[Additional note, made in December, 2014. I did finish my novel about Turing. It’s called Turing & Burroughs, and you can read it in paperback, ebook, or a free CC edition.]

I have an extra-long entry today, mainly describing the computer pioneer, Alan Turing. Note that his hundredth birthday would be June 23, 2012! Happy birthday, Alan.

As I mentioned in an earlier post, I’m starting to write a novel about Alan Turing with the working title, Turing & Burroughs. I started with three stories and now I’m building a novel-length story arc. You can read the three stories online. #1 “The Imitation Game” as a PDF, #2 “The Skug” in the Flurb webzine, and #3 “Tangier Routines” in Flurb as well.

The book will involve time-travel, and some slug-like beings whom I call skugs. They’re from Skugland, which will, I believe, turn out to be Earth’s far future. At one point Turing will be living near me in the nearby village of Los Perros, and I will meet either him or someone who knows him.

Today I started on a painting with working title, “Turing and the Skug,” which shows Alan standing outside the local Los Perros Ace Rural Supply Hardware on Santa Cruz Avenue. Here’s a mockup that I collaged together for the design. I see Alan on foot, his future lover Rodrigo on the forklift (played by Javier Bardem in this mockup), and a rather large skug creeping out of the supply barn.

I’m leaning towards a three-act structure for the novel, the old Monomyth pattern: Departure, Initiation, Return. Someone finds about some weird aspect of the world, then travels to the odd place and has amazing experiences, and then brings the lessons and the elixir back home.

Even more concisely, I might call the pattern zzt-shine-zzt, where the first zzt suggests a rolling forward to encounter something, the shine is the encounter, and the second zzt is the rolling back. In the early 1980s I was using that phrase with my kids to describe the motions of the groundhog in Punxsutawney Phil, in Pennsylvania, who supposedly comes out of his hole on February 2, and, if he sees his shadow, retreats, thereby predicting six more weeks of winter. I was bitter because the predictions seemed nearly always to be for more winter, and I felt this was a hoax perpetrated upon us by evil forces who wanted us to believe it would be winter, knowing that the back-reaction of society’s massed mentation upon mutable reality would in fact make the prophecy come true. I argued that Punxsutawney Phil was in fact a robot, a stuffed groundhog on wheels on rails, rather than being a live animal, and that the reality-manipulating authorities, simply rolled him out, flashed a light, and rolled him back. Zzt-shine-zzt! The kids loved this rant, they were amused by how passionate and bitter I would get.

By way of creating my Alan Turing character, I’ve been studying Andrew Hodges, Alan Turing: The Enigma, a 500+ page biography, first published in 1983. The edition I have is the Walker and Company paperback of 2000. This summer I finally read the whole book through, marking passages that seemed potentially useful for my novel. I’m in the process of copying out some of the most useful bits, indicating the year, and Turing’s approximate age (he was born on June 23, 1912.) I love what an odd-ball rebellious proto-hacker Alan was.

1935, age 23. If they [undergraduates] came to his rooms hoping for a glimpse of King’s [college] eccentricity, they were sometimes rewarded, as when Alan say Porgy the teddy bear by the fire, in front of a book supported by a ruler, and greeted them with “Porgy is very studious the morning.”

1939, age 27. “…his room…was liable to be found with a sort of jigsaw puzzle of gear wheels across the floor…It was certainly far from obvious that the motion of these wheels would say anything about the regularity with which the prime numbers thinned out, in their billions of billions out to infinity. Alan made a start on doing the actual gear-cutting…”

1940, age 28. “[Worried about an invasion] He bought two [silver] bars worth about £250, and wheeled them out in an old pram to some woods…. One was buried under the forest floor, the other under a bridge in the bed of the stream. He wrote out instructions for the recovery of the buried treasure and enciphered them. … The clues were stuck in an old benzedrine inhaler and left under another bridge.” [And later he could never find the ingots.]

