I’ll get back to “It from Bit” another day. Today I’m pasting in part of my ever-growing cumulative email interview, expanded by questions from Carmine Treanni for Quaderni D’Altra Tempi, an Italian SF review.

Today’s photos are from Brussels, 2002, where I was visiting The Flemish Academic Centre for Science and the Arts (VLAC) and working on Frek and the Elixir and my Lifebox book; I just came across the digital files for these images today.

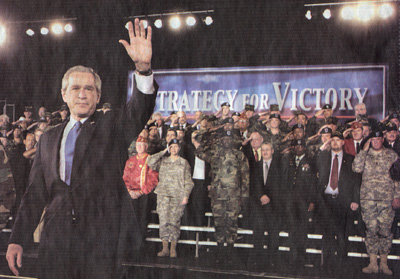

Oh, before the Brussels pictures, let’s start with a particularly evil-looking photo of El Chimp. I mean is this scary and retro and Orwellian, or what?

Q 171. You are considered to be among the founders of the Cyberpunk, together with William Gibson and Bruce Sterling. After twenty years from the birth of the movement, which are, in your opinion, the traces left by the movement in and out of the science fiction?

A 171. The whole style of dark, glittering, noir Hollywood films running from Blade Runner through the Terminator to the Matrix might be thought of as coming out of the cyberpunk sensibility. One topic beloved of cyberpunk was the fusion between humans and machines, and this is something you see in all these films. We were, if you will, the canaries in the coal mine, noticing the first fumes of mankind’s accelerating roboticization.

Films, however, miss the druggy, antiestablishment satire that lies at the core of cyberpunk. But other writers have picked up the torch of nihilistic humor and apocalyptic speculation. I think of, for instance, Charles Stross’s Accelerando of 2005.

Q 172. With your four novels belonging to the Ware series, you gave birth to a real revolution in the robot concept of science fiction. How do you think that robotic technology will develop in the human future?

A 172. When I visit a lab and see the actual state of cutting-edge robotics, I’m always a bit disappointed. It’s still so flaky and cobbled together. I think it could be a hundred years until we get seriously good humanoid robots. There’s also the question of whether we really need the humanoid robots so beloved in SF. After all, we already have too many people, and people cost next to nothing to bring into being. But it’s work to be around other people, and some geeks dream of being able to get machines that do all the useful things that humans do without including the troublesome things such as: making you feel empathy and sympathy and pity for them; possibly becoming annoyed or even rebellious; not being something you simply turn off and throw away when you’re done.

Laid out like this, we can see how really screwed-up is our desire for robot slaves! In my Ware books, of course, as soon as the robots got as smart as people, they were as much trouble as people.

In terms of actual technology, I’ve always been fascinated by the notion of piezoplastic, that is plastic that flexes like muscles. Brittle gear-and-spring robots seem so unnatural. Putting it quite baldly: What good is a humanoid robot who you wouldn’t want to have sex with? I really get into that in my book Freeware, where there’s people sexually obsessed with soft robots.

An alternative to smart-plastic robots may be biotechnology. If you talk about a biotech robot, you really bring the fundamental contradiction into relief: geeks want to make a person that is a “robot” in the sense of not having a soul or deserving any empathy. Sometimes SF movies have treated this theme, with the underclass being clones. But, again, with overpopulation, this exercise is fundamentally pointless. Humans already know about enslaving each other, and we already know it doesn’t work out as a good thing.

In a more practical vein, I think we will see better and better AI in our appliances. Certainly the self-driving car will come into being, assuming there’s away around the crippling law-suits that will ensue when the vehicles occasionally malfunction. Certainly our computers will learn to speak, to understand speech, and to fake something like a human personality in conversation.

One of the best ways to have a program imitate a human is simply to give it an enormous database of texts that one person has written or said. In this case, a good search engine can replace having to create real AI. The program simply looks up an appropriate answer. I call this kind of device a “lifebox.”

Q 173. Could you, please, talk about your new nonfiction book, The Lifebox, the Seashell, and the Soul?

A 173. The title itself is a dialectic triad. The Lifebox thesis is that there can be computer models of human minds, the Soul antithesis is that I feel myself to be a vibrant energy-filled being and not a machine, the Seashell synthesis is that the computational patterns found on certain kinds of seashells are examples of the gnarly deterministic-but-unpredictable computations that could indeed inhabit my skull.

I might mention that the subtitle is What Gnarly Computation Taught Me About Ultimate Reality, the Meaning Of Life , and How To Be Happy. You can find out more about the book on my Lifebox website.

I think we’re presently in the midst of a third intellectual revolution. The first came with Newton: the planets obey physical laws. The second came with Darwin: biology obeys genetic laws. In today’s third revolution, were coming to realize that even minds and societies emerge from interacting laws that can be regarded as computations. Everything is a computation.

