I won’t be blogging over the next week. Here, to tide us over, are fifteen Christmas-related memories from my memoir, Nested Scrolls.

1. When I was a boy in Louisville, on Christmas Eve, we’d go to church and there’d be a Christmas pageant.

One year I was Joseph, and I had to spend twenty minutes in a robe staring into the Holy Cradle, which was a cardboard box with a light bulb in it. I passed the time by mentally estimating the volume of the Hi-C cans that had once filled the box, and comparing this volume to my estimated volume of the box.

The best part of the pageant was when three of the men at church would play the Three Kings and walk up the aisle singing verses of “We Three Kings.” At first I wouldn’t be able recognize them in their robes and makeup, and then I’d realize I knew them, and it was exciting to see them transformed.

Afterwards we’d go outside and the sky would be black with twinkling stars, the air thin and cold, and Christmas almost here.

On Christmas mornings, Mom would arrange a fan of books around the base of the tree for Embry and me. Some of the books were science fiction. Embry plowed through any and all the books—he was an omnivorous, inexhaustible reader. But it was I who cherished and pondered the SF.

2. One Christmas, my friend Niles and I both got large Erector Set kits, red metal boxes filled with struts, little nuts and bolts, wheels, and a real engine that you could plug into the wall. The kits came with instruction pamphlets filled with detailed drawings of things you might construct. After some preliminary projects, both of us set to work on the largest item in the book: a Parachute Ride, which was something like a merry-go-round, but with dangling seats.

We had endless consultations over the details—which weren’t all that clear in the pictures. Eventually I managed to build a Parachute Ride just like the one in the picture, but Niles wasn’t quite so patient as me, nor so inclined to follow detailed instructions, and his looked a little—different, not that it didn’t work just as well. I was intrigued by the evidence that you could in fact ignore instructions and still get something to work.

3. I spent a year at a boarding school in the Black Forest of Germany when I was thirteen. The school was run by some Quaker-like religious sect. For some reason, the biggest holiday of thier year seemed to be the First of Advent. This was the one day of the year when good food was served in our dorm. And in preparation for the First of Advent, each of the boarders had to make a little work of art to be displayed in the common rooms. The most popular projects to make were stellated polyhedra—I myself made a humble four-sided tetrahedral pyramid with a narrow pyramidal star-point glued onto each face, but the older boys made exceedingly intricate models, networks of a hundred or more squares, triangles, pentagons and so on, with a specially folded slender point growing out from each of the polygons.

My mother came over for a visit at Christmas, bringing me a number of the plastic airplane model-kits I liked, also an algebra textbook. I’d been concerned that I was missing out on my first year of algebra—back home, they started algebra in the eighth grade, and I’d been looking forward to it for several years, even though I didn’t exactly know what algebra was.

4. In the ninth grade, I attended such a small private school that they put me on the varsity football team. We played a full season against teams fielded by other private schools, and we lost every one of our games. I especially liked the away games, where we’d drive in a caravan of cars, sometimes quite a distance, down rainy two-lane Kentucky and Indiana roads, with stops at roadside restaurants for wonderful greasy dinners, and lots of manly joking and story-telling at our table.

Right before Christmas vacation, we had a sports banquet, and we all got letter sweaters. Coach Kleier made a speech in which he said there was one person here who exemplified his idea of courage: Rudy Rucker! Pop was proud and thrilled, he talked about this event for years. He said I was so small that when I stood up from my chair to get my letter, my height barely changed.

5. When I was home for Christmas vacation with my parents in the senior year of college, my brother was finally back from the army, and looking to stir up some trouble.

“I guess you’ll be needing one of these pretty soon, huh, Rudy?” said Embry, pointing at a full-page ad for diamond rings. Naturally he said this in front of my mother.

Mom started vibrating with joy and approval. She and Pop were crazy about Sylvia. The next thing I knew, I’d gone to the bank to withdraw my leftover construction-work money, and had driven with Mom to Galt Jewelers in DC to pick out an engagement ring. And while I was at it, I wrote Sylvia’s father, asking for permission to marry her. Sylvia told him to say yes. He appreciated this old-school approach, and made a point of getting the best possible stationery available to write me back.

6. Our parents were thrilled to have a granddaughter, and we all visited each other a zillion times, even flying Georgia over to Geneva for her first Christmas. Sylvia and I went out to play in the snow while her parents watched the baby.

“But you are still children, too!” exclaimed her father when we came in from the snow. “How can you have children?” I was twenty-three.

7. In Virginia, at age sixty, my father had a heart attack. In order to replace his clogged coronary arteries, his surgeon turned to bypass surgery.

This operation was still quite new. They opened up his whole chest, leaving a vertical scar at least a foot long. The drugs and the trauma had a bad effect on Pop. He became disoriented—once on the phone he was telling me that he could see American troops burning Vietnamese huts from his hospital room window, although, near the end of this conversation he said knew it was a hallucination. I can only imagine how freaky and unpleasant his dreams must have been.

He had to go back to the hospital a couple more times until his condition stabilized. I remember once, at Christmas time, we were visiting my parents with the three kids, and I snuck newborn Isabel into the hospital under my coat to cheer Pop up. Coming upon Pop happily cradling the baby, the night nurse smiled and said, “Congratulations.”

8. Mom, Pop and Sylvia’s parents were all at our house in 1977 for what was to be our last Christmas in Geneseo, New York.

It was a classic holiday—Georgia got a Barbie Townhouse that she’d been longing for, Rudy got a Lionel electric train on a loop of track, and Isabel had a nice red fire-engine that she could pedal. Sylvia’s father got us a new TV, and when I shorted it out by spilling a scotch and soda in through the vent on top, I took it back to the giant discount store it had come from, and they gave me a new one. Sylvia was in a sewing group with the manager’s wife, which helped.