1941, age 29. “Trousers held up by string, pyjama jacket under his sports coat… There was his voice, liable to stall in mid-sentence with a tense, high-pitched ‘Ah-ah-ah-ah-ah’ while he fished, his brain almost visibly laboring away, for the right expression, meanwhile preventing interruption. The word, when it came, might be an unexpected one, a homely analogy, slang expression, pun or wild scheme or rude suggestions accompanied with his machine-like laugh; bold but not with … coarseness …but with the sharpness of one seeing it through strangely fresh eyes.”

1942, age 30. Turing joined the Home Guard so he could learn to shoot. “[Turing] had to complete a form, and one of the questions on this form was: ‘Do you understand that by enrolling in the Home Guard you place yourself liable to military law?’ Well, Turing, absolutely characteristically, said: There can be no conceivable advantage in answering this question ‘Yes’ and therefore he answered it ‘No.’ … And … he was duly enrolled, because people only look to see that these things are signed at the bottom.” He learned to shoot, but he refused to attend parades, and the apoplectic chief officer confronted him, and Turing said, “You know, I rather thought this sort of situation could arise…If you look at my form you will see that I protected myself against this situation.” He’d decided on the “optimal strategy if you had to complete a form of this kind. So much like the man all the way through.”

[Scott Kildall and Victoria Scott, working on their project “Gift Horse” for the San Jose 01SJ art festival]

1943, age 31. He liked Greenwich village. “He said, ‘I’ve spent a considerable portion of time in your subway. I met someone who lived in your Brooklyn who wanted me to play Go. … I had a dream last night. I dreamt I was talking up your Broadway carrying a flag, a Confederate flag. One of your bobbies came up to me and said: See here! You can’t do that! And I said Why not? I fought in the War Between the States.’ Alan’s curious English voice, like [a] system encoding information via frequency rather than by amplitude, made a vivid impression on his … colleagues.”

1943, age 31. “His high-pitched voice … stood out above the general murmur of well-behaved junior executives … Then he was suddenly hear to say: ‘No, I’m not interested in developing a powerful brain. All I’m after is just a mediocre brain, something like the President of the American Telephone and Telegraph Company.”

1943, age 31. Riding the ship from New York back to England, “…he spent his time studying a twenty-five-cent handbook on electronics, the RCA Radio Tube Manual, and invented a new way of enciphering speech.”

1943, age 31. “Alan was particularly good at taking some quite elementary problem and showing how some point of principle lay behind it¬—or conversely, illustrating some mathematical argument with an everyday application…It might be [for instance] wallpaper patterns for an argument about symmetries. His ‘paper tape’ in his [seminal monograph on]Computable Numbers, had the same flavor, bringing an abstruse branch of logic down to earth with a bump.”

1944, age 32. “With holes in his sports jacket, shiny grey flannel trousers held up with an ancient tie, and hair sticking out at the back, he became the cartoonist’s ‘boffin’—an impression accentuated by his manner of practical work, in which he would grunt and swear as solder failed to stick, scratch his head and make a strange squelching noise as he thought to himself, and yelp when shocked by the current that he forgot to turn off before soldering the joints in his ‘birds nest’… of electronic valves.”

1945, age 33. Working on a system named Delilah, for encrypting audio transmissions of speech, he developed what we would now call a chaotic but deterministic multivibrator circuit for generating reproducible noise patterns for encrypting the sounds. “He hated the showmanship that was required in negotiating for equipment. It was forever his bitter complaint that more adept players—‘Charlatans,’ ‘Politicians,’ ‘Salesmen’—would get their way not through expertise but through clever talk.” When “the Delilah actually worked—that was the joy of it, for all its deficiencies. Alan had created a sophisticated piece of electronic technology out of nothing, and it worked. … Alan’s braces [suspenders] burst. Harold Robin, the chief engineer of the organization, produced some bright red cord from an American packing case. Alan used it every day thereafter as his normal way of keeping his trousers up.”

