Transreal Books, For sale everywhare!.Read it, and understand our now.

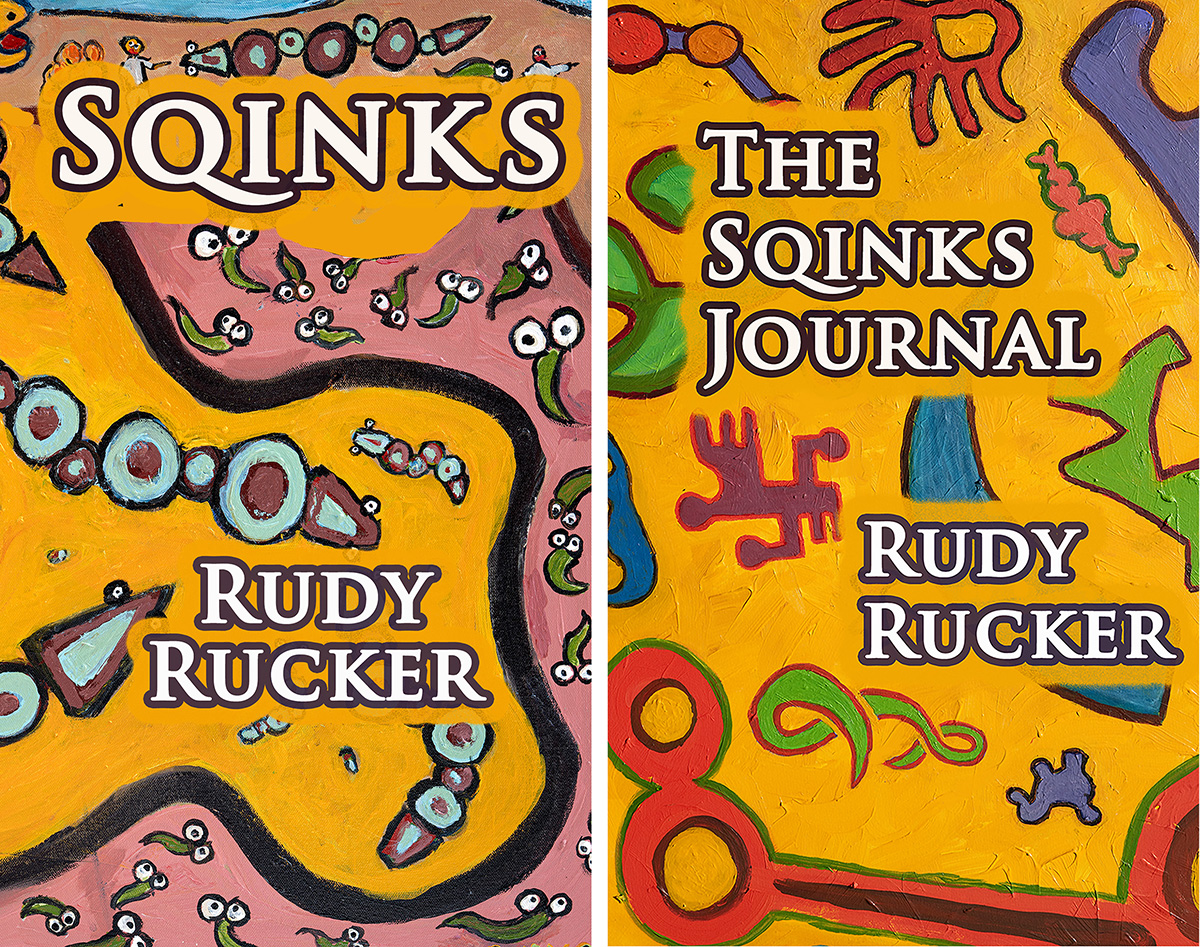

Sqinks. 265 pages.

