One Hundred Years

by Mac Tonnies

Today I saw a dead woman in the street, skin drawn around her bones like cheap artificial leather. Her clothes had been peeled away, as they might ignite. As I sidestepped her wrinkled form, I noted that her short blond hair had begun to smolder.

One hundred years was what they had told us sixty years ago. Now, there is no “they,” only a vestigial core of authority held immobile in the growing heat. In forty years, almost precisely one hundred years since my birth, the sun will have eclipsed the orbit of Mercury, a victim of the mysterious celestial tumescence astronomers had observed in other solar systems.

It was a horrific prospect, easily dealt with in the arena of speculation. Remarkably little changed immediately.

One hundred years was a long time.

I’ve never married. Gaile, the woman closest to me, had left me for the subterranean chic of Mars thirty years ago. We had exchanged mail for a while: tellingly formal hypertext updates which we examined with the patience of historians unearthing ancient and unsuspected texts. Then the mail had ceased altogether and I had felt my estrangement manifest as a chill in my bones. Something terminal and sad had crossed the gulf of interplanetary space, borne on wings of thought.

It’s cooler on the surface of Mars and cooler still on the Jovian moons, which have enjoyed an exponentiating population as the ice melts, turning Europa and Ganymede into surreal paradises. In time, they will be absorbed as well, wrapped in a tissue of solar cancer.

On Titan, the cold, murky moon of Saturn—the only world in the solar system other than Earth with extant native life—the last of our ships are being built, hammered together out of ice and metal from Saturn’s rings.

Each ship—there are four now—can contain no more than four-hundred colonists: willing relics of a doomed race. They will be our first emissaries to the stars, assuming they survive the voyage. The technology behind the ships is largely untested, the life-support dubious. But it was all we were capable of, faced with our belated warning.

I secretly hope they perish.

I had applied for the evacuation, of course. I suspect Gaile did too. I can imagine her ascending to the surface of her cool red world, the constellations strewn in welcome. Maybe she even made the cut; she was a better person than I—robust, vital, her inhibitions held in enviable check.

The Consortium had rejected me within seconds of my application. I burned my computer the evening I received the rejection, delighted at the snapping sounds of the brittle, flaming silicon. The screen, still glowing with Consortium animations, withered like a leaf.

People have taken to ritualistic self-sacrifice. Last week over a thousand people boarded a grounded jumbo jet riddled with explosives and vats of slow-burning chemicals. Their demise was a cough of oily smoke on the horizon that lingered for days, throwing a dark overcast over my building. Sight-seers thronged the street below my apartment window, decked out in electrical coolsuits.

The smoke from the burning jet finally dissipated and the street cleared. Rumors of similar sacrifices saturated the Net: hangars flooded with gasoline set on fire by the simultaneous dropping of a thousand cigarette lighters, swimming pools waist-deep with ethanol blooming into sarcophagi.

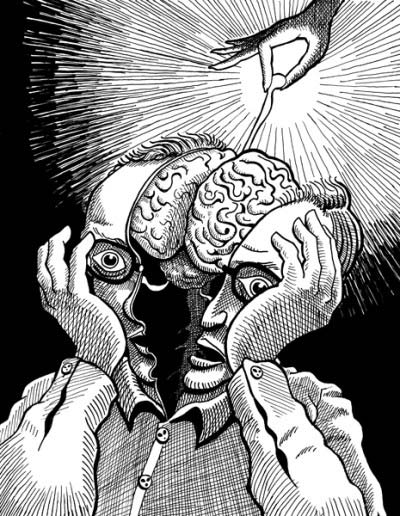

I entrusted my brain to a well-dressed young man with vague medical credentials. His offices had grown like a posh cancer, taking over the bottom four floors of a downtown clave. I could almost hear the autumnal sigh of liquid nitrogen behind the sculpted steel walls.

The scanning procedure was brief, carried out by an emaciated-looking humanoid robot with luminous gray slits for eyes and deftly swiveling arms. A woman in a turban and sarong watched the proceedings from across the room, statuesque atop her black platform sandals. She read aloud from text displays painted onto her arms, lulling me into a trance that made the robot’s sharp fingers in my hair seem almost distant. We had swapped pleasantries in the foyer; her name was Sterope.