We took the grandparents out to go sledding with the kiddies one afternoon, but that wasn’t a big success, as the temperature was fifteen below zero. The breeze coming up from the valley felt like the air from a freezer, like the fumes from dry ice.

In spite of the tensions, Christmas was cozy. I loved the pleasant physicality of lying on the rug like a dogfather in his den, with the kids crawling on me, poking and wrestling. Sylvia was great at assembling presents for us all, wrapping them up like works of art, writing cute labels, arranging them under the tree. By now a number of ornaments had migrated from our parents’ houses to ours. Little Rudy and I squeezed under the tree, staring up at the wooden figurines and the colored lights. Mom was endlessly considerate with the children. She’d relax in their presence, forgetting her worries, reading books to them, handing them toys, smiling and nodding.

9. My Lynchburg neighbor, R. G., liked mowing his lawn and trimming his hedges, but he didn’t have a hedge-trimmer. One day he convinced me to help him tidy up the top of his hedges by helping to hold his lawnmower up in the air and lower it onto the sprouts. We each holding two wheels, standing on either side of the hedge. After a couple of minutes, it became evident to me that this was a really bad idea, and we quit.

For as long as we lived there, R.G.’s wife never could learn how to spell my first name. Every year her Christmas card was addressed to “Rundy Rucker,” which delighted the kids.

10. Sometimes the children liked to give me a taste of my own rebelliousness. Like when some carolers came by our house one Christmas in Lynchburg, and I called them to come see, they crawled to the door on all fours, barking, making faces, and peering out at the carolers as if they had no idea what was going on. The more I scolded them, the harder they barked and laughed.

11. The holidays and vacations rolled by. Sylvia’s parents would come to us for Christmas, and we’d visit them in the summers. Mom or Pop would visit for holidays, too, but never at the same time. Sometimes we’d have Thanksgiving at Embry’s farm, the jolly kids sitting at their own little table.

A family’s parade of days, with Sylvia and I leading our troupe of three little pigs. It seemed like it would never end, but now, looking back, it didn’t last nearly long enough.

12. Sylvia’s parents came over for our first California Christmas, and her father, Arpad, gave me the money to buy a used surfboard and a wetsuit from a local surf shop.

“This was Chang’s board,” said the proprietor, eyeing the battered but attractively priced board I’d selected. “He…” The guy’s voice trailed off. I never did find out what happened to Chang.

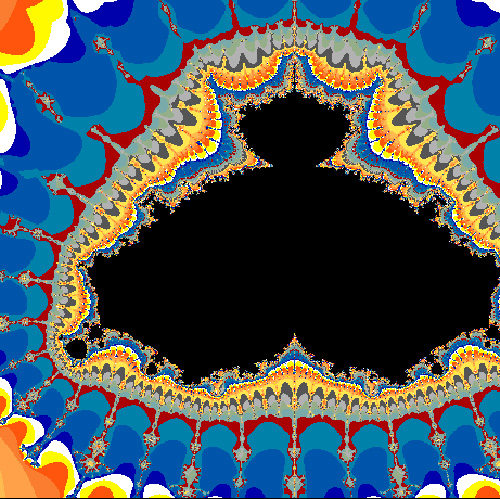

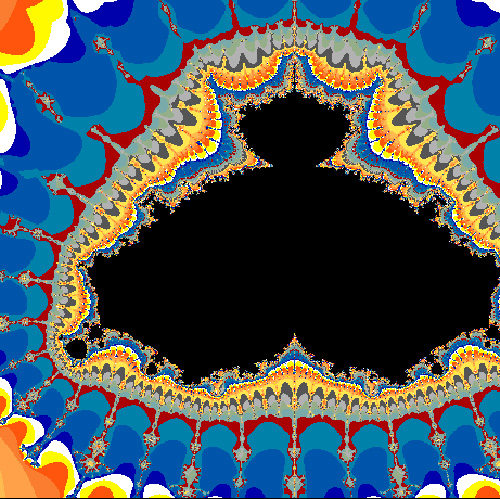

13. I gave a special Christmas talk and demo at the IBM research lab in San Jose. I jacked my cellular automata card into one of their IBM PCs and connected it to this monster projector that they had. Nobody else had computer projectors back then, so it was incredibly exciting for me to see my images get so big. I wanted to take off my clothes and let the sparkling little squares of the CA graphics slide across my bare skin.

The guys loved my realtime animated images, and when I was done I got more applause than I’d heard since being on a panel with star writer Larry Niven at a science fiction convention. But then some execs took me into a conference room and started asking me, “What are CAs good for?”

14. In search of a big third act for my novel, Saucer Wisdom, I flew to Spearfish, North Dakota, to meet up with an artist friend of mine who lives there. His name is Dick Termes, and he paints primarily on spheres. He says that right after Christmas is the best time for gathering “canvases” to paint on, he picks up lawn-scale ball ornaments on sale at K-Mart, covers them in gesso and paints on these marvelous six-point perspective scenes. What’s six-point perspective? Well, you can look it up—Termes has a video explaining it on the Web.

15. In Fiji, Sylvia and I snorkeled a lot too. Over and over, looking ahead, we’d barely notice things disappearing—zip!—into hidey-holes. Eventually, with much patience, we were able to see that the little phantoms were bright-colored, fringed cones—like tiny, spiral feather-dusters. A local told us these were the feeding organs of creatures called Christmas tree worms. They lived in the coral, and they grew themselves hinged trapdoors like thumbnails to cover their holes.

I thought again of my old idea of there being forms of life that move so fast that we never quite see them. Why not? Only a few centuries ago, we were unaware of the creatures that are too small for the naked eye to see.

Merry Christmas, and a happy 2009!