I recently read an advance copy of a great book by my friend Richard Tieszen. It’s called Simply Gödel. It’ll go on sale in mid-April, but you can pre-order now if you like. The book is a remarkable achievement—a handy guide with the impact of a philosophical tome. It’s all here: elegantly lucid discussions of Kurt Gödel’s epochal discoveries, a sympathetic account of the eccentric genius’s life, focused discussions of his encounters with his astonished peers, and a visionary peek into the future of mathematics, philosophy, and the on-rushing specter of robots with minds. A compact masterpiece, brimming with fresh revelations.

I’ll discuss some of my thoughts sparked by Simply Gödel today, adding some of my paintings to the illos, including two new ones.

As I’ve mentioned in my blog posts “Memories of Kurt Gödel” and “Conversations with Kurt Gödel,” in 1972 I had a couple of long talks with Gödel in his office at the Institute for Advanced Study. He made a huge impression on me. It goes almost without saying that he was the most intelligent person I will ever meet. Even though he was, at some lower levels…eccentric.

“The Wanderer,” acrylic on canvas, 24 ” x 18 “, September, 2008

How so? Gödel had very unusual views on the nature of reality. He firmly believed that there are indeed higher levels and higher beings—things like ghosts or demons. Indeed, he felt that a person is in some sense an extradimensional being that might be called a monad, after Leibniz’s use of the word. A monad affects the physical world, but it’s not embedded in the spacetime framework. A bit like a soul.

At less philosophical levels, Gödel could be paranoid. He worried that poison gases emanated from his refrigerator or from his furnace. He worried that strangers might be assassins who planned to kill him. He worried that his food was poisoned—and he preferred not to eat anything unless his long-suffering wife Adele had tasted it first.

But these aspects of the man weren’t apparent when he was talking about mathematics, science, philosophy, and mysticism. To me, he seemed like a man of knowledge and wisdom, profoundly so.

“Origin of Life” acrylic on canvas, March, 2017, 30” x 20”. Click for a larger version of the painting.

Shown above is a painting of me talking to Gödel in 1972. Well, actually it’s a painting of an abstract image based on a cellular-automaton screen I recently captured, characterized by having double scrolls known as Zhabotinsky patterns. See my previous post, “Still Seeking the Gnarl,” for more about these CAs. These patterns occur naturally in certain chemical mixtures, and they could have played a role in the origin of life within the primordial soup. So I called it “Origin of Life.” But, who knows, maybe it is me and Gödel. Monads in an extradimensional space of phenomenological impressions. But which one is me?

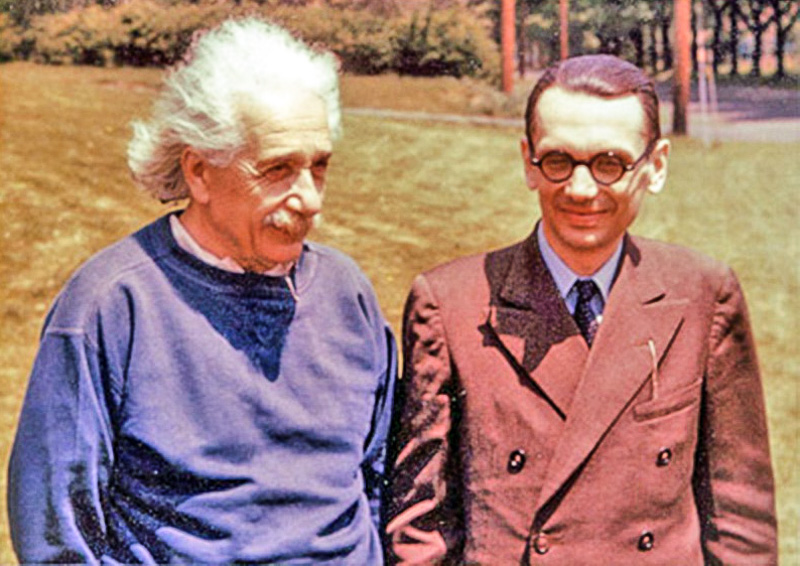

Gödel was Einstein’s best friend during the physicist’s later years in Princeton. Why? Probably Because Gödel was the one person who could readily understand what Einstein was talking about. And perhaps because both of them had made a priori intellectual discoveries that changed humanity’s way of seeing the world. But Einstein wasn’t above teasing his younger friend. Here’s a quote from Ernst Gabor Strauss, taken from Rebecca Goldstein, Incompleteness: The Proof and Paradox of Kurt Gödel.