Hardback: $24.95 ISBN: 978-1-940948-65-2

Paperback: $14.95. ISBN: 978-1-940948-59-1

Ebook: $8.95 ISBN: 978-1-940948-60-7

Amazon and Other sites

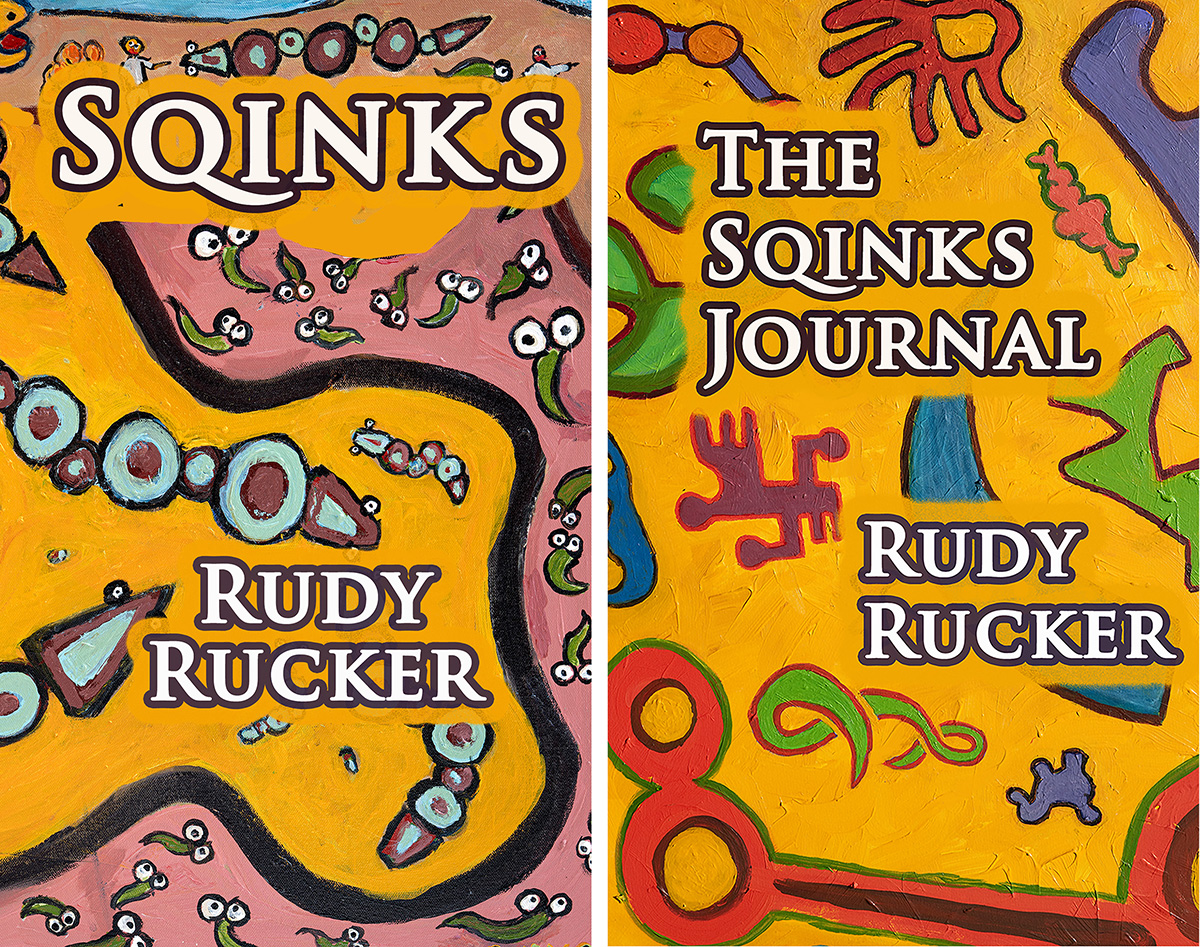

The Sqinks Jounral. 291 pages.