1945, age 33. “The world had learned to think big, and so had he …[ now] he wanted ‘to build a brain.’” 1947, age 35. “His whole enterprise was motivated by a fascination with …an understanding of the magic of the human mind. … ‘In working on the ACE [computer] I am more interested in the possibility of producing models of the action of the brain than in the practical applications of computing.’”

1946, age 34. “[a colleague] found many days when it was better to keep out of the way of the now somewhat isolated ‘creative anarchy’ that was Alan Turing. ‘Likeable, almost lovable … but some days depressed,’ he appeared; his mercurial temperament and his emotional attitude to his work showing clearly.”

[One of my best SJSU CS students ever, John Briere, now a manager at Adobe, posed with an SJ01 exhibit that consists of wrecked cars aimed at a drive-in movie screen.]

1947, age 35. “His whole enterprise was motivated by a fascination with …an understanding of the magic of the human mind. … ‘In working on the ACE [computer] I am more interested in the possibility of producing models of the action of the brain than in the practical applications of computing.’”

1948, age 36. “Alan had told [his mathematician friend and confidant] Robin [Gandy] that, ‘Sometimes you’re sitting talking to someone and you know that in three quarters of an hour you will either be having a marvelous night or you will be kicked out of the room.’ … To the fastidious [Alan’s] open-necked, shabby, breathless immediacy came as messy and coarse, though there were redeeming features; he could put on a roguish charm…and besides his piercing blue eyes he had thick, luxuriant eyelashes and a soft-contoured nose. … Sometimes he struck lucky.”

1948, age 36. Alan attended a talk by Wilkes, who was designing a rival computing system: “Afterwards he meanly said, ‘I couldn’t listen to a word he said. I was just thinking, how exactly like a beetle he looked.’”

[Blower unit for an SJ01 “air robot” which will have many wobbly inflated tubes.]

1948, age 36. “He was … fascinated by the fact that a machine … could be perfectly deterministic at on level, while producing something apparently ‘random’ at another. It gave him a model for reconciling determination and free-will.”

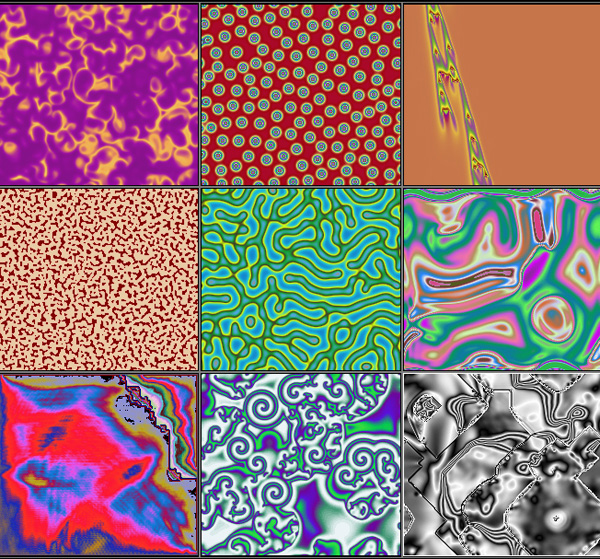

1950, age 38. Alan had bought a house in Wilmslow near Manchester by now. He was turning away from computers. He was working towards a paper on morphogenesis, or the study of how plants and embryos grow. “…somehow brains came into being every day…how did anything know how to grow?…Alan … thought about embryology all the time…The greatest puzzle was … how biological matter could assemble itself into patterns… [that were] enormous compared to the size of the cells.”

1950, age 38. Biologist J. Z. Young recalled his conversations with Alan. “…there was his rather frightening attention to everything one said. He would puzzle out its implications often for many hours or days afterwards. It made me wander whether one was right to tell him anything at all because he took it all so seriously.”

