[Excerpts from my memoir, Nested Scrolls.]

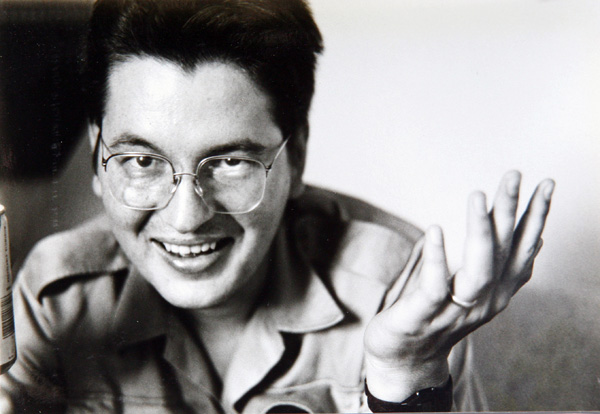

I started getting mail from a younger writer in Texas called Bruce Sterling. He’d written glowing reviews of Spacetime Donuts and White Light in a weekly free newspaper in Austin—he was one of the very first critics to appreciate these books. Soon after this, Bruce began publishing a zine called Cheap Truth.

Bruce loved all things Soviet—it wasn’t that he was a Communist, it was more that he dug the parallel world aspect of a superpower totally different from America. He spoke of Cheap Truth as a samizdat publication, meaning that, rather than printing a lot of copies, he encouraged people to Xerox their copies and pass them from hand to hand.

Reading Bruce’s sporadic mailings of Cheap Truth, I learned there were a number of other disgruntled and radicalized new SF writers like me. The Cheap Truth rants were authored by people with pseudonyms like Sue Denim and Vincent Omniaveritas. I was too out of the loop to try and figure out who was who, but I took note of the authors being hyped: Bruce Sterling, Lew Shiner, William Gibson, Pat Cadigan, John Shirley, and Greg Bear. I couldn’t actually find books by many of these people in Lynchburg, Virginia, although Bruce did mail me a couple of his novels, including Involution Ocean, a delightful take on Moby Dick which features dopers on a sea of sand. This work has some transreal qualities, and I liked it lot, including its unexpectedly maniacal ending…it’s a shame the book is currently so hard to find.

Sterling’s zine, Cheap Truth¸ didn’t have any particular name for the emerging new SF movement—it wouldn’t be until the next year that the cyberpunk label would take hold. I got together with Sterling, William Gibson, and Lew Shiner in September of 1983. We partied together at a world science fiction convention in Baltimore—they’d all read my new novel The Sex Sphere, which had just been published by Ace.

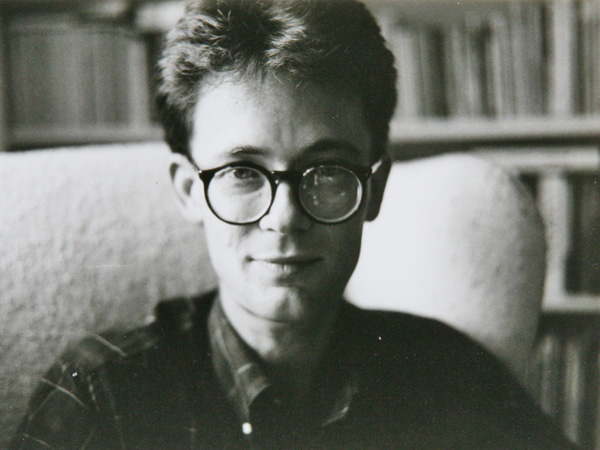

Gibson was an impressive guy from the start. He was tall, with an unusually thin and somewhat flexible-looking head. When I met him at one of the con parties, he said he was high on some SF-sounding substance I’d never heard of. Perfect. He was bright, funny, intense, and with a comfortable Virginia accent.

Back home in Lynchburg, I spent a day at my downtown office as usual and drove home in our black and white Buick, resplendent in the Hawaiian shirt that Sylvia had sewn for me. And there were Gibson, Sterling and Shiner on our front porch, along with Bruce’s wife, Nancy, and Lew’s friend, Edie. They’d decided to drive down after the convention.

These guys were all a bit younger than me—I was thirty-seven by now. To some extent they looked up to me. I was thrilled to join forces with them, it felt like being an early Beat.

I’d meet the other canonical cyberpunk, John Shirley, two years later, when we were both staying with Bruce and Nancy Sterling in Austin, Texas, in town for a science fiction convention that was featuring a panel on cyberpunk. John was a trip. When I woke up on Sterling’s couch in the morning, John was leaning over me, staring at my face.

“I’m trying to analyze the master’s vibes,” he told me.

The antic SF personage Charles Platt was there in spirit, he’d mailed Bruce a primitive Mandelbrot set program that he’d written in Basic. We’d set the program to running on Bruce’s primitive Amiga computer, and a couple of hours later we’d see a new zoom into the bug-shaped fractal—chunky pixels colored in blue, magenta and cyan.,

As we walked around Austin together talking, John had a habit of picking up some random large stone from a lawn, lugging it over to me, and putting it into my hands. Sometimes I’d be so into the conversation that I’d just carry the rock along for a few steps before noticing it.

Naturally we’d get high in the evenings. I recall driving a rented Lincoln around town with John. He was riffing off my book Software, leaning out of our car window to scream at the Texas drivers, “Y’all ever ate any live brains?”

The writers on the Cyberpunk panel were me, Shirley, Sterling, Lew Shiner, Pat Cadigan, and Greg Bear. Gibson couldn’t make it. The moderator—whose name I’ve forgotten or never knew—hadn’t read any of my work, and was bursting with venom against all of us. He represented the population of SF fans who are looking for a security blanket rather than for higher consciousness. For his ilk, cyberpunk was an annoyance or even a threat. He’d slid through the 1970s thinking of himself as with-it, and cyberpunk was yanking his covers.

To my eyes, the audience began taking on the look of a lynch mob. Here I’m finally asked to join a literary movement, and everyone hates me before I can even open my mouth? Enraged by the moderator’s ongoing barrage of insults, John Shirley got up and walked out, followed by Sterling and Shiner. But I stayed up there. I’d traveled a long distance for my moment in the sun.

“So I guess cyberpunk is dead now?” said Shiner afterwards.

I didn’t think do. Surely, if we could make plastic people that uptight, we were on the right track. That’s what the punk part was all about.