Hardback collectors edition: $120 ISBN: 978-1-940948-64-5

Paperback: $35 ISBN: 978-1-940948-61-4

Ebook: $8.95 ISBN: 978-1-940948-63-8

Amazon and Other sites

Twp books. A novel, Sqinks. And The Sqinks Journal, a book-length a volume of writng notes,

Sqinks is a visionary tale of odd aliens with strange plans. A vintage Rudy Rucker rollercoaster: fresh ideas, big laughs, and high emotions. A novel about our new AI, with a touch of satire. Set in San Francisco. Told by an old writer---who is in fact writing Sqinks as we go along. He's lonely, he meets a woman. A transreal cyberpunk love story!

The Sqinks Journal is an author’s journey. Rucker’s notes on losing his wife, living inside his SF novel Sqinks, and and finding love once more. Sad and happy. With a master’s insights into the writer’s craft, and a cyberpunk’s take on the new AI. Witty and profound. Only thirty copies of the hardback collecters editon will be printed.

Sqinks is a visionary tale of aliens in today's San Francisco. The sqinks. In some ways they're like our new AIs. But in other ways, they're a thing nobody's ever seen. Nobody except Rudy. And, um, these aliens seem to have an interest in replacing human brains. It's a surreal rollercoaster, rich with ideas, scares, and laughs.

The narrator is, in a way, Rudy himself. The character is a seasoned SF author who's also writing a novel about the odd world he's in. A touch of what Rudy calls transrealism. Yes, it's science-fiction, but, yes, it's about our real world.

Rudy being who he is, the novel is cybperpunk---2020s style, faster and funnier than before. New mind tech, and new struggles for human freedom.

And it's a love story. A transreal cyberpunk love story. It'll make you laugh, and it'll make you feel good.

The Sqinks Journal is an author’s journey, a master's struggle with their craft.

It begins with the death of Rudy's wife. After a year of heavy grief, he begins writing again: a visionary and unshackled novel, born from the dailyness of life itself.

A woman appears---a human character from the cosmic novel, the same as Rudy. A gift from the muse..

The journey is a struggle and a dance---incomprehensible and meaningful. With steady comfort from the writing itself. And rich with a master’s insights into technique and process.

Rudy Rucker is a writer and a mathematician who worked for twenty years as a Silicon Valley computer science professor. Rucker is regarded as contemporary master of science-fiction, and received the Philip K. Dick awards for his cyberpunk novels Software and Wetware.

It’s worth noting that his novel Software (2020), was the very first SF work to introduce the by-now-very-familiar notion of transferring a human personality to a bot. What’s more, Software was the first SF novel in which robot minds are evolved, rather than being designed.

As well as writing cyberpunk, Rucker writes SF in a realistic style known as transrealism—where the author uses SF archetypes to symbolize the concerns of the characters. This is an increasingly common style among mainstream authors.

Rucker’s forty published books include non-fiction books on the fourth dimension, infinity, and the meaning of computation.

See Wikipedia for more.

I funded this Transreal Books publication with a Kickstarter campaign. Many thanks to my backers. I list them below, sorted by the alphabetical order of the first letters of their chosen screen names.

