” is the supernatural consistency between different levels of emulation. The narrative repeatedly moves from a version of a character running at n levels of emulation to a version running at n-1 levels of emulation with no discontinuity. I don’t see how that could happen. Even with perfect emulation there would be differences in behavior, if only because the characters become aware of the fact that they’re being emulated, and that can’t occur identically at every level unless you have an infinite regress. Moreover, the idea of the Solipsist’s Lemma means that emulation is not perfect.

As for Rudy’s suggestion that quantum mechanics might be a consequence of reality being simulated with finite precision, that would only make sense in Ben’s scenario where our entire universe is the fnoor. QM so thoroughly saturates physics that if it isn’t an intended part of the simulation, then the goal of the simulation is not something we’d recognize as a universe at all; it’d have to be something not built out of atoms at all.

The idea that QM’s oddities are a result of imperfect simulation arises, I think, out of an assumption that our intuitions about the behavior of physical objects are trustworthy, and that if our intuitions don’t match reality, then there’s a problem with reality. But I think there’s a much simpler explanation: our bodies are macroscopic, and our brains evolved to deal with reality at a macroscopic level, where our intuitions work quite well. If we’d evolved in an environment where QM effects were regularly visible, we would have evolved brains that understood QM intuitively. Likewise, if we’d evolved in an environment where relativistic phenomena were regularly visible, we’d have brains that understood relativity intuitively. We shouldn’t rely on our intuition in domains it wasn’t intended to handle.

April 21st, 2010 at 4:27 am

Ted is of course completely right about “True Names”: the oddly perfect synch between versions of the same characters at different levels of emulation — emulations which, although synched periodically based on incoming data, are in some cases at relativistic distances from one another — is the handwaviest part of that story. In fact, that bit rather moves the story into slipstream, rather than (however tenuously) extrapolative science fiction. The only way to salvage it as extrapolative SF (and I’m just being playful here, because of course this isn’t in the text) would be to posit the future discovery of that some different kind of causality obtains in our world from the one that our science supposes — some kind of overdetermining meta-narrative that constrains “what happens” in a nonlocal way, which would allow us to deduce minute details of events happening at vast distances from little and belated data. Something like the archetypical dimension of reality in Hal Duncan’s Vellum, or the Five Causal Forms from another story of mine.

I think Ted is on solid ground with the idea that our macroscopic intuitions lead us astray with reference to QM. I’m not sure it follows that QM being central makes it “an intended part of the simulation”; the effects observed and accounted for by QM are certainly central, but there are, of course, an infinity of theories which could have been constructed to account for them instead of QM. There is an ineluctable gap between reality and descriptions of reality, so our emulators couldn’t very well have us come up with QM just by designing the universe such that QM would be an adequate description of it.

(I guess we could think about two (among perhaps many more) basic kinds of emulation. One would be “generative”, in the sense that it would be created, with certain constants and rules, and then whatever emerged would emerge. The other would be “rigged” in one way or another to produce a certain result — an example of this would be a world created to emulate a particular historical moment, complete with a false history of that moment, or even jerry-rigged and tuned so that a particular “known” historical sequence would be replicated [which, given the universality of fnoor and its likely derailing effects, not to mention the impossibility of knowing more than a vague approximate abstraction of the details of an actual historical sequence, would probably require constant intervention by the emulators]. In a rigged emulation, emulators can intend us to come up with anything they like, and we’ll come up with it; I was talking about a generative emulation in the above paragraph).

If we were in an emulation with suitably regular and predictable fnoor effects, we would observe its fnoor and make up physical theories which included it, and thus we would not be surprised to find that those fnoor effects were totally central to our physics. However, we would be surprised to find that the underlying physics of the emulator’s world (or the world they were trying to emulate) were closer to our prehistoric brain’s intuitions about the world, than the fnoor-inclusive theories! Finding out that everything odd and counterintuitive about QM was a fnoor effect, and the “real” world was pre-Heisenbergian, would be very similar to finding out that the Copernican solar model was fnoor, and the “real” solar system’s topology and dynamics were Ptolemaic. It’s much more likely that the “real” world — whether we’re in an emulation or not — is much, much stranger (to us) than QM.

April 21st, 2010 at 10:19 pm

@Ben

BTW, I really, *really* liked True Names 🙂

>> For instance, were I a gifted Amiga programmer, I expect I could write some Amiga code which could tell, in some clever way, if it was running on an actual Amiga, or one of the Amiga emulation packages one can nowadays download.

I can think of certain cases where you could determine if you were in an emulator or real hardware, but all of the cases I can think of rely on knowledge of the comparison of the properties between existing hardware and the emulators. For example, different generations of the Commodore 64 had slightly different flaws and behaviors, even though they were all equivalent devices. Most emulators attempt to use software to ameliorate those flaws for the sake of compatibility. I have to assume that even good emulators might also introduce new bugs or have slightly different outputs due to precision or what-have-you.

The problem with this particular approach is that you always need something to compare it to. We only experience this reality, therefore we don’t have an alternate universe upon which to base our comparisons.

