I was up at Lucasfilm in the Presidio in San Francisco on Thursday, May 18, 2006, to give a talk on “Gnarly Computation.” Right outside the front door, they have a nice fountain with Yoda on top. I’ve always had mixed feelings about Yoda. I guess mainly I love him. He reminds me of D. T. Suzuki, the Zen sage.

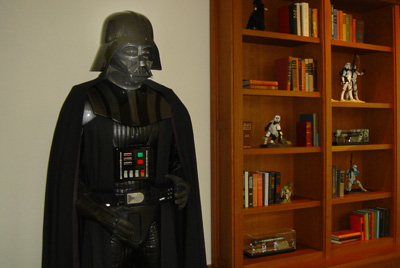

The building is all decked out in California Craftsman style, very impressive. Mine host Darth Vader was there to greet me.

Lucasfilm is an umbrella organization which owns Industrial Light and Magic(IL+M), a special effects group, plus LucasArts, a game company. Adn of course Lucasfilm handles George's projects like Star Wars and Indiana Jones. The Industrial Light and Magic office used to be in San Rafael, and they had it hidden in a complex of buildings with the entrance door marked as “Kerner Optical.” The reason was that now and then demented fans showed up looking for Yoda and Darth. I think once one of them even got run over by a car. “Hey, I though that was a hover car, so I could lie down under it!” So it seemed better to have the company incognito. You can find them easily now, but they do have good security, and Yoda's right outside on the fountain anyway, so no prob.

I was up at the old IL+M in 1993, to write a Jurassic Park inspired article for Wired magazine. I think the model shop is still in San Rafael; it’s all electronic down at the Presidio now. This funky thing was wrapped in rubber and used as a dinosaur!

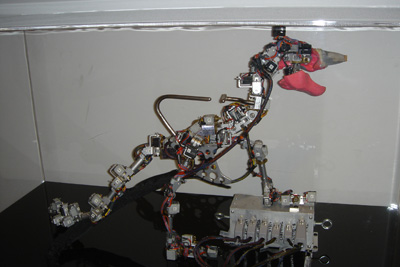

There’s a bunch of old models kicking around the building; this one’s from Ghost Busters. In a way, it’s sad that they don’t make so many physical models anymore.

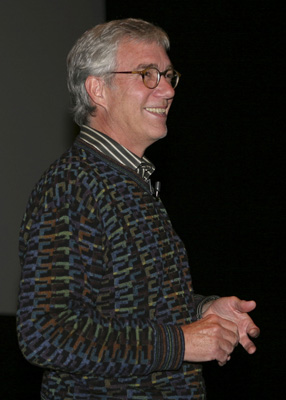

I gave my talk in a big auditorium. A good crowd showed up, maybe fifty or sixty people.

Tina Mills, the Manager of Image Archives at Lucasfilm took some nice pictures of me.

Click on the icon above to get to Rudy Rucker Podcasts, and here is a PDF of the slides of my PowerPoint. It’s quite similar to the talk I gave at Fresno State a few weeks back, though the questions at the end are different, and during the talk I have some remarks on using these ideas for game and effects design.

After the talk, I went and had lunch with Kate Shaw who organizes the talks there, also John Olmstead, the IL+M engineer who had the idea of inviting me, and Brian Baird, an engineer in LucasArts working on some cool projects like self-modifying games that generate their own action scenarios.

John told me they'd been rendering water for the new Poseidon movie, and they'd needed to use all 5,000 processors on the grounds at once, and even those were lagging. Water is hard. Nature is way ahead of the beige boxes.

This is Brian and John with the Golden Gate bridge visible out the cafeteria window. By the way, I heard that LucasArts wants to double their size, so if you’re looking for a job in the game industry, this seems like a good place to check out.

Tina took a nice picture of me outside. I just got some new glasses last week.

After I was done, I walked around the grounds a little. Here’s a statue of Eadweard Muybridge, the guy who took those zoopraxiscope multiple frame pictures of people moving around. (Have you noticed that, more and more often, the best link for a topic is in the Wikipedia? Way to go Wikkers.) That’s the Palace of Fine Arts / Exploratorium in the background. When he was born, his name was Edward, but he adopted the Eadweard spelling just for kicks. I used that name in Frek and the Elixir.

I said farewell to R2D2 and C-3PO and went home. Oh, I should mention that I saw some nice demos up in the LucasArts labs. They're making, like, wood or marble out of virtual particles, so every time you smash up a crate it smashes differently. They had a really cool looking giant rubber Star Wars plant from some obscure planet I forget. This engineer kept hurling virtual R2D2's at the plant and it shook so sexy and gnarly and chaotic. Seek the Gnarl!