Adam Browne, Abolish ICE, AgentKaz, Alan Borecky, Alan Swithenbank, Alex, Alexander the Drake, Alex McLaren, Alice Steinke, Amy Purvis, Ana Trask, Andrew E. Love, Jr., Andrew Hatchell, Andy J Ward, Andy Ramsay, Angus P. MacDonald, Arthur Murphy, Benet Devereux, BHHenry, Bill Messick, Blechpirat, Bob Schoenholtz, Bruce Evans, Bruce Yarnall, Bruno Boutot, Cameron Cooper, Caroline Couture, Chaostrophy, Chris Horton, Chris McLaren, Chris Mihal, Cindy, Cliff Winnig, Coco Conn, Cory Doctorow, Crazy Eddie, Curtis Frye, Dan Botsford, Dan Cohen, Daniel Aneiros, Danny Joe, Daryl Davis, Dave “Ratfactor” Gauer, Dave Bouvier, Dave C., Dave Dyer, Dave Holets, David Brower, David Good, David Kirkpatrick, David Rains, David Simmonds, Dean Wesley Smith, demian parker, Dennis DementX, Lee Poague, Derek Andersen, Derek Bosch, derekticon, DG Zog, Digital Mark Hughes, Doug Bissell, Doug Diego, Dr. S.O. Teric, Dwayne Plain, Ed deJager, Eddie Churchill, Edward Marr, Eileen Gunn, Embry Rucker III & Tee Bree, Emilia M. Pulliainen, Emleeb, Eric Farmer, Erik Saynisch, Erik Sowa, floss.socialist, Frank Chillamos, full name, fyrfaras, Gary Bunker, George Bendo & Hedvig Bartha, George Van Wagner, GF, graphixTV, Grayson Osborne, Greg Kerkman, GVDub, Harald Niesche, Heath Row, Hellapriller, hemisphire, Herr Doktor Professor Deth Vegetable, Ian “FalsePositives” Irving, Ian Chung, Jaap van, jakob frank, Jason ‘XenoPhage’ Frisvold, Jeffrey K Hallock, Jeffrey Thomas Palmer, Jim Anderson, Jim Gotaas, Jim Guild, Joe D’Agnese, John C Monroe, John Curtin, John P. Sullins, John Tinmouth, Jon McKeown, Jose Brox, Josh Collins, Joshua A. C. Newman, Julia Grillmayr, K. Seifried, K.G. Anderson, Karl W. Reinsch, Karl-Arthur Arlamovsky, Kave, Ken Rokos, KeNTKB, Kernelcoremode, Kevin J. “Womzilla” Maroney, Larry Dickman, Leah A. Fenner, Lee Fisher, Leif Lindholm, LilFluff, Lisandro Gaertner, litlfred, lotek, Mackenzie Bechtel-Hall, Madeleine Shepherd, Mahmur Megrim, Marc Goodner, Marian Goldeen, Mark Frauenfelder, Mark Sylor, Martin Olson, Marty Olson, Matthew Cox, Matthew Moran, Maxim Jakubowski, Michael A. Burstein, Michael Adam Becker, Michael O’Shaughnessy, Michael W Lucas, Michael Weiss, Mike Coats, Mike M., Mike Purfield, Mokmeister, Muddy Steve, Murray Marble, Ned Snow, Nicholas Marritz, Niko Alm, None, Norbert Bruckner, Pat Cadigan, Patrick Edmondson, Paul Goracke, Paul Leonard, PhilA, Philip Procyk, Phillip Vuchetich, R. Eggleton, Ray Cornwall, rdi, Richard Matthias, Richard S, Rick Crain, Rick Ohnemus, Rik Skibinski, rob alley, Richard Lesh, Robert D. Stewart, Rod Bartlett, R.U. Sirius, sabrinaweb71, Saftor, Sajorlime, SCIJMW, Scott “marsroverdriver” Maxwell, Scott Call, Scott Lazerus, Scott Lenihan, Sigsegv, simon travis, Snik, Steve Flores, Steve Gurr, Steven A. Thompson, Takuya Mizuguchi, Tao Neuendorffer, The High Frontier, Tonnvane Wiswell, Thijsc, Thomas Bøvith, Tim + Norma Thomson, Tim Conkling, Tim Messler, Timothy Lee Russell, Timothy M. Maroney, Tj, Todd Fincannon, Tom Foster, Val Delane, Vernon White, Walter J. Montie, William Dass, William TB Fee, Zach Peters, and Your Name Here.

I am profoundly grateful to all the readers who have kept my career alive for, lo, these many years. You’re wonderful.