Reading Tieszen’s great Simply Gödel got me thinking about all these things again. If we have souls and telepathy, maybe Gödel is still talking to me. Helping me understand Tieszen’s book, as far as it goes. Something in the book that strikes me as particularly interesting is the notion that, in his later years, Gödel was looking for a way to justify his belief that we have a direct perception or intuition about mathematical objects. He felt we could “see” even such objects as outré as transfinite sets such as the cardinal alef-one, or the continuum of all real numbers between zero and one. You want to know if these two sets have the same size? Focus. Look harder…

Immanuel Kant famously said that the “real” objects around us are so-called noumena, and we know them only at second-hand, that is, via the phenomena given by our senses…sounds, images, touch sensations, smells, etc. And later the philosopher Husserl started talking about phenomenology, which might mean the practice of taking your sense impressions as in some sense external to you as well. Like, rather than blundering around banging our shins on noumena, we’re spacing around in a cloud of phenomena. Husserl isn’t super clear about any of this. He strikes me as something of a bullshitter, never writing one word when twenty will do. But I feel there’s a fertile acorn sprouting beneath his great load of words. With an oak to emerge.

“Topology of the Afterworld,” acrylic on canvas, 40 ” x 30 “, August, 2009.

Trying to imagine being a phenomenologist, I let go of my ordinary stance of being an object among objects. As Husserl would put it, I bracket this mode of thought, that is, put it on hiatus. (There’s even a short Wikipedia article about phenomenological bracketing!)

So I frikkin’ bracket the whole issue of what is reality. I’m a monadic focus point amid phenomena. I’m not watching things, I’m kicking it back a level, I’m experiencing phenomena. It’s like an exercise in mindfulness. Just focus on the flow of sights and sounds and touch and weight and don’t try to interpret them or see them as objects, just take them for what they are…phenomena.

It’s so hard to “keep up” with the onrushing flow sensations, one is continually tempted to dive down into associative chains. But when I can do it for a few minutes, it gets me high, and that is, after all, the end goal of philosophy (at least to this reprobate’s mind). And you can jack up your phenomenological awareness to a “transcendental” level and treat your thoughts as phenomena as well.

Looking at the odd 3/4 moon on the horizon last night, rotten looking, moldy as an overripe cantaloupe that seeps smeely fluid, I advised to Sylvia that we bracket any thought about the Moon’s physical nature, and merely focus on the look of the moldy moon.

I think for the rest of the week I’ll make a habit, of saying I’m bracketing whatever is going on around me at any given time. Kind of a Woody Allen thing to do. He loves joking about higher philosophy.

Speaking of phenomenology, Georg Hegel is my great-great-great-grandfather, and one of his best-known works is Phänomenologie des Geistes, which we call either The Phenomenology of Mind or The Phenomenology of Spirit. Not that, so far as I know, Hegel’s notion of phenomenology has much to do with Husserl’s. I’ve been trying to read this book since I was in high-school, and so far I’ve never gotten beyond the preface. But there is one passage in the preface that I’ve grown to love. Especially the sentence I italicized.

A building is not finished when its foundation is laid; and just as little, is the attainment of a general notion of a whole the whole itself. When we want to see an oak with all its vigour of trunk, its spreading branches, and mass of foliage, we are not satisfied to be shown an acorn instead. In the same way science, the crowning glory of a spiritual world, is not found complete in its initial stages. The beginning of the new spirit is the outcome of a widespread revolution in manifold forms of spiritual culture; it is the reward which comes after a chequered and devious course of development, and after much struggle and effort.

I take this passage to express an idea popularized by Stephen Wolfram in his A New Kind of Science. And this is the notion that, in the realm of computation, we can have incredibly rich and complex patterns that are in fact based on extremely simple little rules. The Mandelbrot set is a classic example of this. And, if you think of biological growth as a type of computation, the tree is indeed the “output” of the tiny acorn program. One of the most interesting places to see small rules making cool patterns is in the world of cellular automata.

“Antarctica” acrylic on canvas, March, 2017, 24” x 20”. Click for a larger version of the painting.

This is another recent painting of mine based on cellular automata. The image also dovetails with my ongoing obsession with “At the Mountains of Madness,” which is H. P. Lovecraft’s story about the lost ancient city in Antarctica. You can see the image in that same recent “Still Seeking the Gnarl” post. I think of this painting as an aerial view of the ruined city. Synchronistically, the Capow pattern happened to have a shape like the head of a penguin. Working the phenomena. But maybe that’s possible. Maybe if you get phenomenological enough you can be dancing with the universe, in synch with reality’s higher cosmic patterns.

But if I’m living in some sense to the side of the so-called physical world, then what am I? As I was hinting at above, Gödel seems to want to say that he’s a monad, in Leibniz’s sense of the word. Gabriella Crocco of the university of Aix/Marseille wrote a great 2013 paper about Gödel, Leibniz, and monads, entitled, Gödel, Leibniz and “Russell’s mathematical logic”. The phrase “Russell’s Mathematical Logic,” refers to one of Gödel’s papers.

As another good philosophical resource see my Paris philosopher friend Mark van Atten’s excellent, “Monads and Sets. On Gödel, Leibniz, and the Reflection Principle” from 2009. Mark was my nearly constant companion when I was a visiting scholar in Brussels.