The clinic went to astronomical heights to appear informal, including designer pheromones circulated in the air. I felt them dig into me, leaving delicious afterimages swimming in my head.

Sterope seemed content with her duties, looking up from the text on her skin to appraise me with the surgically elongated eyes so popular in recent months. Her contact lenses were delicately mirrored and her lips, athletic beneath a lacquer of gloss, creased in an enigmatic smile so perfect I thought it was a side-effect of the pheromone.

When she finished reading—a delightfully eclectic mix of early 21st century existentialist manifestos juxtaposed with choice science fiction—the robot handed me the circular chip that contained my psychoscape: memories, fears, and all the attendant entanglements rendered into a gunmetal token that could easily slip through a sewer grating or a crack between sofa cushions.

Sterope’s warm brown hands enfolded mine as I sat considering myself, turning the download over again and again in my palm as if expecting to summon a doppelganger genie. The woman’s fingers tightened meaningfully on my own. Her eyes were discerning, liquid, at odds with her cheeks and forehead and the laminated arch of her black hair.

I imagined my own distressed body summoned from its chip-bound dormancy. The image was hard to shake: pasty, chemically treated skin like an ectoplasmic shroud, my eyes sunken and desperate under the homey lamplight.

Entering the foyer earlier that day, I had felt some small bit of myself fall away. Did the download capture this bit? Somehow my abrupt union (as I thought of it) with Sterope dispelled the need to ask questions. Answers would come later, or not at all, of their own apocalyptic accord.

I talk with the apartment supervisor as he ghosts through my quarters, checking the chromed walls for lapses in integrity. Occasionally, he’ll caulk an invisible seam with blue gel that fills the room with the smell of rusting metal. I desert the apartment, still linked to my virtuality rig while he unapologetically twists the cap back on, wiping his fingers clean on his beard. Bots accompany him across the room, eyeing my bookshelves like drugged predators. I watch them gazing out my window with a wounded, knowing aspect I cannot begin to emulate or understand.

The sun doesn’t scare them, as it does me, no matter how deeply I think I grasp the cruel equation of my own mortality. I’ll die anyway, regardless of the sun’s inflation. I wouldn’t necessarily have to—a month’s nanotherapy would add another century or so to my lifespan. I could migrate outward like Gaile, waiting to make some future cut as the sun swallows the inner planets.

But for some reason I’ve never undergone even basic therapy; I put it off until the sun’s threat provided a twisted validity for my indecision. As if, deep down, I had always known the earth was doomed: a premonition that must have germinated as I sulked in my mother’s artificial womb, sucking distilled life through the gill-slits on my neck.

Sterope and I met at one of the sad downtown cafes with old neural interface rigs gathering dust on the countertop. Geriatric robots served us rice tea and bagels.

Sterope reached into her purse and withdrew a ceramic pendant. Dutifully, I handed her the token of my identity and watched her clasp it shut before handing it back to me with a long-fingered flourish. The palms of her hands rippled with newsfeeds from the research stations on Venus, quietly foretelling our own futures.

I sipped scalding tea and slipped the pendant into my breast pocket. I felt its vague metallic warmth against my chest as I regarded the archaic interface rigs. Gently, I threaded a thoughtwire between our sinus uplinks and listened to the placental jabber of her id. Her thoughts took on the guise of images: transient, half-formed, evocative. I felt I could drown in them.

Dimly, I watched her unzip a flask of image-conductive lotion and spread it on my hands and wrists. We watched our thoughts coalesce, warped to the contours of bone and muscle: a pornography of mentation.

If we concentrated on not concentrating, the images would almost begin to make sense. We held our breath at the sight of the sun flickering in a chrome sky. Fuzzy, crooked shapes that might have been chromosomes flexed and burned endlessly at its core.

Smoke from some suicidal fire roiled overhead as we caught an armored cab and made for my apartment. Ash peppered the windshield with the calligraphy of the newly dead. Sterope retreated into the accordioned folds of her coolsuit, fingernails visible through the pastel latex gloves. She smeared the windows with image lotion and we jacked in like eager children, the soiled artificial night replaced by a consensual synaptic mutter:

Evacuation ships moving off into deep-space, solar sails wafted by cancer-radiance. Martian polar caps gushing and melting, flooding the empty sea bottoms while Gaile watches over them with Olympian indifference, knowing that the seas will vanish once again, this time not into ice but thick, writhing steam.