[Image of a computed animal-coat pattern, taken from Turing’s last published paper, “The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis,” which he wrote in 1951. This link works today, but it can be hard to access a full pdf file of this important paper. If all else fails, you can read the pages one by one as photoimages in the Turing archive.]

1951, age 39. One of Alan’s colleagues, Jefferson, described Alan as “‘a sort of scientific Shelley,’ … Shelly also lived in a mess, ‘chaos on chaos heaped of chemical apparatus, books, electrical machines, unfinished manuscripts, and furniture worn into holes by acids,’ and Shelley’s voice too was ‘excruciating; it was intolerably shrill, harsh, and discordant.’” Alan had a “wince-inducing, mechanized laugh.” Alan spoke of his work on mathematical simulations of pattern formation on animals as “waves on cows and waves on leopards.”

[Ken Gregory and a colleague working on a giant aeolian harp for 01SJ]

1951, age 39. Alan’s rooms had, “the great muddle of pots and pans full of weeds and smelly mixtures, in which Alan was pursuing his desert island hobby, seeing what chemicals he could make out of natural materials, and in particular doing some electrolytic experiments.” He was running computer simulations of his differential equations, calculations that ran overnight, and “…usually he could be expected to emerge in the morning waving around print-outs to anyone who was around—‘giraffe spots,’ ‘pineapples’ or whatever—and then go back to sleep until the afternoon.”

1952, age 40. Alan was charged with Gross Indecency after telling the police he’d had sexual encounters with a young man he’d met in the street. Alan had gone to the police as one of the young man’s friends had subsequently robbed Alan’s house. Alan was not overly concerned about being exposed as homosexual. “…he did not wish to be accepted or respected as the person he was not. He was likely to drop a remark about an attractive young man, or something of the kind, on a third or fourth meeting with a generally friendly colleague. To be close to him, it was essential to accept him as a homosexual; it was one of the stringent conditions he imposed.”

1952, age 40. Alan’s brother advised Alan to plead guilty, given that he’d already made a self-incriminating statement to the police. “He though Alan had been a ‘silly ass’ to go to the police about the burglary, and that everything he had done showed his naiveté about the world outside the intellectual elite.” Among his colleagues, “There was no question of helping or extending sympathy to him—his personality ruled it out. … he bore his afflictions cheerfully.”

1952, age 40. So Alan pleads guilty, and they give him a year’s probation plus some crackpot “organo-therapy,” which involved injecting him with estrogens (intended to reduce his libido but now, oddly, a therapy often used by men planning a sex-change). In a letter after the trial, Alan writes, “The day of the trail was by no means disagreeable. Whilst in custody with the other criminals I had a very agreeable sense of irresponsibility, rather like being back at school. The warders were rather like prefects. I was also quite glad to see my accomplice again, though I didn’t trust him an inch.”

1952, age 40. “A further consequence which for another person might have been major, but which for Alan had little significance, was that, with a criminal record of ‘moral turpitude,’ he was henceforth automatically barred from the United States.”

1952, age 40. “…if his computer days were over, this did not mean the end of his underlying interest in the human mind.” He began seeing a Jungian psychoanalyst, hoping to integrate thinking and feeling and, “to apply intelligence to himself; to look at his own system for the outside like Gödel [in his incompleteness theorem], and break his own code…”

1953, age 41. Working with his therapist, Alan wrote an unfinished science fictional story about a gay scientist who’s known for some aerospace device known as Pryce’s Buoy [cf. the Turing Machine]. “He would walk round the shops…until he saw something which took his fancy, and then think of some one of his friends…who would e pleased by it. It was a sort of allegory of his method of work (though he didn’t know it0 which depended on waiting for inspiration.” See the these pages in the Turing Archive; note that to access these pages you have to click through a screen accepting the terms of use. Here’s another quote I found there: “Alec had been working rather hard two or three weeks before. It was about interplanetary travel. Alec had always been rather keen on such crackpot problems, but although he rather liked to let himself go rather wildly by appearing on the Third Programme when he got the chance, when he wrote for technically trained readers his work was quite sound, or had been when he was younger. This latest paper was real good stuff, better than he’d done since his mid twenties when he had introduced the idea which is now commonly know as ‘Pryce’s buoy.’ He always felt a glow of pride when the phrase was said.”