Perhaps the fnoor is all around us, but due to our inexperience, it just looks like a perfectly reasonable expression of physics.

Also, the emulation needs not be perfect or god-like. Back of the napkin: It just has to be at a resolution and sophistication of at least a magnitude greater than a group of about seven extremely smart, motivated and well-informed humans with a research grant and access to a good deal of finely calibrated scientific equipment. That’s not a lot of computing or analytic power. Now, if we humans could get really organized and learn how to share knowledge properly, we might start picking out the fnoor from the mundie.

April 22nd, 2010 at 10:49 am

I too approve of Ben’s notion of the universe being fnoor. If this were true, and proven, then it would give us a vested interest in the buggyness of the ultimate program. We’d be in danger of being debugged, but I think that ultimately the glitches have the upper hand.

April 22nd, 2010 at 10:56 am

By which I mean, “we” glitches.

Also; fnoor is easy to find. Any optical illusion is neural fnoor; they’re glitches in your brain’s visual wiring. Delusions are psychological fnoor. Ideology is social fnoor. They only exist because of bad programming.

April 22nd, 2010 at 1:36 pm

“Fnoor” sounds like “fnord”, which is an in-joke from Robert Anton Wilson. In his Illuminati series, everyone was conditioned during childhood to fear and forget the word ‘fnord’. The Illuminati then exploited this mass hypnosis by scattering the word ‘fnord’ all through the mass media, especially in dangerously truthful stories, but in none of the ads. When Robert Anton Wilson characters get Illuminated, they can see the fnords.

April 22nd, 2010 at 7:38 pm

Will Wright and Brian ENO on Generative Systems…. (at the Long Now Foundation)….

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UqzVSvqXJYg&feature=channel (Fora Tv)

April 23rd, 2010 at 3:32 am

I feel like my mommy finally plopped me down in the right sandbox. Or something like that.

I landed here via reminisces about M2k. I’ll digest some more before I post anything substantive.

Halloo!

April 30th, 2010 at 3:54 pm

Ted, I’m familiar with the argument that QM seems unnatural because we are large-sized beings. Nevertheless, I find it interesting, as an SF writer, to think about ways in which QM could in fact be wrong, and the world could be more deterministic and classical than we realized.

I have a discussion of this in my book THE LIFEBOX, THE SEASHELL, AND THE SOUL, here’s a link to a relevant passage in a part of the book that is online.

http://www.rudyrucker.com/lifebox/lifeboxsample.pdf#page=120

“My opinion is that there are in fact underlying psychological

reasons driving the conventional insistence that we should welcome

quantum mechanics and the destruction of determinism. Often when I hear a

popular lecture on quantum mechanics, I detect a lilting, mystery-mongering

tone. ‘Be happy! The universe is incomprehensible! How wonderful!’

The rejection of determinism seems to provide some people with a sense

of liberation.”

May 2nd, 2010 at 1:04 am

Just to be clear, I’m not saying that we should welcome QM; I don’t like it myself. I’m a fan of determinism. I just don’t think we should trust our intuitive ideas of what makes sense, if they’re in conflict with experimental evidence.

May 11th, 2010 at 1:25 am

Rudy -& all you altiversal avatar, herein-

… might i suggest that the Mind itself is the Fnoor — at least, our conscious, discriminatory intellect that leads from the left-brain, and collapses the state-vector into it’s continuity and particularizing of palimpsestic potentia – manifesting as ongoing events, the mental “Maat” as world-line [or “string”?] … one might also say that the Mind is, too, an “Improbability-Drive/r” [a-la Douglas Adams’ Hitchhikers’Guide SF], perhaps more-so on the right-brain side of the ‘particle-/-wave duality’-analogue of our experience; whence Imaginary Waves of Multiversal M-branes curl through the coincident synchronoos — both True AND False, like unproven intuitions yet foreshadowing [as per “The Laws Of Form” meta-calculus of G.Spencer-Brown] . . . . — anywise, the open/ closed & bounded/ unbounded matrix- permutations of a UniVerse’s “OnTopOlogy” might always have a Godel-ian incompleteness to them, if not truly monads in an Ulterior CosmoLogos, hmmmm?

… whups, sorry to ramble into prosody … – so much to say, such a narrow apeture to squeeze points through …

more – Soon & @t Random –

Uncle Sumer {aka ETC}

May 11th, 2010 at 1:44 am

BTW, i was glad somebody mentioned the “fnord” … i presume the “fnoor” was so-called in order to evoke R.A.Wilson’s memes, hmmm?

— also, – i’d like to say — i’m quite glad to have found your web-prescence, here, Muse Rudy, (thanks to the Metafilter site, which has a number of comments on your QM&SF post).

Uncle Sumer {{btw, – if you two are conversant much, i might mention that i suppose it just possible that prof. Michio Kaku might recall me as “Vex Vuthor”, years ago posting to a yahoo-group devoted to his string-theoretics, -where i did some debate & zen- “WuLi” lecturing, and the one illustrated poem he may’ve liked …}}