The city passed in a procession of foreboding white thermal bunkers and tanks of liquid nitrogen.

We retired to the silent chill of my apartment. The administration had paid a visit during my absence, rubbing crystalline patterns onto the increasingly brittle walls to keep them from shattering from sheer cold. I had left the wall-to-wall counters strewn with personal relics: incomprehensible electronics from the previous century, volumes of fiction committed to scaly yellow paper.

I drew the shades across the refrigerated window as evening fell. The night throngs were already underway. Revelers in coolsuits and mobile air-conditioned tents lined the sidewalks, setting off fireworks in the street. I watched a man happily dousing himself with gasoline, waiting for an errant firecracker to set him alight. A hundred bent voices pressed against the cold glass.

We listened to my collection of late 20th century music, undressing each other to the leaden beat of vintage trip-hop. The glowing fabric of Sterope’s sarong gilded her waist and breasts in bloodred light. The screens on her bare arms flashed erotic poems in forgotten languages. Hieroglyphics morphed into Sanskrit; runes and mandalas blossomed like foliage in an Ernst painting.

Naked, we painted ourselves with the last of her image lotion. We patched into each other, turning our bodies into mirrored Freudian billboards. Dreams swam across her stomach, orbiting her navel like flotsam around a youthful star. Freed of her turban, her hair sprouted shoots of fiber optic and thin motorized braids that wound around my hands and wrists as we watched ourselves reiterated on each other’s flesh:

Gaile’s face, elongated and ashen, staring up into a Martian watercolor sunset / Patterns of cloud as seen from orbit, resolving slowly into superheated hurricanes / Florida beaches hammered by boiling rain, leaving a weave of steamy contrails.

The visions possessed the shrill clarity of a newscast. Our lust was a broadcast, a transmission from a parallel universe.

We coupled gently, basking in each other’s heat. The image lotion, cracked and drying on our skin like mud, exhausted its power and reverted to default, displaying starscapes that mimicked the emptiness of space. It was as if our fingers could pass through one another to caress starlight and grow numb in the vacuum.

Blindly, I reached out to Gaile to say goodbye for the millionth time.

I dreamed my Melting Walls dream, in which buildings collapse slowly in on themselves like molten taffy. Remarkably, there is no heat. A wintry chill passes through the city, scraping against the skyline with a sound like old-fashioned television static.

We awoke to explosions. The window shook. I twitched, lost in some forgettable private hell, and watched black smoke rising from the skyline.

Drugged with fatigue, eyes smarting, I watched Sterope buckle her sandals and finish arranging her hair in the aseptic light of my bathroom. She fussed with her turban and entered the living room, heels sinking into the cold rubber floor. The dormant image-lotion left over from our lovemaking formed a psychotic mural at her feet.

“What are you going to do with it?”

I stood and began dressing, feigning patience. I could feel Sterope’s stare biting through me. “Do with what?”

“Your mind. The one on the chip.”

I smiled dismissively. “I suppose a record needs to be kept,” I said, indicating my collection of cultural detritus. “Or at least I think so. A neurological plague diary, if you will.”

I paused to watch the last of the night’s revelers scramble for cover as the sun rose, momentarily blinding me through the polarized glass. Unattended piles of litter burst into flame on the sidewalks and oozed white smoke.

Sterope’s arms gripped my waist from behind. “Immortality is nothing to feel guilty about . . .”

“Immortality?” I scrutinized the locket she’d given me. “This chip isn’t me. It’s a token. Maybe even a metaphor.” I turned and kissed her neck as sunlight filled the bedroom. “But it’s not me, just a testament to my unflappable ego.”

Sterope pushed me away gently, still smiling. She fished a small, gunmetal disc from a hidden crevasse on her naked thigh. We’d made love all night and I hadn’t even noticed it.

“I’m uploaded, too,” she said. “So I guess your ego-trip argument doesn’t hold.”