Tieszen’s Simply Gödel further discusses Gödel’s rationalistic Platonism, and gets into the issue of having direct phenomenological perceptions of transfinite sets, which is something which Gödel hinted at in his essay, “What is Cantor’s Continuum Problem,” and which G also discussed with the philosopher Hao Wang, and mentioned when talking to me. One the appealing things about Tieszen’s book (as well as Crocco and van Atten’s papers) is that, as a computer programmer might say about efficient low-level code, they “stay close to the metal.” Meaning that, rather than launching into overly wispy imaginings of what Gödel might have meant to say, these philosophers stick to actual quotes from the man’s published and unpublished papers, the more fragmentary remarks in his archives, and of others’ records of conversations with him. There’s more than enough here to launch the wildest fantasies.

“Thirteen Worlds,” acrylic on canvas. 24″ by 18″. January, 2009.

Getting back to monads, back in 2004, I read the whole of Leibniz’s short book, The Monadology. It’s pretty close to being incomprehensible. It’s way out there. Leibniz seems to say that our universe is an assemblage of “monads” which reflect each other, and each monad has the whole world inside it. Naturally, it struck me that an idea this crazy ought to be used in an SF story. And—here’s the literary surrealist-in-action part—as soon as I thought of that, I immediately thought that each monad should resemble a knobby giraffe. With brindle patches on it. And in 2016, I wrote an SF tale called “The Knobby Giraffe” for Lightspeed magazine.

But I still feel like I’m missing the mark in my conception of monads.

Something more to think about. Anyway, thanks again to Richard Tieszen and Simply Gödel for getting all these wild thoughts churning in my head!

March 17th, 2017 at 7:34 am

“I think for the rest of the week I’ll make a habit, of saying I’m bracketing whatever is going on around me at any given time.” When I saw this I had to laugh, given that this week the NCAA Basketball Tournament will be underway in earnest. So this will be Rudy Rucker’s “brackets”. Also, I noted a tiny typo in your text, calling the moon “smeely” instead of smelly. I like the replacement word better. I hope you keep it. 🙂

All that said, whenever I read the “phenomenology” stuff from Western philosophers, I think of the Vedic scholars, and note that they had this “bracketing” process down pat something like a thousand years ago. It’s called practicing Witness Consciousness. Or in modern parlance, Mindfulness. The Vedics say that if you practice it skillfully enough, you really do experience bliss. I am not sure that is the point of modern Western philosophy, but it does seem to be the end result of ancient Eastern meditation practices.

Thanks also for your comments about Husserl’s wordiness. I used to tell my friends that reading Husserl was a little like smoking a legal intoxicant. Just inhale enough that you feel overwhelmed and confused, then let out a long belly laugh and smile.

But he had his good points too. Thanks for describing them here.

Best to you this week. 🙂

March 17th, 2017 at 10:00 am

I have an intuitive understanding of monads, but an intellectual one, no. Same thing with phenomenology.

I did have an experience (chemically assisted) where I was able to see thoughts as bubbles in space, and could see it approaching, then experience the thought, then it vanished.

Éirinn go Brách!

March 17th, 2017 at 2:28 pm

Thanks, womans_voice and Eric. Certainly the Eastern philosophies or mind-studies have angles (curves?) that the West neglects. And Eric, I don’t think psychedelic phenomenological information is to be entirely neglected. Back in 1970, on the one really serious trip I took, I noticed that I had (unwittingly) “bracketed” my ability to correct for distortion and irregular coloration, and my visual inputs/phenomena were in completely raw form, with wide-angle lens distortion and super-spotty skin. Husserl talks, I think, about peeling off layers of phenomena to get closer and closer to the raw core…though, on the other hand, what’s so great about raw? Bracket that Puritan quest, dude, and enjoy the pretty music and the luscious colors and gorgeous shapes.

March 18th, 2017 at 1:33 pm

Hi Rudy: I reference your mention of Gödel discussing how time-travel is possible since to time travel you can’t have any personal desires. This is actually true as I discovered by doing intensive qigong training to finish my master’s degree in 2000. Also I discovered that ghosts and spirits are indeed real. Science is starting to confirm these “dimensions” via biophotons and quantum coherence. So when “light is heavy” as relativized mass by “turning the light around” in meditation, then we get quantum relative entropy as the spin angular momentum of light, creating momentum energy – the source of qi or prana enabling precognition, levitation, etc.

Also check our Gerard ‘t Hooft’s latest essay notes on how we exist in virtual quantum black holes arising from “timelike moebius strips.” This is the “noncommutative phase space” that creates entanglement – as the fifth dimension, as astrophysicist Paul S. Wesson detailed. Wesson said it explains spiritual phenomenon. I have the research details on my blog.

March 21st, 2017 at 5:21 pm

Wonderful post. I don’t know why I have not visited lately. Wasting too much time on FB I suppose.