Today’s post is the transcript of a short email interview with me by Simone Lackerbauer, who’s at the University of Paris working on a thesis about Mondo 2000 and cyberculture. The numbering of the questions and answers (326, 327, and 328) extends the numbering in my unified interviews file, available as a PDF online.

Q 326. You have been writing mathematics books and SF novels, you have published software packages, and you are a painter. How much of your professional activity is related to formal education, how much was just learning by doing or by observing (as with your recent “Stolen Picasso” painting? Do you think there is a difference between the value of things we learn by tinkering and experimenting and the things we learn at school or at university?

A 326. Although I have a Ph. D. in mathematics, I never took a course in computer science or in writing. So I am in many ways self-taught.

I would hasten to add that my years of education did make a difference to me, even in the areas in which I never had any formal studies. A liberal education prepares you to study, to learn, and to form ideas of your own. The intense, focused effort of writing a graduate-level dissertation gives you a sense of how to think hard about a single topic over a sustained period of time.

Writing was the craft I wanted to learn the most, and I got my first start at it simply by writing a lot of letters to my college friends. I used a typewriter, just as I imagined professional writers would do. I had an Olivetti portable. Later, after grad school, I got a rose-colored IBM Selectric, a lovely machine, currently enshrined in my basement.

Part of learning to write is a matter of learning to imitate the writers that you admire. I read a lot, and, over the years I imitated Hemingway, Kerouac, Terry Southern, Pynchon, Burroughs, Vonnegut, Phil Dick, Robert Sheckley and many others. Thanks to some fortunate fluke of my mental makeup—and to years of practice—I find it fairly easy to mold words into patterns that I like.

If you read a lot, you develop a large inner library of words and phrases that you love, not to mention a repertoire of story twists, attitudes, and styles of thought. The inside of a working writer’s head is like the backstage wardrobe room at a theater. In your apprenticeship you stock the wardrobe room, then you began assembling costumes from it, and perhaps at some point you’re designing entirely new garments of your own.

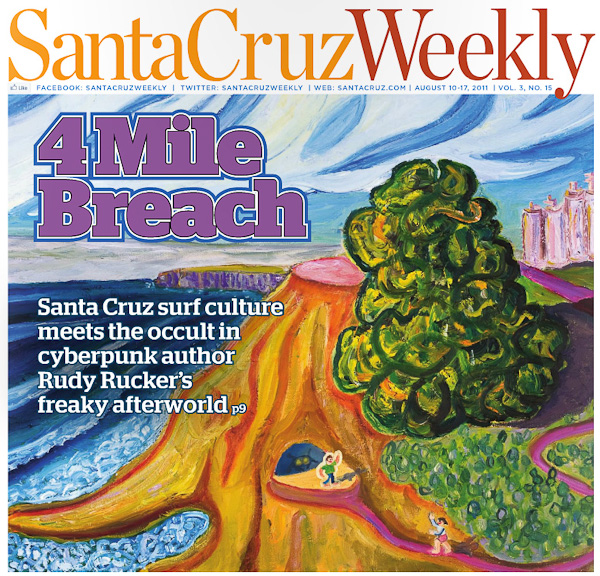

I’m still very much a beginner at the craft of painting, but the process of maturation seems somewhat similar to that of writing. You learn, you copy, you create. I’ve been going to museums and galleries to look at paintings for forty or fifty years and, as with writing, I have a mental store of effective techniques and imagery that I’ve observed. Unlike with writing, I’m by no means a natural painter, and creating images that I want is time-consuming. But eventually I can get some things that I like—painting over things, rubbing out false steps, revising the outlines, daubing on new layers to change the shades. The one thing that works to my advantage as an amateur painter is that I have a visual imagination, so I have a good supply of images I want to see.

Touching on another question that you raise—we place the greatest value on the things we discover ourselves. School is really a matter of teaching you how to go about your investigations. The real knowledge consists of the things you find on your own.

Q 327. Someone not familiar with the field of computer science might think it is based on logic and algorithms. Is there anything about computer science that cannot be taught formally? What are the creative aspects of computer science?