I touched the disk timidly and looked into her mirrored eyes, which glowed with implacable mirth.

“There’s something you’re not telling me.”

“The scanning and uploading was only part of the procedure you paid for. You didn’t know?”

“Do you honestly think I’ve checked my credit account? I’ve got forty years left, at best. I’m as good as dead.”

Sterope finished dressing. I indulged myself a last glance at her bare thighs, still mottled with dried image lotion.

“Do you have a car?”

I hesitated. “I can get one.”

Sterope knotted her sarong with deft fingers. “The let’s go. We have an appointment to make.”

The self-driven taxi turned off the main city artery and headed for the desert, tires cracking fused sand as the speedometer raced to 120. We huddled in the liquid nitrogen-cooled cabin, sipping drinks through our coolsuits. The cab wasn’t equipped for prolonged daytime use, and the odds were I wouldn’t get my security deposit back. I couldn’t have possibly cared less.

“I remember the desert from when I was a kid,” I said. “The Earthside SETI project was stationed somewhere out here.”

Sterope nodded inside her flexible helmet. “Some of it still is. The Consortium uses the radio telescopes to track the arks.”

Gaile again. I stared grimly out the window and wondered what Mars was like, if the Sun’s envelope had begun to melt the polar caps and subsurface ice.

“Look,” Sterope said, staring at the windshield. I followed her eyes. On the horizon, the warped tresswork of a radio telescope gleamed like a spider web slashed by an errant footstep.

A blackened infrastructure surrounded us as we drove closer. Thermal bunkers protruded from the ground near the few intact antennae, shrugging off the impossible heat. I noted mammoth stores of liquid helium and networks of throbbing pipes. A few suited figures stalked the landscape like fat, awkward robots from a child’s drawing.

Two of the figures stopped whatever they were doing and dragged a white, wrinkled modular corridor toward our car, which braked and parked neatly between two tree-sized clumps of unfathomable machinery.

“We’re expected,” I said, somehow less than enthusiastic. We listened to muffled snaps from outside as the suits attached the corridor to the car.

“We’re here,” Sterope said. She began unbuckling her coolsuit, tossing the gloves to the upholstered bench seat with a faint grimace of distaste. “We won’t need the suits anymore. Go ahead; take yours off. I can’t even see your face through that damned silver visor.”

I followed Sterope’s example. The cab’s gullwing door folded open as I peeled away my leggings, accidentally tearing some of the cooling ductwork. Freon leaked onto the floor like phosphorescent blood.

The door stopped short where the insulated corridor had been attached. We dashed out of the cab’s back seat and over the doughy foam floor laid out before us, our arms brushing against the sagging, claustrophobic walls. Ahead of me, Sterope wore only her sarong and turban; her bare feet were silent on the cheap modular tile.

Within seconds we reached a refrigerated dome at the opposite end. Blinking, I made out computer flatscreens, a bunk-bed, luminous starcharts.

The entrance hissed shut behind us and we were abruptly alone and vulnerable, somehow more so than we had been in the privacy of my apartment or that first encounter with the virtuality rigs. I heard the chugging of an airlock; I must have missed it in our hurry to escape the tunnel. The door reopened and two men entered, dismantling their coolsuits with practiced, unthinking ease. Both were bald and anemic-looking, with craned necks and furtive unblinking eyes that glinted phosphor-blue in the murky light. Hackers of some sort.

The last man to enter appraised us, eyes lingering on Sterope’s pert breasts. “You’ve come to cash it in,” he said, eyes widening as he spoke. He had the look of someone privy to some arcane secret.

He extended a narrow hand, palm cupped and waiting. I found myself opening my locket and placing the upload chip on the white, expectant flesh. He hefted it as if attempting to divine my worth. I noticed with a start that his palm was lined with tiny translucent cilia that adhered to the edges of the chip like greedy snakes.

“That’s some graft,” Sterope said. I noticed a tone of familiarity in her voice. The man shrugged and clenched his fist over my upload, the corners of his lips twitching as he wrestled with whatever wetware governed the synthesized nerve sprouting from his hand.

He approached a bank of computer drives that glowed green in welcome, rendering him into a wiry silhouette. “We’re sending out four or five people a day now,” he said tonelessly.