[That sinister Trojan virus horse.]

1953, age 41. In a letter to his friend Robin, “I’ve got a shocking tendency at present to fritter my time away in anything but what I ought to be doing. One thing I’ve done is to rig the room next [to the] bathroom up as electrical lab.” He called his lab the “nightmare room.” “In this ‘laboratory’ he was able to do ‘desert island’ experiments of an electrolytic kind… He would use coke [or coal] as electrodes … and weed juice as a source of oxygen . He liked to see how many chemicals he could produce, starting from common substances like salt. Later, to pass an afternoon with a friend, he’d try to concoct a non-poisonous weed killer and sink cleaner from natural ingredients.

1953, age 41. In his letter to Robin Alan also said “Went down to Sherborne [his old boarding school] to lecture to some boys on computers. Really quite a treat in many ways. They were so luscious, and so well mannered, with a little dash of pertness, and Sherborne itself quite unspoilt.”

[Stargate at Lexington Reservoir.]

1954, age 41. “The waves of inspiration had come only once every five years… the Turing machine in 1935, naval Enigma in 1940 [cracking the Germans’ code], the ACE [computer design] in 1945, the morphogenetic principle in 1950.” In 1954, he was working on another morphogenesis paper, on the so-called “word problem” of mathematical logic, and some physically applicable mathematics called the “spinor calculus.”

1954, age 41. On a seaside excursion with his therapist’s family, Alan visited “the Gypsy Queen, the fortune-teller….When he came out, he was white as a sheet, and would not speak another word as they went back to Manchester on the bus.” On June 7, 1954, just short of his 42nd birthday, Turing killed himself—or was assassinated by the British secret police group, MI5.

Postmortem. “In Alan Turing’s case the questions [about his death] were not obvious, but precisely because the field of his expertise [code-breaking] was even more closely guarded than that of nuclear weapons.” Turing’s “iconoclastic originality had been acceptable in the brief period of creative anarchy…required to solve the unsolvable Enigma [code]. But by 1954 a very different mentality prevailed.” Speaking of some of his papers left at home, Alan told his mother “the document is ‘unclassified’ (an idiotic word of American origin meaning ‘not in the least secret…)” “Turing never truly belonged to the confines of the academic world. His scattered efforts to appear at home in the upper-middle class circles to which he had been born stand out as particularly unsuccessful….” He had a “disdain for the more trivial functions of academic life” and a “mixture of pride and negligence with which he regarded his own achievements.”

[Some Turing-style patterns computed by my continuous-valued cellular automata package CAPOW]

Alan reminds me of some of the mathematicians and computer scientists that I’ve known. For mathematicians, the switch into CS is a kind of liberation, as then we get to make things. And Turing was already moving past the rigid computing machines and into biotech. I think Turing would have loved the 01 festival, he might have built something amazingly weird. Maybe a skug!

September 11th, 2010 at 12:24 am

I’m also currently reading Hodges’ excellent (but long) biography which I cannot recommend enough. Am only up to 1947 so still have a long way to go. I found it to be fascinating and well worth engaging in the more challenging sections on mathematics and philosophy.

I don’t know if you’ve already seen Hodges’ Turing website which is also excellent and the Turing Digital Archive where you can read Turing’s words and get a grasp of just how messy he worked on paper. (And handwriting analysts would love it.)

September 11th, 2010 at 12:25 am

doh, yes I see you linked to it in the last para.

September 11th, 2010 at 5:33 am

The juxtaposition of 01 images with this story is inspired. I am now in a state of acute thanksgiving at the vastly greater tolerance for creativity and individuality available here and now. Long may it last, far may it spread. Here’s to flamboyant lesbian hackers in Riyadh!