Does this, then, mean that the world is dull? Far from it. The naturally occurring computations that surround us are richly complex. A tree's growth, the changes in the weather, the flow of daily news, a person's ever-changing moods — all of these computations share the crucial property of being gnarly. Although lawlike and deterministic, gnarly computations are — and this is a key point — inherently unpredictable. The world's mystery is preserved.

I mixed together anecdotes, graphics, and fables, in the book to tease out the implications of this new worldview, which I call “universal automatism.” Looking at reality as a bunch of computations reveals some startling aspects of the everyday world, touching upon such topics as chaos, the internet, fame, free will, and the pursuit of happiness.

I tried to make this tome more than a popular science book, a philosophical entertainment that teaches us how to enjoy our daily lives to the fullest possible extent.

Q 174. What is your definition of science fiction? How do you consider and see the current status and the prospects of science fiction?

A 174. Science fiction is writing that analyzes some fast-changing aspect of society by extrapolating current trends into the future or into an alternate world. Traditionally science fiction has certain standard tropes that it uses, but new ones are being developed all the time — I’m thinking of things like blaster guns, spaceships, time machines, aliens, telepathy, flying saucers, warped space, faster-than-light travel, holograms, immersive virtual reality, robots, teleportation, endless shrinking, levitation, antigravity, generation starships, ecodisaster, blowing up Earth, pleasure-center zappers, mind viruses, the attack of the giant ants, and the fourth dimension. I call these our “power chords,” analogous to the heavy chords that rock bands use.

When a writer uses an SF power chord, there’s an implicit understanding with the informed readers that this is indeed familiar ground. And it’s expected the writer will do something fresh with the trope.

This implicit contract isn’t honored by mainstream writers who dip a toe into “speculative fiction”. These cosseted mandarins tend not be aware of just how familiar are the chords they strum. To have seen a single episode of Star Trek twenty years ago is sufficient SF research for them! And their running-dog lickspittle lackey mainstream critics are certainly not going to call their club-members to task over failing to create original SF. After all (think they), science-fiction writers and readers are subnormal cretins who cannot possibly have made any significant advances over the most superficial and well-known representations, and we should only be grateful when a real writer stoops to filch bespattered icons from our filthy wattle huts.

I’m exaggerating for comic effect. (And this rant is lifted from a Readercon address I gave in 2003. Note the ongoing lifebox simulation of me actually being alive…) Really, SF is doing quite well, although of late it seems as if fantasy is eating our lunch. But I’ve been hearing gloom-and-doom for my whole career as an SF writer. I’m just happy I continue being published and read. Maybe someday they’ll start making movies of my books and I’ll get the big money.

Q 175. Please tell me something about the writing process when elaborating a new novel.

A 175. When I start, I always have in mind a few crucial situations or devices that I’m eager to explore and depict. These ideas arise to some extent spontaneously, and to some extent from thinking about scientific and social ideas that interest me.

Once I have a vague idea of the book’s theme, I begin working on figuring out the characters, the geography, the society, the tone, the point of view, the story arc, the physics, and, above all, the plot outline.

I write about all these ideas in a notes document that I develop in concert with my novel; usually my notes documents end up nearly as long as my books. I post each of the notes documents online when the corresponding book is published.

The virtue of having a notes document is that then there’s something I can work on when I don’t quite feel ready to write the novel.

When a book’s going well, I can average about a thousand words a day. When I get my thousand words, I print it and go to the coffee shop and reread it and mark it up, then type it in again and repeat the process. I might cycle through a given section three times in a day, and the next day maybe one more time and then I move into the next section. I have more about all this in my document “A Writer's Toolkit.”

I tend to be somewhat anxious when I work, worrying I won’t be able to get things to come out right. In general, I worry too much.

November 22nd, 2005 at 2:38 am

First, thank you for “A Writer’s Toolkit”.

It reminds me of “Code Complete” or “The Pragmatic Programmer” because of how it shows the nuts and bolts of the process.

Fyi, I think there’s an error on page 11:

—-

For now instead of an (A->B) scene, you now have (A->C) and (C->A).

—-

Should be:

—-

For now instead of an (A->B) scene, you now have (A->C) and (C->B).

—-

Thanks again for the knowledge!

Hard gotten, generously given, much appreciated.

karl

November 22nd, 2005 at 11:12 am

Rudy, if a lifebox had good software, would it be able to write more Rucker books? You know you’ve probably got fifty more book ideas imbedded in your musings just on this blog. If the box could carry out these intentions, modifying sentences to explain the idea, it would be on the road to a kind of AI…. Rudy Racter?

November 24th, 2005 at 12:56 pm

“let’s start with a particularly evil-looking photo of El Chimp. I mean is this scary and retro and Orwellian, or what?”

Umm. No.