The second hacker was huddled over a crystalline mechanism I recognized vaguely as a SQUID detector. Whatever this place was, I thought, it wasn’t cheap. “Four or five people equates to a lot of bandwidth,” he said without looking up. He blinked rapidly as if rousing himself from a dream and addressed Sterope: “You’re going this time, too, huh?”

She nodded.

“Where are they sending us, Sterope?” I asked. I could see constellations from the star charts hugging the curvature of her delicately mirrored eyes, beckoning.

“Not where,” she said, beginning to fuss with the hair behind her ear. She withdrew something narrow and wriggling from inside her skull, the tendons in her neck taut with conviction. “When.”

I awoke inside a new body—undoubtedly mine, but nevertheless new and deliciously raw. The bedside computer handled my questions with a maternal calm. I had been cloned, and my mind downloaded into the new, artificially maturated body. Its contours and quirks were intimately familiar to me, and I took to it as naturally as an embryo to a womb. Nevertheless, I was aware of its newness—the uncorrupted vigor of its vat-grown limbs and unblemished lungs.

My last memory was of submitting to the uploading procedure. After that I encountered only a gap, as if my life was a record that had betrayed its imperfection in a single jarring skip.

I spent a week adapting to my new body under the gentle supervision of a woman named Sterope. Once we went outside for a brief walk through the clinic’s flowered courtyard. The air seemed unexpectedly cooler than I had remembered. And the Sun, impossibly, looked somewhat smaller than it had been prior to my arrival at the clinic.

Explanations came, but only as quickly as I could digest them.

“Something’s not right,” I said one evening as I shared a meal with Sterope. We had taken up a distantly romantic relationship since my awakening. I feared it wouldn’t last. Nothing inside the clinic’s austere corridors seemed real enough to transfer to the outside world, if I should ever rejoin it.

Her eyes roamed my face as if searching for recognition. Something like pain distorted her perfect mouth as she walked to the side of the small dining room and returned with a flatscreen, which she unfolded and placed in front of me.

“I want you to watch this,” she said.

So I watched, confusion giving way to silent amazement. The program showed a parallel existence that filled the gap in my memory. The footage had been recorded through Sterope’s eyes and ears. Her brain must conceal a wetwired vidcam, I thought dizzily, reconsidering her oddly mirrored eyes.

I realized that she was narrating as I watched, her hands folded on the table next to her abandoned meal. “You were sixty years old when you came to us,” she said, as if from a distance. “We uploaded you. We fell in love.”

I looked up from the screen, which showed my own face in the throes of orgasm. I recognized my apartment in the background, moodily lit by the bonfires from the street far below. “But I don’t remember . . .”

“This happened after you were uploaded. How could you? We assembled you from the data retrieved from space.”

“Space?” My sense of reality seemed to tilt, and I felt the stirrings of panic. Sterope continued narrating as I focused on the screen, watching this strange doppelganger continue on with my aborted life. I watched myself driven to a facility in the desert outside the city, where I relinquished my chip to a technician who tended towers of ill-defined equipment, his busy hands lit by a million flickering LEDs.

Sterope was there, of course, recording my image for posterity. I assumed she had a chip of her own. But when it came time to hand it over to the technicians (or whoever they were), she instead extracted a thin transparent cord from behind her ear. She gasped in evident pain (fear?) as she handed the pale green tendril to a tech standing guard next to a SQUID device of some sort.

“That worm-looking thing is an active upload substrate,” Sterope said from across the table. “A relatively untested technology. It records a user’s persona up till the moment of extraction.” She gestured for me to tilt the screen so she could get a better view. “Now watch. Sigmund is putting your upload chip into the SQUID on the table there, you see? In a few hours, it will have extracted all of the information from it and the computers will have translated it into a signal. It’s no coincidence this facility is adjacent to a radio telescope complex.”

“You transmitted it,” I said with the beginnings of understanding. “You shot it into space.”

She shook her head. “Not a place. A time. A moment. It feels like it happened a week ago, no?”

Suddenly I wasn’t sure I wanted to look at the screen anymore. I had the feeling the show was drawing to a discomfiting conclusion. “The uploading?”