September 11th, 2010 at 10:29 am

Nice. I will be excited to read the novel.

September 11th, 2010 at 6:32 pm

there is also some book out on alan turing as a connectivist. maybe worth a read in these our connected times.

September 13th, 2010 at 11:29 am

Sherborne – where Turing went to school – is about 5 or 6 miles from where I live, over the Dorset border. It’s a very small town, but very snooty – full of private boarding schools where those not quite wealthy or connected enough to outsource their kids to Eton, etc dump their children. My late father was the ‘Transport Manager’ at the main school in the 80’s, which basically consisted of keeping the school-bus running and fixing the lawn-mowers 😉 It cost more to send a child to that school per year than my dad’s salary.

September 13th, 2010 at 7:26 pm

such a rich base for your pen and wit to have many a fine day. I find myself wanting to suggest plot points and delicious twists, but I’m sure your’s will be ever so much more lovely. looking forward to it.

September 24th, 2010 at 3:52 am

Beyond coincidence the American computor company Apple call themselves Apple and have an apple with a bite as a logo. They should acknowledge their logo as a tribute to the father of computer science.

Never underestimate us Brits.

October 1st, 2010 at 4:25 pm

As a runner I was surprised to recently discover that Alan Turing was a world class runner.

http://www.turing.org.uk/turing/scrapbook/run.html

It’s funny that so little is mentioned about this, especially since running must have been a huge part of his life. It takes quite a bit of training to run a marathon in 2:46:xx (which was 11 minutes slower than the world record at the time) and this was before GPS watches, heart rate monitoring, books about marathon training, etc. This was not the result of a casual hobby! People who run at that level pretty much plan their lives around it.

October 4th, 2010 at 5:35 pm

Thanks, Efrem, for that link. I’d seen that photo of Turing (cropped down to just show him), but didn’t know where it came from.

The biographies I’ve read don’t go into his running very deeply, perhaps because the authors weren’t runners. But certainly it was a big part of his life, and I’m glad you reminded me of this, I’ll work that into my novel.

November 22nd, 2010 at 11:26 am

I like the note about Greenwich Village (which might confirm my Castro hypothesis). I too liked reading Hodges’ book and web site, but I never made my first trip to the UK until 2000 (and even back in 2001), and it didn’t occur to me to contact and look up Dr. Hodges back then. I did pass thru once in between then and now and met with Museum officials briefly, but no time for Hodges.

I appreciate the comments about academia, but I think he just needed the right department. It was his time. I’m not clear that he would have taken to bio tech or other ideas which makes all this speculation more the shame for his untimely demise as the Brits would say. I would still really want to know what Turing was like for myself. I’m amazed that for 6 decades of academic talent in the field following him, that some of his ideas have no been overturned, changed, or modified as many academics do.

February 7th, 2013 at 11:24 am

I’m only 13 and at school I am learning about the Enigma in which my dad briefly mentioned to me before. For my project about all of this, one task was to design a monument and label it with why he’d look that way and I would just like to say thank you because this really helped me to see what Alan Turing was really like. This was very helpful to me 🙂

February 7th, 2013 at 11:25 am

I live in England by the way, so this info was really helpful !

February 7th, 2013 at 1:17 pm

Glad this post was useful to you, Julie. I might also mention my recent novel TURING & BURROUGHS which dramatizes what might have happened if Turing had avoided his death, had an affair with the Beat author William Burroughs, and traveled to the U.S. The novel grew out of the research summarized in this blog post. The novel does have a certain amount of sex in it, so I wouldn’t feel quite comfortable in whole-heartedly recommending it to a 13 year old girl, but you might keep it in mind, if not for now, then for later. You can take a peek at the book online and decide for yourself. See the book’s website: http://www.rudyrucker.com/turingandburroughs/