A 327. Computer science is a multifarious field—one distinction is between theory and practice. It is in fact possible to write a Ph. D. thesis in computer science without ever writing any substantial programs—a dismissive description of such a thesis is: “proving that two ugly Turing machines are equivalent.” That’s on the pure theory side of things.

I was a CS professor for about twenty years, and I was always more interested in practice than in theory. That is, I enjoyed crafting programs that do things that are in some way interesting. And I based my theoretical notions on these new programs that I’d made.

In particular, I always liked writing what I call gnarly programs. These involve intricate colored shapes on the display screen that may come to life and dance around. I’m thinking of cellular automata, fractals, chaos, artificial life, and videogames.

I often taught a class on software engineering in which I had the students write videogames. It’s very hard to write a lively videogame from scratch—there are exceedingly many technical details that you have to get right. Over the five years, I managed to craft a textbook, Software Engineering and Computer Games, with a framework of C++ code that my students could build upon to get their own programs going, with plenty of little critters racing around. (The book and the software framework are now online for free download. )

I used to tell my software engineering students that learning to program is about learning how to make mistakes faster. Hardly any program ever works immediately. There’s always a mistake in it, something wrong. And you have to find the bug and fix it. And then there’s a new bug. And you have to fix that. Faster and faster.

Some textbooks make it sound as if software engineering is a formal process of making out lists of specifications, milestones, and the like, the process is also an experiential hands-on endeavor. You don’t ride a bicycle by making out lists of part numbers. You have to get on it and lurch around.

There are any number of ways to be creative in CS. In terms of theory, you might come up with a new higher-level way of thinking about computations. In terms of practice, deciding what kinds of programs to create can be creative. Much creativity (and low cunning) comes into play in finding ways to make one’s programs run faster. And designing a program’s interface is an artful process as well.

Just as is the case for writers and painters, programmers will often find that their projects are mutating while they work on them. Certain pathways close up, and newer opportunities emerge. At some point it can feel as everything you see all day long is in some way part of the creative process—as if everything is helping you to get the project done. This is known as communing with the Muse. And, make no mistake, there is a Muse of programming as well as there are Muses of writing and painting.

Q 328. How would you personally define “cyberculture” and is it what you thought it would be like twenty or thirty years ago? How has the relationship to personal computers, smartphones and other gadgets changed? In what ways is cyberculture relevant for computer science?

A 328. I feel I should pause here and dispel any idea that I’m primarily a computer scientist. That’s not the case. Although I was a professor of computer science from 1986 to 2004, and worked as a software engineer at Autodesk in the late 1990s, these were day jobs for me, that is, ways to make money while I pursued my true career—which is writing science fiction novels and popular science books.

The people with the 1990s magazine Mondo 2000 were among the first to form a notion of cyberculture. They picked up on the McLuhanesque notion that the spread of computers was changing our culture. William Gibson’s novels involving cyberspace were a big influence as well, as was the burgeoning interest in virtual reality, not to mention the spread of the internet.

In cyberculture both our social lives and our personal images are to some extent delocalized. In part, you and your acquaintances are your blogs, your web pages, your social network posts, your emails. As long as you have access to computer or a smart phone, you can plug into cyberspace.

These days you feel impaired when you can’t access the internet—you feel like a nearsighted person who’s misplaced their glasses, like a deaf person without a hearing aid, like a musician wearing heavy gloves.

The full-immersion computer-graphical techniques of virtual reality haven’t caught on to the extent that was predicted. People are content with the highly detailed worlds of their videogames. The human mind is so labile that you can in fact project yourself into these worlds without having to wear goggles with video screens.

Here in 2011, we’re at an awkward point in terms of our devices—you see people staring at the very tiny screens of their smart phones and tapping on the even tinier keys of their virtual keyboards. Clearly this is a defective interface, which may be replaced by voice recognition techniques or by stick-on sensors that might read the subvocalizations in your throat or possibly the brain waves at the base of your skull.

Certainly it’s good for the field of computer science to have our daily reality so fully imbued with cyberspace. There’s no end to the problems and applications that arise. At some point we might expect to have every physical object be represented in the internet in one way or another.

And, of course, all of this provides rich fodder for science fiction novels such as my recent duology Postsingular and Hylozoic. In these books reality is fully subsumed into a telepathic internet, and every object becomes alive. It may happen yet!