I’m still working on my novel, Turing & Burroughs, one scene at a time.

I need a word for the people who’ve been taken over by skugs. They aren’t exactly skugs themselves; I think of a pure skug as being one of those globs that doesn’t necessarily have any human personalities inside it. When a skug eats you, you are a skug, yes, but you’re also to some extent yourself, in that you can look like yourself and act like yourself.

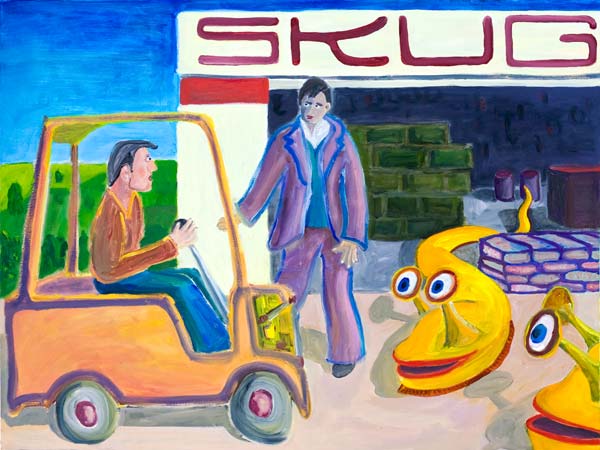

“Turing and the Skugs”, 40″ x 30″ inches, Oct 2010, Oil on canvas.” Click for larger version. The painting itself will be on display as part of my show at Borderlands Cafe on Valencia St. in SF, CA, until December 1. More info on my paintings site.]

I’ll go with skugger. “He’s a skugger,” sounds right. “She’s a skugger, too.” There’s an echo of slugger, which suggests a heavy hitter. I do like the er ending, which suggests an on-going activity. Like “bopper” in the Wares. Bopping it up. Skugging it up.

Speaking of nomenclature, I think I’ll use skug as a verb to describe the act of turning someone into a skugger. “They skugged her.” “I got skugged, too, man. It’s great.” I think of the lyrics to Bob Dylan’s song, “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35”. Here’s a verse with “skug” instead of “stone,” and with the second to last line changed for the sake of the rhyme.

Well, they’ll skug ya when you’re walkin long the street

They’ll skug ya when you’re tryin to keep your seat

They’ll skug ya when you’re walkin on the floor

They’ll skug ya when you’re walkin to the door

But I would not feel like such a grub

Everybody must get skugged

We can suppose that the skuggers like to band together. They’re an endangered minority, at least for now. And I think that it’ll soon be clear that they’re bent on world domination, as befits their role as objective correlatives for the 50s bogeymen: intellectuals, artists, racial minorities, communists, dope-fiends and homosexuals. “Everybody must get skugged.”

As the book goes on, I want Alan to realize that the skugs have very powerful minds, more so than he anticipated. Their high intelligence is due to (i) parallelism, that is, they’re using each organic cell as a computing unit and (ii) connectivity, that is, via radio waves, they’re in touch with each other, and with as much of the human data-base as is being broadcast on radio, TV and telephone.

When imagining the skug experience of hearing all the radio stations at once, I think of Patti Smith’s album, Radio Ethiopia…