“Yes. But you’re wrong. It hasn’t happened yet. You won’t be uploaded for sixty years. When your signal was sent, it was returned to us sixty years in the past. Now. The only reason I know as much is because of my professional connections with the Consortium.”

“You’re the Consortium? I thought they just made the arks.”

Sterope smiled wanly. “There are no arks. Even if there were, we couldn’t set sail in time to avoid being fried. The Sun’s growth rate is worse than you think.”

I closed my eyes and saw strange patterns. I had been staring at the screen for too long. My brand-new heart throbbed; I could feel it in my throat and head and gut. “Explain!” I shouted. “How did I get here?”

Sterope seemed to have anticipated my outburst. She leaned her elbows on the table and sighed comfortably, like an actress happening across familiar lines in a foreign script.

“Shortly after the Sun began to grow, an anomaly entered our solar system. At first we thought is was a chunk of dark matter. Or maybe a small black hole.” She shook her head. “None of the above. They scanned it with radar, laser. They dropped a probe into it to see how long it would broadcast until it got crushed. But they immediately noticed that they’d get their instruments and signals back before they had used them. So then they were forced to realize what they had. It was an Einstein-Rosen bridge. A time machine—but a very delicate and temperamental kind of time machine: an increase in its spin resulted in longer delays between the time when an object would appear in the past relative to entering the Bridge in the future—”

She seemed to lose herself for a moment. “Sixty years was the farthest it could send anything back,” she said slowly.

I leaned forward, my heart loud in my ears.

“We don’t know if the Bridge is a natural phenomenon or an artifact. Frankly, we don’t really care. There’s no time left to care.”

“The Consortium’s buying time,” I said, suddenly lucid. “There’s no time to escape so you digitize your clientele and send them back in time, put them in a new body . . .”

Sterope nodded vaguely. “Immortality is nothing to feel guilty about,” she said. Somehow her words seemed familiar. I looked at her smooth brown face, painted with white light from the flatscreen half-folded on the table between us.

“We can do this as long as we want,” she said. “The Bridge was discovered about sixty years before the year you were uploaded. So it must have been created—or formed—then. You can’t use a time machine to go back farther than the creation of the machine itself, obviously.”

“So it’s just now being discovered,” I said.

“That’s one way of looking at it.” She smiled. “I’d have to check the clinic’s records, but I don’t think you’re even born yet. Neither am I.”

“Causality violation? Paradoxes . . .?” I gestured emptily.

Sterope’s smile widened. “Maybe the universe splits in two every time we ‘violate’ something that ‘should’ have happened in the past. We don’t know. We don’t particularly care. The world’s still going to end.”

“But in sixty years I can shed this body and come back—”

“Barring accidents. You could still get run over by a truck. Your coolsuit could malfunction and you could drop dead from heatstroke.”

She got out of her chair and stretched. “The neural nets we installed are still taking hold,” she said, tapping my brow with a cool fingertip. “So you’re still in our ‘custody,’ so to speak.”

I followed her to the door, sifting through memories of events that hadn’t happened yet and probably wouldn’t.

Buying time. It’s all we could do.

The next morning I stood on the balcony of my temporary residence in the Consortium high-rise. Other clients had nodded when I had moved in, faces set in determined lines. I skipped breakfast and sat in a lawn chair, feeling naked behind the polarized quartz window.

The sky was a faint orange marred by palls of black smoke. The city sprawled below looked deceptively immutable beneath the vanishing stars, and I felt a tremor of fear begin to spread from the base of my spine.

I waited patiently for the Sun to break the horizon in a splash of portentous yellow-white, cauterizing and purifying as it grew, engulfing the brittle sky.

On the streets below, people had already begun to set themselves on fire.

About the Author

Mac Tonnies is a Kansas City, Missouri-based author/blogger enamored of esoterica. His second (and latest) book, “After the Martian Apocalypse,” was published by Paraview Pocket Books in 2004. Since then, he's ripped apart entrenched notions at UFO engagements in the US and Canada while continuing to post weird stuff (and chapters of his forthcoming book, “The Cryptoterrestrials”) on his blog, Posthuman Blues.